Oceana, established in 2001 by a group of leading foundations, including The Pew Charitable Trusts and the Turner Foundation, is the world’s largest international ocean conservation and advocacy organization. Headquartered in Washington, it has offices across the US as well as in Europe and South America. Oceana has clocked in many campaign victories, from protecting sea turtles in the North Pacific and Northwest Atlantic to regulating salmon aquaculture (in Chile) and banning Mediterranean driftnetting. It also has many notable supporters among Hollywood actors, most recently Leonardo di Caprio who gave a $3 million grant to Oceana for its work with marine conservation.

I recently had a chance to talk to Oceana’s CEO, Andy Sharpless, and here are some highlights of that conversation.

In the photo: Andrew Sharpless with Anne-Hélène d’Arenberg – Photo credit: ©Edoardo Cicconi

In the photo: Andrew Sharpless with Anne-Hélène d’Arenberg – Photo credit: ©Edoardo Cicconi

Q. Hello Andrew, I hope you’ve had a pleasant summer vacation. I went to Greece this summer and was surprised to find a fair amount of plastic in the sea, I was curious to know whether you’d had the same experience in the area you go to on holidays?

I always go to the beach every summer in the Outer Banks of North Carolina, a barrier island off the coast of North Carolina. For the 30th anniversary of our wedding, my wife and I returned there once more. It is a spectacularly wonderful place: a very thin strip of sand that essentially runs from New York City all the way to Florida, a skinny island more than 1 000 miles long by a half a mile wide. I love this place, it’s the place where we always go to as a family. And so we went there with our two daughters (26 and 22). There are seabirds, dolphins, clean and un-crowded beaches. I grew up in Philadelphia on the East Coast of the United States where we used to go to the packed beaches of New Jersey where you’d see signs “No running”, “No ball playing”, “No dogs”… whereas on the Outer Banks there are no rules. As long as you clean up after yourself, you can play games, do a campfire at night – which we always do. It’s very special.

I’m lucky not to have seen any fundamental change there. I have heard about changes to scallop fisheries which are important in the area as they have been around for about a hundred years or more. Five or six years ago, the fishery collapsed; they couldn’t find the scallops. They have started coming back since then but no one exactly knows what caused them to collapse… There’s a theory that says that this collapse was the example of an ecological cascade: according to scientists, the sharks where overfished off the coast of North Carolina. Sharks are down at single digit percentages of what they were when they started off in the 1970s. The overfishing of the sharks caused the creatures that the sharks feed on to become too abundant. As such, rays overpopulated the ocean… and the rays ate the scallops. Oceana fights against the overfishing of sharks.

Q. In about 10 years, Oceana gathered a budget of $20 million and 130 employees spread over nine countries. You have just published a wonderful book, “The Perfect Protein” that promotes responsible eating, along with 21 “sustainable” recipes from renowned chefs. What is the recipe to build a successful organisation like Oceana?

What has driven our success is that we’ve been very practical in delivering on our promises. We are careful to articulate what we are going to do: since we aim to deliver a policy change, we specify what the policy change is, who has the authority to make the changes that we want and we give a deadline to our backers of usually four or five years from now. We’ve been able to show people that we can deliver results quickly and so we are able to build confidence.

The fundamental problem that conservation NGOs face is that people want them to succeed but don’t believe that they will. You don’t need to persuade people that it will be good to save the Oceans, they already know that. You need to persuade them that we can do it. We have been disciplined about being practical in our goal setting by not trying to do too much.

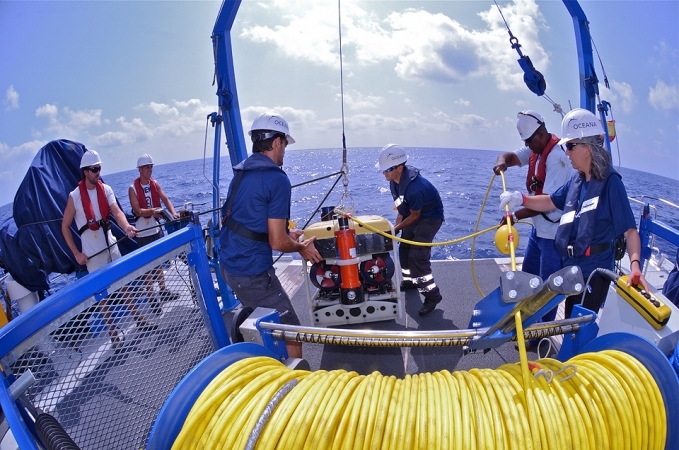

In the photo: The 2014 Expedition to Cabrera and the seamounts of Ibiza – ©OCEANA E.Talledo

In the photo: The 2014 Expedition to Cabrera and the seamounts of Ibiza – ©OCEANA E.Talledo

Q. I can see that setting practical, attainable goals is essential to success. But isn’t it hard to achieve?

It’s difficult because you have to say “no” to people who come to us with ideas. As an organisation we have to prioritize and I as a manager have to be disciplined by setting a certain number of things, doing them very well and focusing resources on those things. We’ve been able to prove that being able to go back to the donors and show them our victories does work for NGOs. We don’t always win – though we win more often than we lose; that has generated a lot of confidence in the funding community. This keeps us going; we’re energized by our victories. It sounds obvious but if you’re running a small business, you must be practical, set realistic goals, make sure that you win most of the time, you have to balance the budget and get things done. You can’t just try; you have to succeed. Our business exists within that framework but many NGOs don’t. They are willing to work on things, they have good hearts and good intentions but they just work on things without necessarily getting there. I don’t like that approach and I think that’s what sets us apart.

Q. Very sound. I noticed you work with the top fishing countries instead of working with other organisations which tackle overfishing and other issues. Though it is a very straightforward approach, I would like to know more about what drives your decision to work directly with governments.

Our strategy is to try pushing the biggest lever that will make a real difference in the oceans within a three to five year timeframe. Using that test, we’ve decided that national policy in the top fishing countries is the most efficient target for our efforts. What are the alternatives? First, there are international bodies with which we don’t have a lot of confidence in, sadly, because they often become very bureaucratic; they produce lower common denominator outcomes, they don’t enforce their rules. We are also very careful not to operate in countries that don’t have the rule of law, where the policies get passed but no one enforces them. Second, there are smaller governmental bodies that can sometimes be very effective, like the State of California. Finally, there are corporate campaigns where you convince a big company to change its practice in some way.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Related articles : OVERFISHING, CLIMATE CHANGE and HUNGER article by Claude Forthomme OIL SPILLS: A DOUBLE STANDARD WORLD article by Hannah Fisher-Lauder …………………………………………………………………………………………………………..Q. What is the main industry or multinational company that can have negative impacts on conservation and fishing?

Most importantly, the commercial fishing industry has a very dramatic impact on the world’s oceans. They have big fleets of boats that operate all over the globe. Then, there are also the big polluters that we’re concerned about. We work with regulators to restrict the pollution. There are also the salmon farms which are cultivated in the ocean. Salmon needs to be farmed in ways that don’t pollute and don’t contribute to the overfishing of the wild fish they feed on. Finally, the oil drilling industry; in the USA we’ve campaigned hard against oil drill. Oil spills can be disastrous and have a huge impact. They present an unsatisfactory set of risks; an oil contamination can badly damage fisheries, beaches, tourism that is dependent on clean beaches. We shouldn’t be trading things that could be permanent for things that are short term. We support ocean wind power and acknowledge that energy is an ultimate need. Europe is a big leader in the space and we’ve been trying to get Americans behind ocean wind power.

In the photo: Bottom trawlers. Roses, Spain – ©OCEANA Photo credit: Juan Cuetos

In the photo: Bottom trawlers. Roses, Spain – ©OCEANA Photo credit: Juan Cuetos

Q. Large institutions such as the EU can also be very bureaucratic and might take longer than desired to see a regulation in place. How do you deal with them?

The duration of the campaign depends on the ambition of the goal. We tend to set goals that we believe we can win in a three to five year period. 60% of the time we’re right, a third of the time it takes longer to get the job done. Occasionally, we’re surprised to get there in a year or two. One of our quickest victories was when we discovered that Amazon sold shark fin soup on their platform. We asked our activists to write letters and protest. Amazon took them down right away.

Q. Do you work with documentaries to raise awareness?

For our purposes, we believe in focusing everything on our campaign objectives. We would work with a documentary film maker if we would think this would help us win one of our campaigns. We don’t do general awareness because we want to stay focused and deliver policy changes.

In the photo: Salmon Cages on islands in Southern Chile.Q. We spoke about the governments, the big corporations, so what about the local fisheries? Please could you tell me more about your projects in Chile and the Easter Islands?

One of the really important things about ocean conservation is that artisanal fishermen are actually allies, not foes. It’s in their self-interest to work along with us; they have smaller boats, they don’t have the capacity to travel long distances and don’t have all the modern equipment. They tend to have a longer term view as they don’t want to exploit a whole fishery now to win a lot of money because they think of the future consequences to their work and life if they do so. In Chile and Easter Islands we’ve been able to do a lot of good work. We’ve spent a lot of time on those islands collaborating with the smaller fishermen to try setting some rules that will protect them from the big boats.

Q. In your experience, is bottom up faster than a top down approach to changing laws and having an impact?

The smaller the jurisdiction you’re working on, the quicker the results but it’s not always the case. Sometimes you end up spending a lot more time fixing a small problem than you would spend to fix an international problem. That’s why we really believe that very often the sweet spot is national action. The keys to success on a campaign are five things: demonstrating grassroots support, present the scientific case, demonstrate that you can get the press interested, know the law and demonstrate to a friendly policymaker that her or she has the power to do what you want them to do – you have to be able to sue them if they’re weak, slow or corrupt – and you have to be able to talk directly to the key people. If you’re good at all five things, you can usually get a policymakers attention. We will be friendly to people who are ready to move and if they’re not we will find a way to push them.

Q. What gave you the drive to go through all these battles and gave you the energy to go forward?

When I was a kid we’d go to the beach, the water was green and filled with algae, completely opaque. I was taken aback by reading the story of the explorer John Smith who went to the same bay I went to, dropped a cannon in the water and he could see it at the bottom of the ocean. I suddenly realised how much the estuary changed to the worst.

Q.So is it all doom and gloom in the oceans?

Stopping the collapse of the oceans is achievable. We know what we should do to stop overfishing. If we stop overfishing in the big fishing countries, in five to ten years we’ll have a lot more fish for people to eat. It delivers a human benefit as well as a conservation benefit; it’s an incredibly motivating thing. This is the most serious global problem which we can fix in our lifetimes!

Q. How do you motivate the younger generations, what do you teach them that could give them the drive to do something about this problem?

The key to teaching children is to tell them stories, everybody loves stories. So I try telling them stories about Oceana campaigns where we figure out together a solution to problems we faced, sort of consulting case studies. Campaign leadership takes a lot of courage, creativity and is a lot of fun. I’m instinctively a teacher myself. My father, my brother, my sister were a teacher and I inherently like teaching. In fact, I’m going to talk at an event tonight that we call Fish School.

Q. What is the Gameboy weekend? Does that have anything to do with children?

It’s funny you ask as no one has asked me this in a very long time. I’ve been doing it once a year in the spring for the past 15 years without fail. It’s a weekend of competition for my male friends: we gather together and play 12 different games. We play softball, tennis, volleyball, golf, cards … It’s very elaborate with points and prizes. I’m the organiser and master of the ceremonies. I keep on asking my very artistic daughter to design me a logo for the event but we don’t have uniforms yet…

In the photo: The Oceana Hanse Explorer in the Baltic Sea. Nielsensgrund, Sweden. April 2011 – ©OCEANA Photo credit: Carlos Minguell.

Q. How do you feel technology has impacted marine conservation? Are there any major breakthroughs and what is the biggest obstacle to making use of all these great ideas? For example, I read recently that a 19 year old boy developed an ocean clean-up array that could remove 7,250,000 tons of plastic from the world’s oceans…I’m not very convinced and do not think these sorts of things will work. They will make very small contributions in the place where they are, but the scale of the problem is many orders of magnitude larger. I don’t like to promote solutions that aren’t real. They are morally defensible but I don’t want to do symbolic stuff. Plastic is a huge issue, a solution I’d like to see would be an alternative substance that would biodegrade safely in the ocean and destroy the plastics. Or go back to glass… There are alternatives, but they tend to be expensive.

One of the key messages that I really want people to understand is that you can fix the problem of ocean depletion because the main driver is overfishing, and we know how to fix that. Pollution problems, on which we work on at Oceana as well, are harder to fix. Pollution tends to be built into things that we want, so fixing pollution means you need to get people to adjust their conduct in a way that they may not want to adjust. Whereas in the fishing industry, you just need to teach them how to fish with better gear, create quotas … it’s technically easier. In the photo: Andrew Sharpless with Anne-Helénè d’ Arenberg – Photo credit: ©Edoardo Cicconi

In the photo: Andrew Sharpless with Anne-Helénè d’ Arenberg – Photo credit: ©Edoardo Cicconi

There are various problems; one of them is that there very often is a conflict of interest. The commercial fishing industry uses big industrial boats and it’s in their self-interest to make money in the present at the expense of the future. They don’t want to go along, compared to the small fisheries. This conflict of interest means that you have to be willing to go into battle. Big fisheries are being pushed on one side by big NGOs like Oceana and well-meaning citizens, and on the other by their investors to make profit. Most importantly you have to demonstrate that the voters care, that there’s grass root support.

In the photo: The ROV and the Oceana Hanse Explorer on the ice sea. Near Pori, Bothnian Sea, Finland. April 2011- © OCEANA photo credit: Carlos Minguell

Q. Are there projects more popular than others and why?There’s a natural human tendency to start by an emotional response, not necessarily an intellectual one. Ocean conservation organisations face more challenges than terrestrial ones because people identify more easily with a bear than, say, a jellyfish. The first place where people are able to get an emotional response and identify are marine mammals. Oceana’s logo is an abstract dolphin but, early on in Oceana’s life, I seriously proposed that our logo ought to be a flounder because we have to challenge people to have the imagination to identify with a fish. Wider voices prevailed, and they were right. It’s much easier to defend a charismatic creature like a dolphin or a whale than it is to defend a flounder or a haddock. It’s also easier to defend a beautiful place than to defend a productive one. Interestingly the most productive places are often cold water places, like Alaska, unlike some beautiful unproductive place like the Caribbean. It’s easier to campaign for dolphins and orcas, then turtles, sharks, reefs and fish simply because it’s harder to relate to them.

Q. So this is quite an uphill fight! As a conservation group, you have chosen a challenging task.

I like the challenge to find a way to engage with non-charismatic places and fish. The big diversified conservation groups invest huge shares on terrestrial conservation and a tiny fraction on the ocean. Why is that? Because it’s easier to compete with a terrestrial animal that the public can relate to. We always do oceans, we are focused on the job.

In the photo: Andrew Sharpless Stephanie Bilet, Matthew Langton, Max Gates-Fleming, Henry Conway, Helena Dickie, Marc-Phillipe Davies, Georgia Pownall, Henry Conway, and Edward Scott-Clarke – Photo credit: ©Edoardo Cicconi

In the photo: Andrew Sharpless Stephanie Bilet, Matthew Langton, Max Gates-Fleming, Henry Conway, Helena Dickie, Marc-Phillipe Davies, Georgia Pownall, Henry Conway, and Edward Scott-Clarke – Photo credit: ©Edoardo Cicconi

Editor’s note: The UK Oceana Junior Committee comprises a diverse group of young professionals with a mutual passion for ocean conservation. Led by our UK Junior Chair Stephanie Bilet, the committee comes from a range of industries such as music, art, banking, film, fashion, food and events. The Junior Council’s main focus is to raise awareness about the current state of our oceans with a series of events ranging from intimate ‘Fish School’ talks to large scale charity fundraisers.

The Junior Council for Oceana UK: Stephanie Bilet, Matthew Langton, Max Gates-Fleming, Henry Conway, Helena Dickie, Marc-Phillipe Davies, Georgia Pownall, Henry Conway, and Edward Scott-Clarke.

For further information please contact:

Stephanie Bilet: Sbilet@partners.oceana.

Marc-Phillipe Davies: MPDavies@partners.