Updated 10 June. Two political developments threaten Europe: A no-deal Brexit that would certainly hurt the British economy but would also be painful on the continent, and an out-of-control deficit in Italy. Taken separately, Europe could handle the issues. But the problem is that they come together.

The power of Eurosceptic politicians is definitely on the increase across Europe. It has always been so in the Visegrad group of countries (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia) where populists are firmly in government, running increasingly “illiberal democracies”. Hungary’s battle against philanthropist George Soros is a good illustration of what is wrong in those countries.

Yet the threat to Europe seems relatively minor. After all, those countries were always on the periphery of Europe. They were latecomers to the European Union and, because of the Soviet legacy, it surprises no one that the bulk of their population is apparently not attached to democratic values.

What is new is that traditionally liberal West European democracies are now also following in the populist footsteps of Visegrad countries. It first happened in the UK with the June 2016 decision to leave the EU.

The Brexit referendum was astonishingly mismanaged from the start with no requirement to ensure that a real majority had voted Brexit (they hadn’t) and no control over fake news (notably over supposed migrant invasions or Boris Johnson’s famously false promise of regaining £350 million pounds from Brussels).

Yet Conservatives ignored the democratic failures of that referendum and were quick to jump on the bandwagon of Brexit, claiming that it was the sacrosanct “will of the people” and had to be honoured at all costs.

Since June 2018, the UK is no longer alone on that path. Italy joined it when two populist politicians, Di Maio, the Five Star Movement leader and Salvini, the Lega leader came together to form a government. The alliance looked fragile from the start, the two are unlikely bedfellows.

The Five Star Movement is a leftist populism colored by some socialist fantasies (like the Reddito di Cittadinanza, citizens’ income). The Lega is extreme right, with neo-Nazi tendencies – but the government is holding up surprisingly well, even though the balance of power has totally shifted, putting Salvini firmly in the driver seat. Not only did Salvini win a hefty 34% at the European parliament elections in May, but the latest polls in June show he’s ahead by another two points, around 36% against Di Maio’s paltry 16%, a further one percent drop.

Let’s take a closer look at what is happening in the UK and Italy, the two major battlegrounds where the future of Europe is now being played.

The UK: A Future American Colony?

In the UK, Boris Johnson appears now as the most likely candidate to succeed May as Prime Minister and in his speech to the Commons, he has made it very clear that he is committed to a no-deal Brexit. And to “hard negotiations”, promising not to pay the UK’s due to the EU and simply leave – following thus the suggestion made by Trump during his visit to the UK. Is Johnson Trump’s new poodle?

Indeed. A no-deal Brexit has suddenly become palatable, even desirable, thanks to Trump. It’s worth going over what Trump did in the course of his just-completed three-day visit to the UK. A notorious foe of the European Union, he gleefully added fuel to the fire.

Apart from uselessly insulting the Mayor of London and showing himself once more the clueless bully that he is, Trump was crystal clear from the get-go: Prepare for a no-deal Brexit, he said, and send in Farage in the UK-EU negotiations. Farage, his personal friend since the days of his own 2016 campaign for President. Farage, the Eurosceptic politician who has just led the Brexit Party to victory in the European Parliament elections, winning 32% of the votes. Stunning for a party that was launched just six weeks ago (incidentally, without Farage’s help, he joined as its leader only once it was set up).

At the end of his visit, Trump added a juicy cherry on the cake: He offered a post-Brexit US-UK free trade deal where “everything is on the table” — including the National Health Service.

That last bit proved to be a false step, provoking outrage among the Brits who love their NHS and were appalled at the vision of American Big Pharma taking it over (the NHS is the UK’s biggest purchaser of medicines and medical equipment).

Trump quickly backtracked but the trade deal offer remained. A big boost to Boris Johnson and all the extremist Tories that want a no-deal Brexit.

A new trade deal with the US is not likely to solve any economic problems caused by crashing out of the EU without a deal in place. And it is certainly not attractive to those British consumers who fret that the market will be flooded with American food produced to lower environmental and animal welfare standards, such as chlorine-washed chicken. But beyond that, there are deeper reasons why a UK-US trade deal is problematic.

First, US-UK economic ties are doing very well already, they are “deep and enduring”. The UK is the United States’ 7th largest trading partner. Still, even if that sounds good, we need to realize that the UK is a midget on the American economic scene: According to 2018 American government estimates, U.S. exports to United Kingdom accounted for merely 4.0% of overall U.S. exports and the U.S. goods trade surplus with the UK was $5.4 billion – a nice sum but nothing remarkable.

This suggests that there’s not much room for further expansion. Incidentally, that is to be expected: International trade has been doing very well with globalization over the past three decades, and trade between two partners like the US and the UK who’ve known each other forever and speak the same language is already at the top. So how much room is there to replace UK-EU trade (and investment) cut off by Brexit?

To gauge that, we have to remember that transport costs are not a fantasy. Supply chains go easily over the Channel, not so over the Atlantic. A trade deal with the United States is not the same thing as the free trade deal the UK has now with the EU. Small wonder that the EU remains the UK’s main trading partner, by far. The numbers tell the story: about 57% of exports and 66% of imports (2016 data) is with the EU or countries the EU has trade agreements with.

To summarize: There is no question that the US is economically important for the UK, but the problem is that the UK matters a lot less to the US. A trade deal with the U.S. can never replace the trade lost by leaving the EU with no deal Brexit.

Moreover, a trade deal brokered by Trump is fraught with danger. He declared a trade war on Mexico even though a new trade deal to replace NAFTA had been agreed to and signed just six months ago. Ten days later he appeared to walk it back when Mexico caved in and agreed to an immigration deal forcing it to stop migrants passing through on their way to the US. But on 10 June, the fight was still not over, as Trump threatened more tariffs on Mexico in a dispute over another portion of the immigration deal.

It is obvious that for Trump trade is a weapon to beat partners into line and force them to follow his command. In short, Trump is not a trustworthy partner as an article in the Economist pointed out: “Allies looking for new trade deals with America, including post-Brexit Britain, will worry that a presidential tweet could scupper it after it has been signed.”

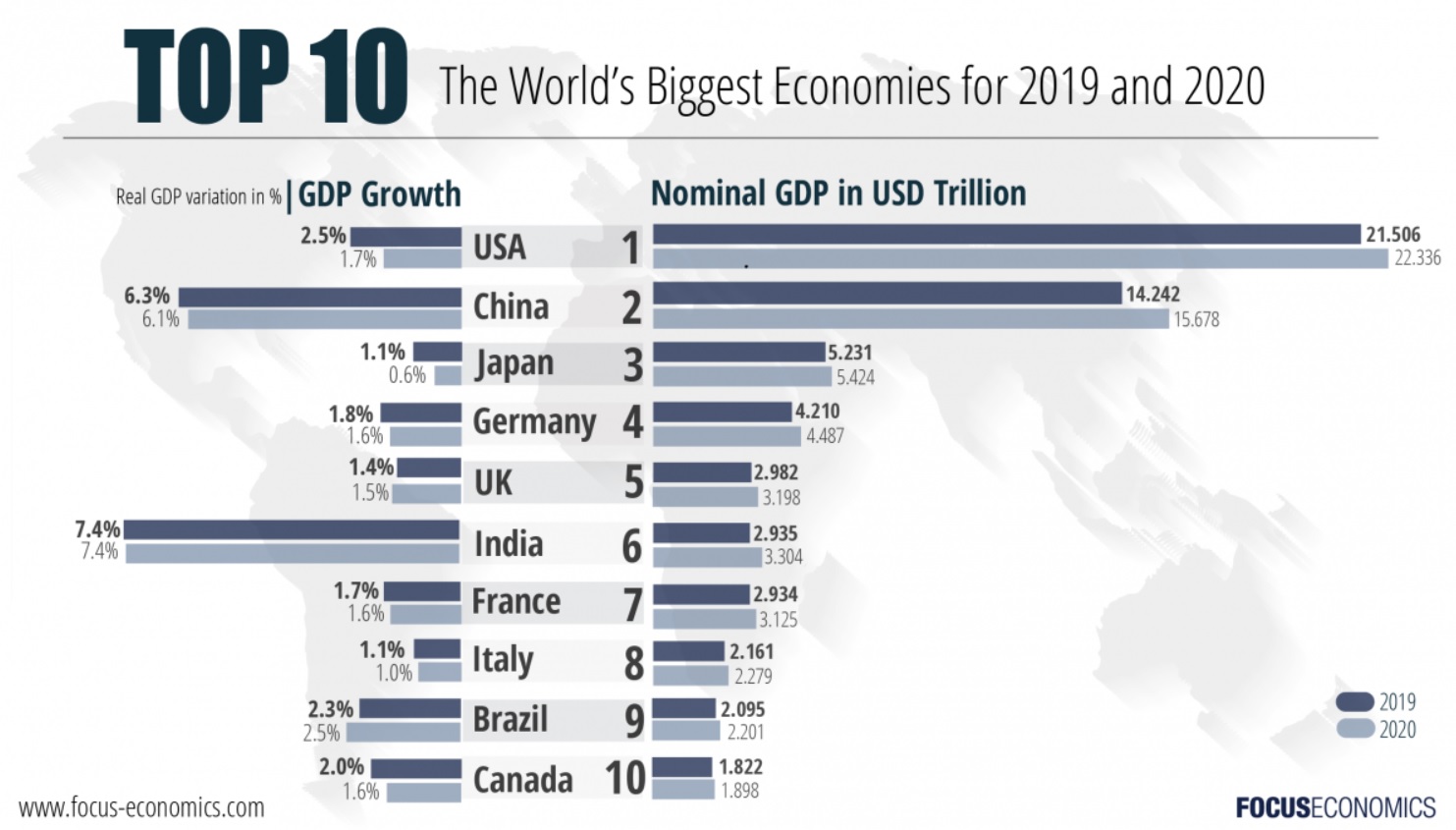

Not only that, but there’s a real risk that the UK, a small country compared to the American colossus – 66 million people vs. 327 million – will have to agree to any conditions put forward by the Americans. In effect, becoming a minor trading partner. And if it does not toe the American line, it will be threatened with tariffs or quotas. Because Trumpìs agenda is America First. And the UK? An American colony in Europe. In American eyes, a small country, a country that, worldwide, is barely ahead of India and well behind Germany.

If the British public realized what the ranking of their country really means politically, I believe they would not be so keen to leave the EU. Belonging to the EU is the best defense for mid-sized European countries like the UK against mega-powers like the US or China. Because the UK, from an economic standpoint, is a small player: China is five times larger, and the U.S. is seven times larger.

Go explain that to the Tories. Or to Corbyn, the Eurosceptic Labour leader who is so enamoured of the idea of leaving the EU that, in spite of the extraordinary poor show of Labour at the European parliament elections, he is still not drawing the obvious conclusions. A new referendum. That is what Labour should call for but won’t, because of Corbyn’s personal attachment to Brexit – even if it goes against the interests of the British working class.

Italy: Falling Out of Europe, a Rogue State?

Things are not much better in Italy. Three days ago, an incomplete draft of the letter from the European Commission was leaked to the press complicating negotiations with Brussels. The letter, finally made public on June 6, warned that unless Italy changed course and reigned in its growing budget deficit, the European Commission would take legal action. In a formal debt procedure, Italy could face serious financial penalties, up to €3.5 billion.

Italy’s public deficit is the highest in the EU, over 132 percent of gross domestic product and rising, far above eurozone guidelines of 60 percent. Italy, expected to run a budget deficit at 2.5% of GDP this year (something Brussels has agreed to), plans to raise it to more than 3% next year, which is contrary to European guidelines.

Italy is not the only country to do so – France is another culprit, as it had to recently spend more to respond to the Yellow Vests protests.

But the case of Italy is different.

In the face of a widening structural deficit (the underlying deficit excluding interest payments) and decades-long stagnation, the government, instead of reviving the economy with business-friendly policies and job creation, is engaged in a series of populist spendthrift vote-getting policies.

Two pet policies of the Five Star Movement have already been (partly) implemented: “Quota 100” (allowing people to take early retirement) and “Redditto di cittadinanza” (citizens income, a monthly cash gift to selected poor – over 500,000 Italians have been enrolled in the program so far). Now it’s Salvini’s turn with the “flat tax” (an income tax cut across the board to a “flat” 15% level).

Salvini, the real leader of the government, was quick to react to Brussels, maintaining he would go forward with his “flat tax” – even if it meant going against European rules. He blamed cuts, sanctions and austerity for Italy’s debt and unemployment. “We have to do the opposite,” he said. “We don’t want anyone’s money. We only want to invest in work, growth, research and infrastructure. I am certain that Brussels will respect this will.”

Brussels is unlikely to appreciate. What concerns investors and most observers about this whole situation is the impact on the Euro. The prospect of an Italian default is terrifying. It’s the Greek Euro crisis multiplied by ten. Salvini, deep down, is probably happy, he always wanted to take Italy out of the Euro, and now he may well be close to achieving that objective.

It is stunning to see how irresponsible both Salvini and his partner Di Maio are. They even recently suggested instituting a form of payments parallel to the Euro with short-term government bonds, known as “mini-bots”. The original proposal is the Lega’s and the fact that both government leaders have recently revived this proposal has caused Moody’s to react, blasting it as “credit negative”.

The markets, predictably, liked none of this. The infamous “spread” (the difference between Italian and German government bonds) has widened again to dangerous levels, curbing in practice the government’s ability to raise the funds it needs to function.

The problem is that Salvini’s intentions may sound good (they certainly appeal to his fans), but there are no policies to support what he says. The flat tax, which is a Trump-like gift to the rich, won’t cut it. Another one of this pet projects, the planned TAV (high speed train connecting Lyon, France to Turin, Italy) will help part of Northern Italy’s economy but much more is needed for the whole country. Something like a comprehensive structural reform (to address corruption and red tape) and an investment plan (to relaunch the economy). But none is in sight.

Moreover, to complicate matters, Salvini’s partner in government, Di Maio, is dead set against both his proposals, the flat tax and TAV.

The question on everyone’s mind in Italy now is: When will the government fall?

Some people (for example in the PD) are getting ready for elections in September or October. Many expect that Salvini, riding on his success at the European elections and taking advantage of the collapse of the Five Star Movement (down to half its former level), will go for it.

But Salvini may hesitate. The Italian electorate is notoriously fickle and volatile. The PD leader Matteo Renzi’s fall from grace in just four years must haunt him. In 2014, Renzi won 40% of the votes at the European Parliament elections, he was the most successful political leader in Europe. In 2016, he lost a referendum to reform the Italian political system and was kicked out of government. Today, he’s a forgotten senator from Florence.

It is likely that Salvini will remain where he is as long as possible, taking advantage of Di Maio’s weakness to push forward his own agenda. But his problem with Brussels won’t go away. On the contrary. His very success with Eurosceptic populists means that Italy has been pushed out of the European control room.

Today, as I write, the three main European groups at the European Parliament, EPP, ALDE and S&D, are holding a sort of informal “mini-summit” to agree on a candidate for the European Commission, to be presented to the next European Council. All EU members are participating in the talks except three countries (not represented in those groups): the UK, Poland and Italy.

Unquestionably, Italy’s vote for Eurosceptic parties has pushed it out of the European game. What a change for Italy. Up to now, Italy had been ever so present in Europe. Currently, it is heading the European Central Bank (Mario Draghi); presiding over the European Parliament (Tajani); running foreign affairs (Mogherini). It is said Salvini would settle for having one of the more important Commissioner posts, either competition or agriculture. Good luck with that.

Italy is turning into the unthinkable: A rogue European state.

But if Italy does exit the Euro, it will be a major catastrophe for Italy. For Europe too because Italy is the EU’s 4th largest economy (after Germany, France and the UK). And for the whole world, because Europe as a whole, the 28 countries of the EU, is still the world’s major trading partner.

Again, an unthinkable outcome.