We are told by our parents and people who care about us to always adhere to our doctors’ advice even if the advice is to never procreate. The idea of having children for some women is a life goal and a natural part that makes a woman unique. Women who live in developed countries are encouraged to pursue a career and have a family. An ideal life for some women is healthy children, a loving spouse, and a successful career. Procreation is a right of any women to obtain and protect. Unfortunately, for some women with chronic illnesses, this organic act is life threatening. Some women with chronic illnesses such as severe diabetes, hereditary disorders, congenital ailments, and physical disabilities are therefore heavily cautioned from getting pregnant (Mahmud and Mazza).

Accordingly, even the potential threat of pregnancy can cause a woman to refrain from intercourse. Even if birth control is being utilized, there is always the chance that the form of protection is defective. The condom could tear, or the woman could be taking another medication that hinders the efficacy of their birth control. Additionally, many birth control devices and medications have hormones that can increase the tendency for a blood clout to form. Women with chronic illnesses thus need an emergency option. The morning after pill or emergency contraception pill is used ideally up to 72 hours and in some cases 120 hours after intercourse takes place (Rodrigues, et al). This pill is used if the woman’s contraception failed or if the woman did not use birth control due to oversight or rape.

In the United Sates, the morning after pill can be challenging to obtain depending on what state the woman lives in (Raymond, et al.). In certain states, a prescription is still required in order to buy the morning after pill. In other states, if the woman is below the age of 15, permission from a parent is necessary to purchase the emergency contraceptive pill.

In order to better understand the emergency pill, we should go through its history. The emergency contraceptive pill was first developed in France but has since then been made available in Albania, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, India, Israel, Morocco, Norway, Portugal, South Africa, Sweden, and the United Kingdom (Trussell and Wynn). Due to the sexual revolution in the 1960s, the “pill” was developed to thwart unwanted pregnancy, hence the concept of free love (Reich and Wolfe). As women became more empowered over their reproductive health, advancements in birth control have occurred. The various forms of contraceptives have grown in the last fifty years such as the intrauterine devices, the patch, intramuscular devices, and injections. All of these options are not foolproof and some are not covered by health insurance while others are not tolerated well by certain women (Harlap, et, al). The morning after pill is sold at pharmacies at an inexpensive price. In some states, pharmacists are able to dispense the morning after pill without a prescription. Most women are able to tolerate the medication without many side effects. So why are church officials and government personnel placing barriers for women, especially chronically ill women, from getting this much needed medication?

The Judo-Christian religion has a long-standing belief that any form of birth control is not accepted. They believe that any form of life is a blessing and to prevent this gift from being born is a sin. The morning after pill is not considered to have aborted abilities; however, it is still considered birth control. Some parents are concerned that the emergency pill may encourage young women to engage in sexual activity too soon. In the United States, there is a separation between Church and State. This separation is often in theory only. All of the founding fathers of the United States were from a Christian background and there are several references to God in many government documents. In the history of the United States, all of the presidents subscribe to being of a Christian religion. This religious belief is often reflected in America in terms of how the laws are formed and executed. Clinicians can refuse to prescribe or dispense birth control due to conscientious objection. Conscientious objection is a way to excuse healthcare providers from prescribing birth control, performing abortions, and dispensing birth control at the pharmacy due to a moral objection to impeding life from being formed (Fenton and Lomasky). The mere fact that there is an outlet for these healthcare providers not to fulfill their professional duties is an example of how Church and State can and do overlap.

To make matters more complex, there are certain assumptions that are associated with women with chronic illnesses. These assumptions are even more pronounced when the woman has a physical disability. Some individuals presume that women with physical limitations are not sexual beings. She does not have the same desires and needs of any other women. The idea that a woman with physical limitations may have sex is often a surprise to medical professionals (Chuang, et al). These healthcare providers may not see the need to offer birth control advice until it is too late (Perritt, et al). It is assumed that the woman is asexual and men do not find them attractive, hence healthcare providers do not see the need to counsel them on reproductive health (Perritt, et al). Women with chronic illnesses are often misinformed and they lack the ability to utilize resources in order to have a self-fulfilling life. For some with limited mobility, the morning after pill without a prescription is ideal while other woman with limited mobility may relay on a condom as their only source of birth control due to the risk of a blood clot and the male partner having easier access to condoms (Dragoman, et al). If the condom tears or leaks, the use of the emergency pill is vital.

Accessing the morning after pill should not be hindered by a prescription or judgment from religious leaders. The health of the woman is what is in question if she were to get pregnant. If the woman is sedentary, as the baby grows in the womb, the fetus can push against the diaphragm, which can interfere with her breathing. Also, if the woman is a diabetic, the trauma on the body by carrying the fetus to term may put the woman in a coma (Mahmud and Mazza). Avoiding pregnancy could prevent catastrophic medical circumstances and save thousands in medical costs. The emergency pill is a safe and effective way to avoid a costly and dangerous outcome.

Chronically ill women are faced with many challenges in order to have a healthy and fulfilling life. Being a sexual being is a natural part of any well-rounded existence. Most women accept the fact that there are consequences when engaging in sexual activity. They also have the right to easy access to manage their reproductive health. The morning after pill provides another resource for women that are often judged and/or overlooked.

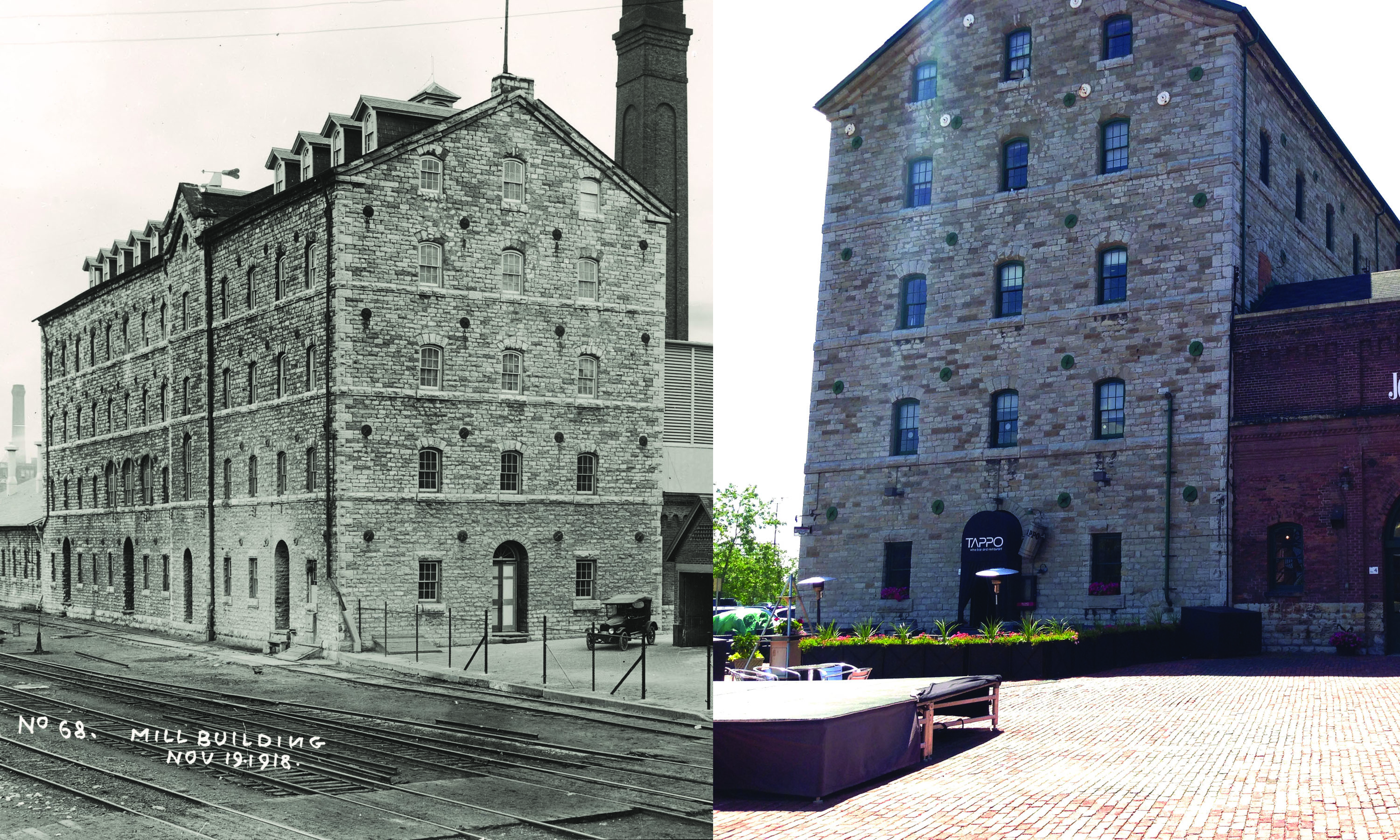

Cover photo by: Colin Campbell

** Editorial notes – Reference & Further reading:

Fenton, Elizabeth, and Loren Lomasky. “Dispensing with liberty: conscientious refusal and the “morning-after pill”.” Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 30.6 (2005): 579-592.

Campbell, Rebecca, and Deborah Bybee. “Emergency medical services for rape victims: detecting the cracks in service delivery.” Women’s health (Hillsdale, NJ) 3.2 (1996): 75-101.

Cramer, Joyce A., et al. “How often is medication taken as prescribed?: A novel assessment technique.” Jama 261.22 (1989): 3273-3277.

Creinin, Mitchell D. “Emergency Contraception: More Than A Morning After Pill.” Medscape women’s health 1.4 (1996): 1-1.

Rodrigues, Isabel, Fabienne Grou, and Jacques Joly. “Effectiveness of emergency contraceptive pills between 72 and 120 hours after unprotected sexual intercourse.” American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 184.4 (2001): 531-537.

Chuang, Cynthia H., Diana L. Velott, and Carol S. Weisman. “Exploring knowledge and attitudes related to pregnancy and preconception health in women with chronic medical conditions.” Maternal and child health journal 14.5 (2010): 713-719.

Raymond, Elizabeth G., James Trussell, and Chelsea B. Polis. “Population effect of increased access to emergency contraceptive pills: a systematic review.” Obstetrics & Gynecology 109.1 (2007): 181-188.

Harlap, Susan, Kathryn Kost, and Jacqueline Darroch Forrest. “Preventing pregnancy protecting health: a new look at birth control choices in the United States.” (1991).

Mahmud, Maimunah, and Danielle Mazza. “Preconception care of women with diabetes: a review of current guideline recommendations.” BMC women’s health 10.1 (2010): 5.

Holton, Sara, et al. “The childbearing concerns and related information needs and preferences of women of reproductive age with a chronic, noncommunicable health condition: a systematic review.” Women’s Health Issues 22.6 (2012): e541-e552.

Perritt, Jamila B., et al. “Contraception counseling, pregnancy intention and contraception use in women with medical problems: an analysis of data from the Maryland Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS).” Contraception 88.2 (2013): 263-268.

Dragoman, Monica, Anne Davis, and Erika Banks. “Contraceptive options for women with preexisting medical conditions.” Journal of Women’s Health 19.3 (2010): 575-580.

Lathrop, Eva, and Tara Jatlaoui. “Contraception for Women With Chronic Medical Conditions: An Evidence-based Approach.” Clinical obstetrics and gynecology 57.4 (2014): 674-681.

Trussell, James & Lisa Wynn. (2006, April 1, accessed 2006, April 26). “Dedicated Emergency Contraceptive Pills Worldwide.”

Reich, Wilhelm, and Theodore P. Wolfe. The sexual revolution: toward a self-regulating character structure. Macmillan, 1963.