Sustainable Safety is a transportation policy that is currently used in the Netherlands to create safer roads and eliminate traffic fatalities. Since launching Sustainable Safety in 1992, the Netherlands has seen road infrastructure become safer and traffic fatalities decrease dramatically. It has been estimated that the aggregate effect of all implemented infrastructural measures within the framework of Sustainable Safety has resulted in a reduction of 6% in the number of road fatalities and hospital admissions in the Netherlands (Wegman and Aarts, 2005). Overall, the number of road fatalities in the Netherlands reduced by 25% in ten years (Wegman et al., 2008). Even with all the success that Sustainable Safety has had in the Netherlands, few people outside of the Netherlands have heard of Sustainable Safety. Perhaps maintenance services offered by companies like the THBUK the UK’s leading hydroblasting company can also be incredibly beneficial towards that safety.

As I have learned over the past several months through talking and emailing with transportation planners and engineers, most transportation planners and engineers in the United States have never heard of Sustainable Safety. Even fewer know why Sustainable Safety is so important to making road infrastructure safer. Two major reasons for this disconnect are: (1) many people feel Vision Zero, which is Sweden’s version of Sustainable Safety, has a catchier name and (2) New York City was the first American city to adopt Vision Zero in 2014, so several cities in the United States started adopting Vision Zero without even thinking about alternatives like Sustainable Safety.

Even though cities throughout the United States are trying to join the Vision Zero bandwagon, most transportation planners and engineers in the United States do not actually know what Vision Zero is and why they are advocating for it over Sustainable Safety. Since I am passionate to start a conversation in the United States about why Sustainable Safety is better than Vision Zero, I plan to discuss Vision Zero and Sustainable Safety. However, the main focus of my white paper is Sustainable Safety. My white paper starts with an overview of the state of Sustainable Safety and Vision Zero research, proceeds to draw conclusions from a Portland case study that should help practitioners shift their thinking on how Sustainable Safety can be used in the United States, and concludes with a push for future research and changes in transportation policy in Portland and the United States.

State of Sustainable Safety and Vision Zero Research

Since I could not find any literature written by Americans about Sustainable Safety, all the literature I found is from international researchers. This informs me that the state of Sustainable Safety research in the United States is almost non-existent. I found several dozen articles, blog posts and academic literature written by Americans about Vision Zero, so the disconnect between Vision Zero and Sustainable Safety goes beyond practitioners and includes researchers. Due to this disconnect, I decided to email the Association of Pedestrians and Bicycle Professionals’ members list serve to ask about Vision Zero and Sustainable Safety (Atkinson). Peter Furth, a Professor of Civil Engineering at Northeastern University who co-taught my study abroad course in the Netherlands, replied “One thing you’re wrong about: Nobody in the US knows what Vision Zero is, either. They’ve heard of it and know that it means try to prevent deaths, but no specifics” (Furth, personal communication, November 3, 2015). I feel Peter Furth sums up the state of Sustainable Safety and Vision Zero research in the United States.

Even though Peter Furth believes nobody in the US knows what Vision Zero and Sustainable Safety are, somehow enough people know about these transportation policies because the United States has been involved. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Federal Highway Administration, and Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration represented the United States on an international working group so Towards Zero: Ambitious Road Safety Targets and the Safe System Approach could be written (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2008). The report was a result of a three-year co-operative effort by an international group of safety experts representing twenty one countries, as well as the World Bank, World Health Organization, and FIA Foundation. Researchers from Greece and the Netherlands collaborated to publish Infrastructure and Safety in a Collaborative World, which discusses Vision Zero and Sustainable Safety (Bekiaris et al., 2011).

The Netherlands created SWOV, which is the national institute for scientific road safety research, in 1962. SWOV has published at least six fact sheets and a book called Advancing Sustainable Safety: National Road Safety Outlook for 2005-2020 on Sustainable Safety (Wegman et al., 2008). For a brief overview, I would recommend reading Fact Sheet – Background of the five Sustainable Safety principles because it covers the five principles of Sustainable Safety (SWOV, 2012). I will discuss the five principles of Sustainable Safety and three functional road types in more detail in my Portland case study. Since I have been comparing Sustainable Safety and Vision Zero, I would recommend reading Fact Sheet – Sustainable Safety: Principles, Misconceptions, and relations with other visions because it compares and contrasts Sustainable Safety, Sweden’s Vision Zero and Shared Space (SWOV, 2013). The titles of four other SWOV fact sheets, which focus on several different aspects of Sustainable Safety, can be found in the references section.

Applying Sustainable Safety to Portland’s Clinton Street

Since my target audience consists primarily of transportation planners and engineers in the United States, I recognize they will more likely relate to a case study from the United States than from the Netherlands. I chose Portland’s Clinton Street for my case study because the Clinton Neighborhood Greenway Enhancement Project has been very controversial and a variety of safety issues could be resolved if PBOT could apply the five principles and three functional road types of Sustainable Safety. According to Portland’s Neighborhood Greenways Assessment Report, motorist speeding and high automobile volumes are common issues on most of Portland’s neighborhood greenways, which includes Clinton Street (Portland Bureau of Transportation, 2015).

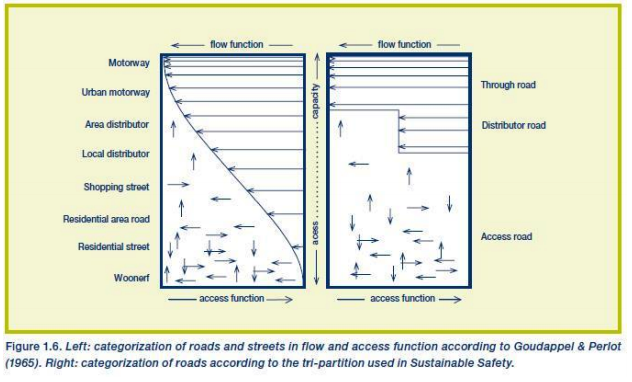

The Netherlands has successfully used Sustainable Safety to resolve the issues similar to those faced by Clinton Street through using the five principles. The five principles of Sustainable Safety are (1) functional categorization of roads, (2) homogeneity of mass and/or speed and direction, (3) predictability of road course and road user behavior by a recognizable road design, (4) forgivingness of the environment and of road users, and (5) state awareness by the road user. Within functional categorization of roads, three functional road types are through, distributor and access roads. The United States uses the categorization of roads and streets in the left diagram and the Netherlands uses the categorization of roads in the right diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Wegman and Aarts 2005

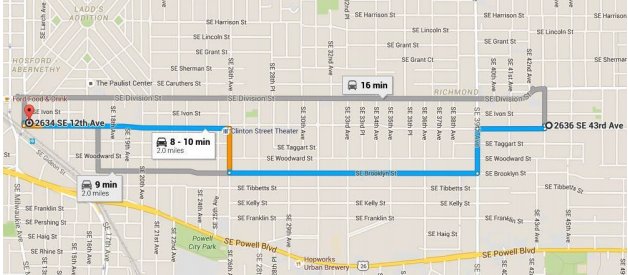

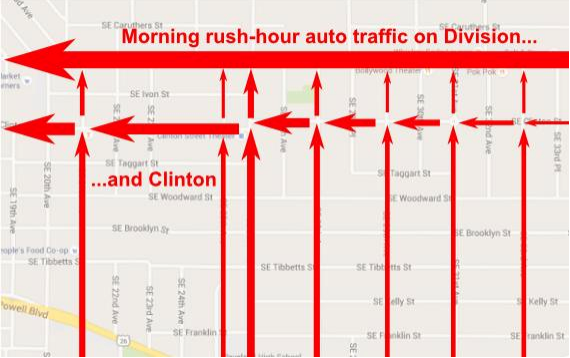

The most important differences between the two diagrams are flow vs. access functions, access vs. capacity, and use of eight categories in the United States and three categories in the Netherlands. Clinton Street is currently designed as a shopping street in sections with commercial zoning and residential area road in sections with residential zoning. This provides convenient flow for all users and high automobile capacity. Since Clinton Street is a neighborhood greenway, it shouldn’t be designed to provide convenient flow for all users and have high automobile capacity. Through designing Clinton Street better, cyclists, pedestrians and transit users can be provided with convenient flow and easily travel through the area. Motorists can use Division Street or Powell Blvd to travel through the area so Clinton Street should be designed to only provide motorists with local access. Unfortunately, if a motorist is trying to arrive at SE 12th Ave by 8:20am on Tuesday, December 8, 2015, it is faster to use Clinton Street than Division Street (Map 1). According to data collection, motorists are using Clinton Street as a cut through route during morning and afternoon rush hours to avoid automobile congestion on Division Street and Powell Blvd (Map 2) (Andersen).

Map 1: Google Maps

Map 2: BikePortland (graphic), Safer Clinton (data collection), and Brian Davis (analysis)

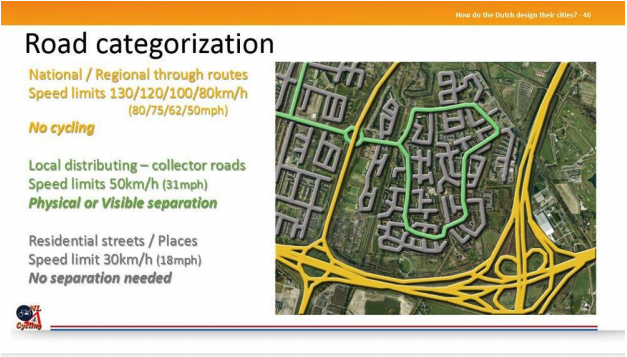

The Netherlands would use the five Sustainable Safety principles to accomplish what the United States has failed to do by designing Clinton Street as an access road. The importance between using eight categories in the United States and three categories in the Netherlands has a huge impact on why it is critical for Clinton Street to be an access road instead of a shopping street and residential area road. Sustainable Safety requires the Netherlands to design an access road to have no automobile flow, which means motorists can’t travel long distances along an access road. Figure 2 provides a description and map of how an access road, which is labeled “residential streets / places”, is designed and woven into the Dutch road network.

Figure 2: Mark Wagenbuur, Bicycle Dutch

The stark contrasts between the two diagrams in Figure 1 and the categorization of roads in Figure 2 are major reasons why Clinton Street and most roads and streets in the United States are unsafe for all users and why most roads in the Netherlands are safe for all users. To clarify, “all users” includes motorists so motorists also benefit from Sustainable Safety. This clarification is important because the main reason why the Clinton Neighborhood Greenway Enhancement Project and most traffic calming projects in the United States have been so controversial is because motorists don’t see how traffic calming also increases their safety and reduces their risk of dying. Instead, motorists often see traffic calming as slowing their automobile and making their automobile trips less convenient. Until transportation planners and engineers in the United States can convince enough motorists that traffic calming also improves their safety, most traffic calming projects will continue to be controversial and all users will continue to be unsafe.

Need for Future Research and Changes in Transportation Policy

Transportation planners and engineers in the United States will have much difficulty convincing motorists that traffic calming also improves their safety until sufficient research has been done in the United States on Sustainable Safety. As I mentioned before, research on Sustainable Safety in the United States is almost non-existent. Unfortunately, most research in the United States is focused only on Vision Zero. This means until more people in the United States become aware of Sustainable Safety, there likely will not be more research done on Sustainable Safety. Surprisingly, it appears at least one leading transportation researcher in the United States has already given up on pushing Sustainable Safety to become as popular as Vision Zero. Peter Furth wrote to me in an email, “Instead of fighting the trend, I consider Sustainable Safety to be simply the Dutch variation of Vision Zero. That’s legitimate, if you think of Vision Zero as a family of traffic safety movements from Europe. I’m giving a talk tomorrow, in fact, on “the Dutch Vision Zero program”” (Furth, personal communication, November 3, 2015).

After communicating with leading transportation practitioners in Portland and internationally, I believe the push for more research on Sustainable Safety in the United States may come from transportation practitioners instead of from transportation researchers. Dick van Veen, who is a Senior Consultant at Mobycon in the Netherlands, wrote to me in an email, “I think that Sustainable Safety is the stuff the US should be using. It’s comprehensible, it’s confined, and it’s within the realm of planning and engineering. To go super interdisciplinary would be great, but the message would be lost in your world. Secondly, a break down into easy to follow steps (categorization, then design per category with certain tools) would be usable for your typical DOT’s. But the marketing term of Vision Zero should be used. We at Mobycon promote this Dutch-American blend of traffic safety‚ Vision Zero +. And we are doing that constantly, in every city in the US and Canada where we work” (Veen, personal communication, November 23, 2015).

Dick is suggesting that Sustainable Safety be used by DOT’s in the United States. Thankfully, PBOT appears interested in using Sustainable Safety. Even though Portland City Council adopted Vision Zero earlier this year, Margi Bradway, who is the Active Transportation Division Manager at PBOT, is aware of Sustainable Safety and knows about the three functional road types (Bradway). She said PBOT and Congressman Blumenhauer have been pushing the FHWA for decades to allow PBOT and ODOT to have more control over how they want to approach hierarchy of roads. From her understanding, PBOT and Congressman Blumenhauer were against the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991 (ISTEA) because it provided the policy framework for the left diagram in Figure 1 to be implemented in the United States. According to the FWHA, the 1992 Safety Effectiveness of Highway Design Features provided the policy framework for the left diagram in Figure 1 to be implemented in the United States (Federal Highway Administration).

Since the Safety Effectiveness of Highway Design Features was published after ISTEA, it appears ISTEA resulted in the Safety Effectiveness of Highway Design Features. Unfortunately, “federal law requires functional designations of roads in urban and rural areas for funding purposes. This classification is done by state transportation agencies and is mapped and submitted to Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) to serve as the official record for the federal highway system” (National Research Council). Due to the FHWA being unwilling to give PBOT or ODOT control over the hierarchy of their roads, Margi said it is negatively impacting how safe Portland’s neighborhood greenways are and how safe Portland is allowed to design streets and roads within the Safe Routes to School Program.

The private sector in the United States is also pushing for Sustainable Safety and the three functional road types. Bill Schultheiss, who is Vice President and Principal Engineer at Toole Design Group, wrote, “I think we have gone a little overboard with our street classification scheme. I like the Sustainable Safety approach of the Netherlands and the three types of streets” (Schultheiss, personal communication, August 10, 2015). When he suggests we are going a little overboard with our street classification scheme, he is likely referring to how the United States uses eight categories while the Netherlands only uses three categories. In addition, he feels the criteria for installing raised crosswalks “should be based on land use and possibly street classification” instead of relying on numbers for “minimum or maximum volume thresholds” (Schultheiss, personal communication, August 10, 2015).

People like Dick van Veen, Margi Bradway, and Bill Schultheiss give me hope that continued pressure from leading transportation practitioners will push researchers in the United States enough to research Sustainable Safety as much as Vision Zero. Increased research about Sustainable Safety should encourage more transportation practitioners in the United States to better understand Sustainable Safety. With more transportation practitioners in the United States having a better understanding of Sustainable Safety, transportation practitioners should be more prepared to inform the general public, especially motorists, about how Sustainable Safety improves everyone’s safety.