China is blamed for attracting developing nations and taking cash from them for economic ventures and later politically controlling them if they fail to return that money to China in time. China is also blamed for FDI (Foreign Direct Investments) in developed countries, notably with an agreement recently signed with Italy. This article explores how China’s investments are deployed in the developing world and what it means for the future of countries indebted to China.

A first observation is in order: It is a fact that in numerous developing nations, a significant part of the crushing obligation or debt is owed to a single source, China.

As indicated by an investigation by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), from 2013 to 2016, China’s benefaction to the people’s debt of intensely obligated helpless nations, multiplied from 6.2 percent to 11.6 percent.

China’s loaning has grown considerably through the Belt and Road Initiatives (BRI). Taking note of an absence of financial attainability of some BRI projects, numerous onlookers speculate that the activity is mostly spurred by China’s desire to stimulate its economy, get vital resources, and convert its monetary access into a key political presence in the BRI recipient countries.

China has invested billions of dollars into ventures abroad, assisting the economies of numerous countries over the globe, including South Africa, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and many others.

The debt that these countries contracted with China gave them monetary liquidity and they saw this as a needed lift to become noteworthy players on the worldwide stage. Be that as it may, these nations have all experienced financial difficulties when the time came to pay back the debt. The major reason is that the loan conditions are very tough to meet.

BRI loans foresee that the recipient nation has to surrender an enormous stake in its economic framework, including ports and trade routes. This technique of trouncing or conquering is famously known as “debt-trap diplomacy”. Here are a couple of examples illustrating how it works – keeping in mind that the same model is followed everywhere, from Asia to Africa.

Case Study in Debt-trap Diplomacy: Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka is regularly depicted as a nation that fell into a Chinese debt trap because of the many public ventures financed by China.

One such venture was Hambantota port, which was rented to China Merchant Port Holdings Limited (CM Port) for $1.12 billion in 2017. This venture is to a great extent the only explanation as to why Sri Lanka is broadly referred to as a noticeable example of getting caught in Chinese obligations and being compelled to hand over national resources with vital significance to China.

The general conviction, by all accounts, is that Sri Lanka wasn’t able to pay the loan it got from China to build Hambantota port: There was no way out but to hand over the port to Chinese control.

Case Study in Debt-trap Diplomacy: Indonesia

In 2003, Suramadu Bridge was designed and developed by a consortium of Indonesian organizations working with Chinese companies, the China Road and Bridge Corporation and China Harbor Engineering Co. Ltd. The total cost of the task, including access to the bridge, has been estimated at US$445 million.

In 2007, the coal-fired 990 MW Indramayu West Java 1 force plant was agreed to and development started in 2007. The plant, opened in 2011, was operated by a consortium of temporary workers: China National Machinery Industry Corporation, China National Electric Equipment Corporation. Assessed cost: $870 million.

Additional Chinese investments include:

- In 2011, the Sumatra coal railroad, at an evaluated cost of US$1.5 billion.

- In 2015, Jakarta-Bandung fast rail, at an evaluated cost of about US$5.5 billion.

- In 2015, Central Kalimantan Puruk Cahu-Bangkuang coal railroad, at an evaluated cost of US$3.3 billion.

In April 2018, Indonesia and China signed five agreements worth a total of $23.3 billion, including some activities designed to switch over to more renewable and cleaner energy sources, for example, investing in hydropower plants and changing over coal into dimethyl ether, among others.

In March 2019, Indonesia and China agreed to a plan worth US$91.1 billion for 28 national activities under the BRI banner, as emerged from the main gathering of the Joint Steering Committee for the Construction of Regional Comprehensive Economic Corridors for Cooperation between the nations held in Bali.

Next Ground for Chinese Debt Trap Diplomacy? The Middle-East

A new chapter in BRI expansion is likely to open: The Middle East.

We are all aware of the Lebanon economic crisis. Recently, Hezbollah’s pioneer Hassan Nasrallah asserted in mid-June that China was prepared to put billions into Lebanon’s economy.

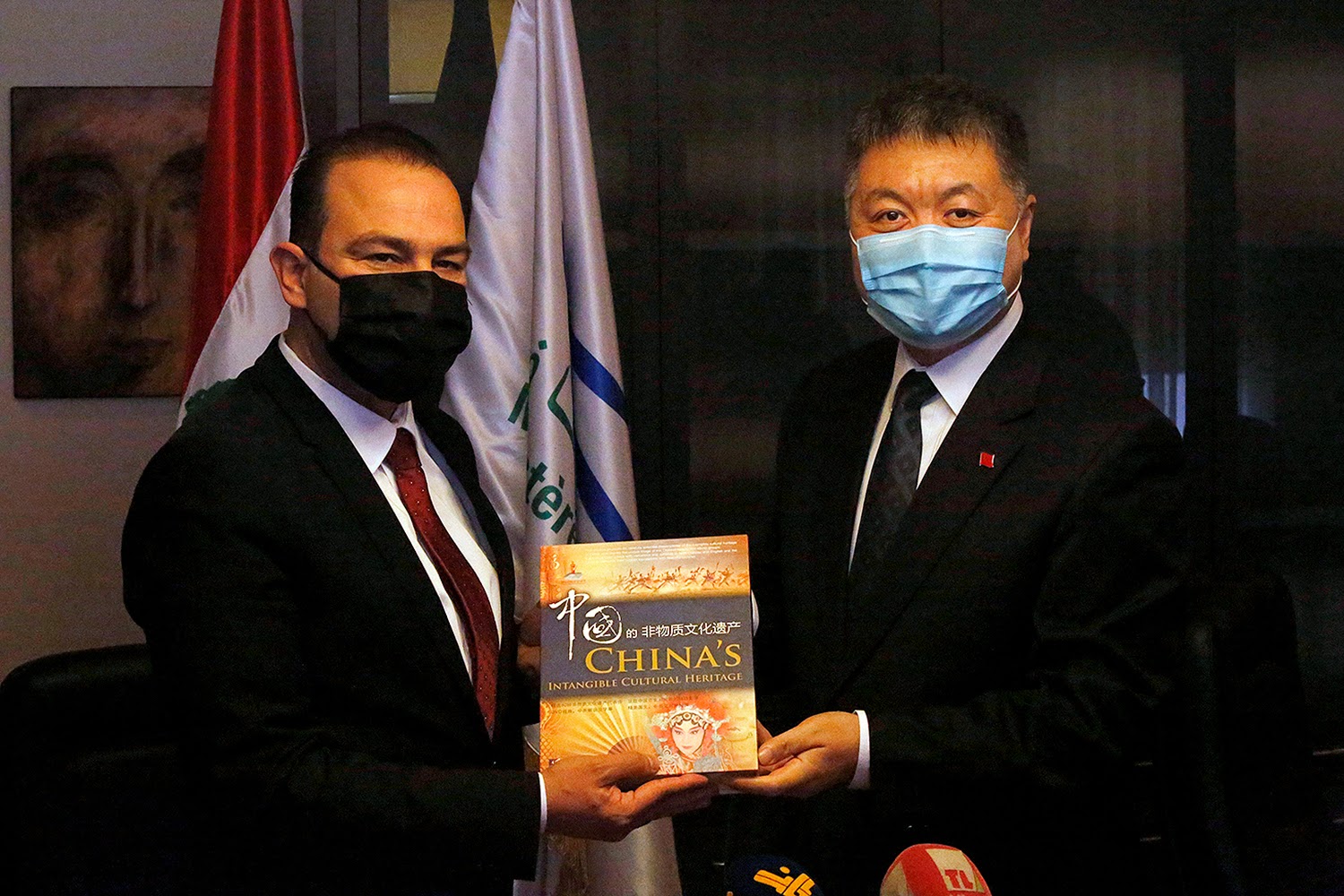

A gathering on June 30 between a Chinese delegacy and the Lebanese prime minister, alongside the ministers of various industries including public works and transport, energy and water, and tourism, additionally fed expectations that China may be prepared to invest in Lebanon and make the country a major element in its Belt and Road Initiative.

On the other hand, Xinchun Niu, who is the director of Middle East studies at China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations (CICIR) said and Norvergence quotes: China-Middle East countries do not follow a “political-strategic logic”, insisting “it’s an economic logic”.

It would appear that for China, the Middle East remains on the distant back burner of China’s strategic global strategies.

COVID-19 combined with the oil price crisis could dramatically change the Middle East. And this could also change China’s investment plans in the Middle East. However, the good economic times of China and the Middle East are already in the past: Both China and the Middle Eastern economies have been slowing down. In the future, it is likely that the pandemic combined with the oil price problem will make the Middle East situation worse.

So, expect China’s economic relationship with the Middle East to be deeply affected.