The Right to Health is guaranteed under Article 25 of the UDHR and in other regional human rights instruments, statutes, conventions as well as in the national constitutions of many African countries. However, there seems to be a lack of political will and commitment on the part of African governments to guarantee and safeguard the Right to Health among its populace. This appears to occur in stark contrast to the human rights movement which stipulates that access to good health and well-being is a human rights issue that the state as a duty-bearer must fulfill. There are many questions in the offing, regarding why most African leaders –including in Zimbabwe – do not give due consideration to safeguarding the Right to Health. Whilst it is easier to hide behind the issue of inadequate financial resources, we can see that most African and Asian countries receive huge donor funding, as well as bi-lateral and multi-lateral support earmarked towards the fulfillment of the Right to Health, which is broadly construed. Again, the very same governments have resources that are channeled elsewhere and very often not toward the health sector. This then begs the question whether such countries are truly committed to realizing and achieving SDG number 3, which is to:

“Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages”

In explaining such, it is illustrative to use the case of Zimbabwe.

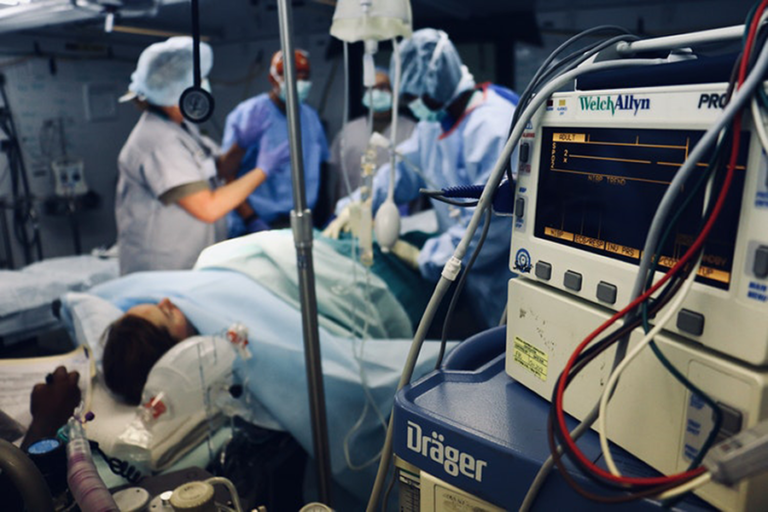

Notwithstanding the fact that Zimbabwe is a state party to numerous treaty bodies, covenants, conventions, and statutes that guarantee the Right to Health, the situation on the ground indicates lack of commitment in making this right a reality rather than a mere aspiration. The Zimbabwe Constitution adopted in 2013 under section 76 guarantees the Right to Health to its citizens. Again, under regional human rights instruments, which Zimbabwe is party to, the Right to Health is also underscored. Zimbabwe is a signatory and state party to the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights (ACHPR) wherein article 16 expresses the Right to Health. Furthermore, the country also signed and ratified the CEDAW Convention which provides for sweeping rights to women, including the provision of adequate and quality maternal health services. But looking at the shortage of basic equipment in the maternal clinics and hospitals in Zimbabwe, this right is far from being realised.

Taken together, these statutes and instruments bound the Zimbabwean government to make necessary steps and measures to guarantee access to affordable and quality health care. However, this does not seem to be the case, and it can be illustrated by a few examples. Since the beginning of the Zimbabwean Crisis, which started in the early 2000s and continues to date, the health sector has been collapsing. This is evident in the quality of health care services, in which shortages of medical utensils, namely bandages, syringes, gloves, and needles as well as manpower are commonplace. The few doctors who are manning government clinics and hospitals are frequently overwhelmed, demonstrated by the high patient-doctor ratio. In most cases, few patients can afford to see a doctor, as most doctors have gone into private practices, which charge exorbitant fees. But there is an explanation as to why the country is in such a deplorable state of affairs and why the government is failing to provide for the Right to Health in line with SDG number 3.

As it seems to be the trend in much of Africa, Zimbabwe puts much of its budgetary allocation toward other sectors and therefore not the health sector. This occurs in stark contrast to the aspirations of the Abuja Declaration, which states that African states must commit at least 15% of budgetary allocation to the health sector. In Zimbabwe, during Mugabe’s reign and following his demise in what came to be known as a military-assisted transition, the continued dismissal of the health sector in terms of budgetary allocation has become the norm rather than the exception. In this regard, huge sections of the national budget have been channeled into other non-essential sectors, such as the security sector. This demonstrates a regime more inclined to entrench state security as opposed to human security. In 2018, the Ministry of Health and Child Welfare allocated US$473.9 million, 68.1% higher than the sum of US$281.98 million that was allocated in 2017; however, this is still too little. Following intense lobbying from Zimbabwean parliamentarians, the allocation to the health sector was boosted with an additional US$65 million. But again, this is still far from meeting the high health costs, especially in countries like Zimbabwe where HIV and AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis (TB) and other communicable diseases including typhoid and cholera are still rampant.

As a corollary, we have seen the donor community and multi-lateral agencies chipping in to fill in the gap where the government has failed to provide adequate health care, but this is only part of the story. The Zimbabwean government’s failure to protect, promote and fulfill the Right to Health in line with SDG number 3 can be expressed as the lack of political will rather than lack of resources. Zimbabwe is a country that boasts of natural resource wealth – including diamonds, manganese, gold, platinum, zinc, cobalt, tin, coal, asbestos and nickel amongst other minerals. In contrast to this opulence, little has been done to improve service delivery in hospitals. A common sight in most–if not all government hospitals in Zimbabwe–is that of obsolete medical equipment. In addition, there are also severe shortages of dialysis machines for renal patients.

To complicate the already precarious health situation in Zimbabwe, most rural clinics do not have ambulances, with only one ambulance to be found at district hospitals. In most cases, such an ambulance is expected to service a constituency of circa 28,000 villagers. The situation in urban areas also mirrors that of rural areas, where there has been a prevalent shortage of drugs, the only difference being that in the former, there are private pharmacies where drugs are sold in the US dollars. Clearly, there is a world of difference between availability and affordability of medicinal drugs. The sad reality in the Zimbabwean context is that the prices are beyond the reach of many ordinary citizens, especially in light of the liquidity crunch currently facing the country. Access to basic health care has become an illusion for many, as opposed to a human rights issue. It is therefore unsurprising that the deplorable state of government hospitals across the country has spurred the mortality rate (infant and maternal). This burden has been increasingly felt by poor citizens who cannot afford the exorbitant fees charged by private hospitals. The state of the Zimbabwean health sector is the profligacy of the political elites. This is evidenced by government expenditures put toward buying cars for the ruling party and other top officials at the expense of buying hospital equipment, drugs and meeting the welfare of health professionals.

For a few years now, the health practitioners, nurses and junior doctors have been involved in industrial job actions. The major grievances spurring the strikes were concerns over the poor working conditions and poor remuneration. In April 2018, the Zimbabwean government acted in a lethal manner by dismissing all the striking nurses, but it was the ordinary citizens (patients) who had to bear the brunt of such an impulsive and ill-informed decision. This again came at a heavy price especially for those suffering from chronic illnesses. Some even lost their loved ones. This is contrary to the Right to Health and the Right to Life as enshrined under (inter)national and regional human rights instruments, statutes, covenant, and conventions. If left unchecked, the Zimbabwean government’s enduring neglect of the health sector will continue to stymie other well-meaning efforts towards the realization of SDG 3.

The fact that Zimbabwean political leaders fly to receive medical attention elsewhere in neighboring countries such as South Africa is a testament to their lack of confidence within their own health institutions. It will therefore be difficult for them to commit to improving and reforming the state of health facilities in Zimbabwe. However, this is not particular to Zimbabwe, but most African countries. There have been many sitting African presidents who passed away whilst receiving health attention in other countries, but not their own. The case of Michael Sata, former Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi, Omar Bongo, and Levy Mwanawasa are quite telling, all of whom died whilst receiving medical attention abroad. Even sitting incumbents or former presidents loathe receiving health care in their own homeland.

RELATED ARTICLES:

![]()

Moving Outside of Policy Pigeonholes to Improve Global Health

![]()

Sustainable Energy Can Power A Health Revolution

![]()

Global Health Systems: Ready for the Next Pandemic?

The case of Mugabe who used to fly routinely for medical check-ups in Singapore and Malaysia is before all of us to see. So is the case of former Angolan President Jose Eduardo dos Santos, who used to frequent Spain for medical health checkups during his tenure. This is all proof of African leaders’ neglect and disdain of their own local health facilities. It is such behavior that discourages African leaders from improving the health facilities in their own respective countries. There is a strong reason to believe that unless the Zimbabwean government commits itself to protect, promote and fulfill the Right to Health by taking positive steps to improve the health sector, the realization of SDG 3 will remain a yearning out of reach of ordinary Zimbabweans. In light of such a disconcerting trend, this is the time to commit to realizing SDG number 3 in African countries.

To sum up, the Right to Health and SDG number 3 speaks to the deeper and wider issues regarding the prevailing mis-governance and poor health policies present in much of Africa. That said, all that is needed now more than ever is real action beyond summit talks, rally speeches, sloganeering and newspaper headlines to propel forward the shared agenda of SDG 3.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com FEATURED IMAGE: Trust “Tru” Katsande on Unsplash