Health illiteracy haunts the COVID-19 response in most of the Western democracies. Health illiteracy is defined as the inability to comprehend and use medical information that can affect access to and use of the health-care system. Conversely, health literacy refers to the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information needed to make appropriate health decisions. Low health literacy is more prevalent among older adults and minority populations.

Note that “health illiteracy” is not the same as the inability or ability to read, as Joseph Henrich points out in his seminal book “The WEIRDest people in the World” Just because one has been raised in a society that is Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic -WEIRD -, does not mean you support science over fiction or take the necessary actions to prevent virus transmission.

In the United States and much of Western Europe, the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in very high and unfortunate transmission rates and deaths with no end in sight in the next few months, as a third wave could follow on the (current) second wave. Once modern science is able to produce treatments and vaccines, it will still not mean “Mission Accomplished”. And we are assuming here that vaccine hesitancy – one of the major results of health illiteracy – can be overcome and that enough people accept to be vaccinated. Because even if this epidemic comes under control, another one sooner or later will appear.

The reason is simple: We live in our human world, blissfully unaware of what is going on in the animal world. Yet that is where most of our diseases come from. And that is certainly the case with COVID-19.

There is a link between this COVID-19 pandemic and bats. The vast majority of scientists who have studied the virus agree that it evolved naturally and crossed into humans from an animal species, most likely a bat. The culprit virus, SARS-COV-2, has a “zoonotic” animal origin and not an artificial one. The scientific clues to this reality lie in the genetic material and evolutionary history of the virus and understanding the ecology of the bats in question.

It is instructive to be aware that about 75 percent of new or emerging diseases originate in animals, and more than 60 percent of known infectious diseases in people such as rabies, ringworm, salmonella, and some other foodborne illnesses are transmitted from animals to humans.

Moreover, some recent One Health examples of challenging threats include coronaviruses like severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) along with reemergence of the likes of the Ebola virus and highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) viruses. Others are expected down the road as we saw with COVID-19.

Indeed, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) website highlights the overall ineffectiveness of public health officials in dealing with many health issues such as combatting the raging COVID-19 pandemic and the “anti-vaxxer movement” whose members do not accept preventive vaccinations, at great risk, not just to themselves but to family members and others.

What have such educated and scientifically advanced societies been missing, or leastways, why have they failed to build on approaches that have been advocated for decades, yet never taken up to the extent that the spread of the virus comes under control?

Sadly, in the real world, people who literally know almost nothing about complex health subjects righteously and boldly ignore or belittle those who have devoted their lives to studying and obtaining credentials that substantiate their areas of expertise in scientific and other endeavors.

Thomas M. Nichols superbly analyzes the problem in his 2017 book, ‘The Death of Expertise: The Campaign against Established Knowledge and Why it Matters’. Nichols is a recognized authority in international affairs, an academic specialist who currently serves as a professor at the U.S. Naval War College. He explains how digital technology – such as being able to “Google” any subject – has led many reasonably well-educated individuals into believing they know more than accredited physicians, veterinarians, climatologists, military-trained generals, legal scholars (lawyers), and others.

This enhanced form of ignorance hinders such individuals and their many followers on social media from seeking and understanding issues needed to solve complicated problems.

Arguably, Facebook, Twitter, and especially YouTube sustain the spread of this type of behavior to millions of people. A recent study of Facebook posts across Europe, carried out by the Digital risk analysis firm CounterAction, found that since promising candidate vaccines were announced, the volume of Facebook posts carrying reckless disinformation about the vaccines and other issues has increased in all EU languages. For example, allegations that vaccines cause “genocide” or cancer along with a number of wild conspiracy theories were found in some 30,000 Facebook posts in Germany alone. This is a matter of concern, considering that 2 million Germans follow such Facebook authors.

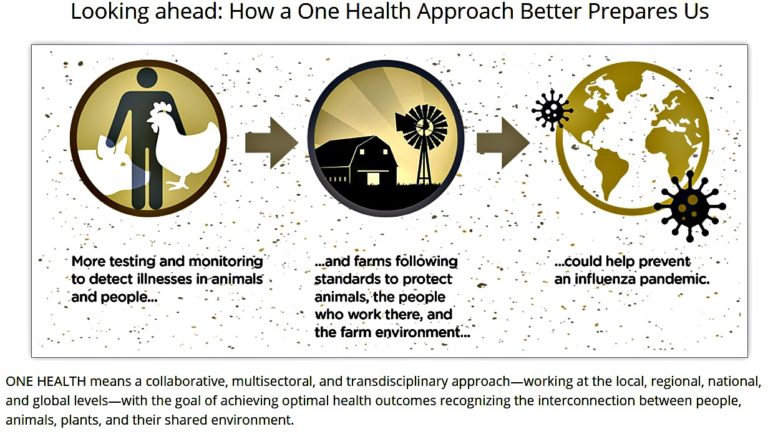

This brings us to how to deal with so-called silent and often hidden epidemics – silent and hidden in the sense that they are not understood or seen as threats by a very large number of persons – that can so quickly devastate hundreds of thousands or potentially millions of lives. It means recognizing the interaction of multiple disciplines, namely those that directly or indirectly affect the interaction of animal, human, and environmental health factors, namely a “One Health” approach. Indeed the U.S. CDC also has a separate One Health webpage.

One Health leaders worldwide have presented cogent arguments for incorporating the One Health approach, highlighting the factors of zoonotic diseases, i.e. transmissions from animals to humans. They have also provided procedural methodologies for political leaders. In practice, this means that public health agencies could systematically include the health and surveillance of domestic animals and wildlife at the point where human and veterinary medicine interface.

In anticipation of other emerging or re-emerging threats like the Nipah virus, visionary biopharmaceutical companies with a strong One Health orientation are working diligently to develop efficacious, safe vaccines. Dr. D. Gray Heppner, Crozet’s Chief Medical Officer said: “Nipah virus infection causes a dreadful disease for which there is no treatment…” The disease has a 40 to 75% mortality rate, one which will require a public/private partnership to deal with effectively.

Over the past two decades, numerous professional journals, books, scientific publications, and news media reports have been posted about One Health, referencing the One Health Initiative, One Health Commission, and other websites. These reliable sources have described critical guidance for global, regional, national, state, and local elected officials as to what and how to follow sound, proven scientific advice from public health/medical experts when drafting policy in crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Established epidemic mitigation modalities have been expressed repeatedly by public health professionals, i.e. wearing masks, social distancing, hand washing, adequate testing, contact tracing, and avoiding premature public openings of various facilities like restaurants, bars, schools, theatres, and sporting events. All sensible public health authorities today voice similar caveats.

Often in the past, the United States has shown scientific, political, and funding leadership in efforts to control and/or contain public health epidemics, opting for a science-based approach.

One can go back to the building of the Panama Canal and measures taken by the United States in 1904 to eradicate the mosquitoes Aedes aegypti and Anopheles, the carriers of yellow fever and malaria, respectively, from the canal zone, as a case in point.

Regrettably in these last few years that has not been the case with the exception of the Obama Administration’s response to the Ebola crisis in 2014, with subsequent approval of $5.4 billion in additional funding for international and domestic efforts, including research and development.

At that time the Ebola coordinator was Ron Klain who has just been selected by President-Elect Joe. R Biden to be his Chief of Staff, a promising sign that health security will be recognized as a priority in the new Administration.

The Federal government has not performed as it had in much of the past with a nationwide strategy. With COVID-19, individual States such as Florida, Georgia, Texas, and the Dakotas have abandoned prudence, taking on anti-science agendas vis-à-vis life-preserving COVID-19 measures. They opted to embrace Presidential pronouncements supporting opening social gatherings and enterprises far too soon, to achieve short-term economic gains.

For them, epidemiological expertise, i.e. the science of public health, the backbone of disease control, was no longer the trusted guardian of the “people’s health.” Discrediting tactics have been resorted to by the “People’s House” (known as The White House), to undermine highly respected leading scientific authorities (with impeccable credentials) such as physician Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, a national and international treasure, who indeed, endorses utilizing the One Health concept.

In the United States, and worldwide, we appear to be at the dawn of a potentially more promising era. One in which most Americans and its future government appear to recognize it can no longer afford to ignore or be penny-pinching about the prospects of silent epidemics (or pandemics) and must take on full bore, a One Health approach.

What does One Health mean for the United States? At the Federal level, the critical agencies and institutes must be given the authorities, resources, staff and seats at the highest decision-making tables to tackle known and unknown challenges to provide integrated, coherent, and multi-disciplinary proactive responses.

On a global level, it will require the United States, not just to rejoin the World Health Organization (WHO), but also become a more active, engaged, and substantially bigger funder of the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), a lesser-known international body to fight animal diseases at a global level that was created as the Office International des Epizooties (OIE) through an international Agreement signed on January 25th, 1924. In May 2003 the Office became the World Organisation for Animal Health but kept its historical acronym OIE. The OIE has done extraordinarily professional and important work in assessing possible zoonotic diseases with relatively limited resources. And there is also a need to support the work of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), a longtime WHO collaborator on matters of nutritional health and animal science and advice, as another crucial partner in the effort.

If we are all going to get ahead of future “Silent Epidemics”, it must be done with the active and sustained collaboration of veterinarians, physicians, environment specialists and other health scientists—in short, we all need a One Health approach, and now is the right time to make it happen.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. Featured Image: Girl with Goat, Davis Farm and MegaMaze, Sterling, Credit: Davis Farmland (Massachusetts, U.S.)