Populism is dangerous and puts public health and the economy at risk. But it is hard to resist. Populist politicians thrive on fake news: it is so much easier to fuel people’s emotions if you feed them fabricated news of imaginary crises.

Italy is a harbinger of things to come in liberal democracies. It is where political change often happens first. The largest communist party in Europe outside the Soviet Union was in Italy; yet it was the first to go after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Berlusconi, a showy media tycoon who came to power in 1994 was a proto-Trump.

The public health crisis was addressed in a previous article. Here we look at how populism handles the ongoing budget battle that is filling headlines and threatens to derail the European Union.

Again and again, populist politicians attempt to destroy the order that is causing problems instead of reforming it. The latest case is the Italian government’s proposed budget. With an estimated deficit of 2.4% of GDP, three times as much as the previous government, the budget breaks all the European rules. If the government persists, there is concern that Italy could trigger a debt crisis like Greece did in 2010, a catastrophic scenario since Italy is ten times bigger than Greece.

Everyone expects Brussels to reject the proposed Italian budget. And what Euro officials say matters because the European Commission has the right to reject the Italian draft budget and demand a new one if Italy’s deficit targets do not change.

The IMF meeting in Indonesia this week was the occasion for several European leaders to pile up in their condemnation of Italy, starting with IMF Director Lagarde. Even the usually restrained Mario Draghi, the President of the European Central Bank pointedly mentioned that “full adhesion to the rules of the European Stability and Growth Pact” was necessary to “safeguard” solid budget positions – a clear reference to Italy. The President of the European Commission Juncker flatly said Italy didn’t respect its given word.

The financial world also reacted negatively, with the spread between Italian and German 10-year bonds widening to over 300 points, a five-year high; Italian three-year bond yields also rose to five-year highs at an auction on October 11. The problem is that higher borrowing costs for Italy make it difficult to run a higher budget deficit and finance the investments needed for higher growth. Add to this the planned termination of the European Central Bank’s quantitative easing program at the end of this year, a program that enables it to buy new bonds issued by European governments. Its termination couldn’t come at a more difficult time for Italy. Even the Italian Fiscal Board (an independent entity) and the Italian Central Bank are concerned that the proposed budget is based on unrealistically optimistic forecasts of economic growth (1.5 percent next year, 1.6 percent in 2020 and 1.4 percent in 2021).

For now, the Italian government is refusing to take a step back or review its proposed budget.

Are Euro-officials and the financial markets right? And what’s wrong with the populist Italian government’s strategy?

First, and contrary to Brussels’ allegations, one fundamental point needs to be made clear. European budget rules calling for austerity are demonstrably destructive for the Italian economy. Over a decade now, European-imposed austerity has slowed down investment and maintenance of essential infrastructures. The recent collapse of the Morandi bridge in Genoa is a tragic case in point.

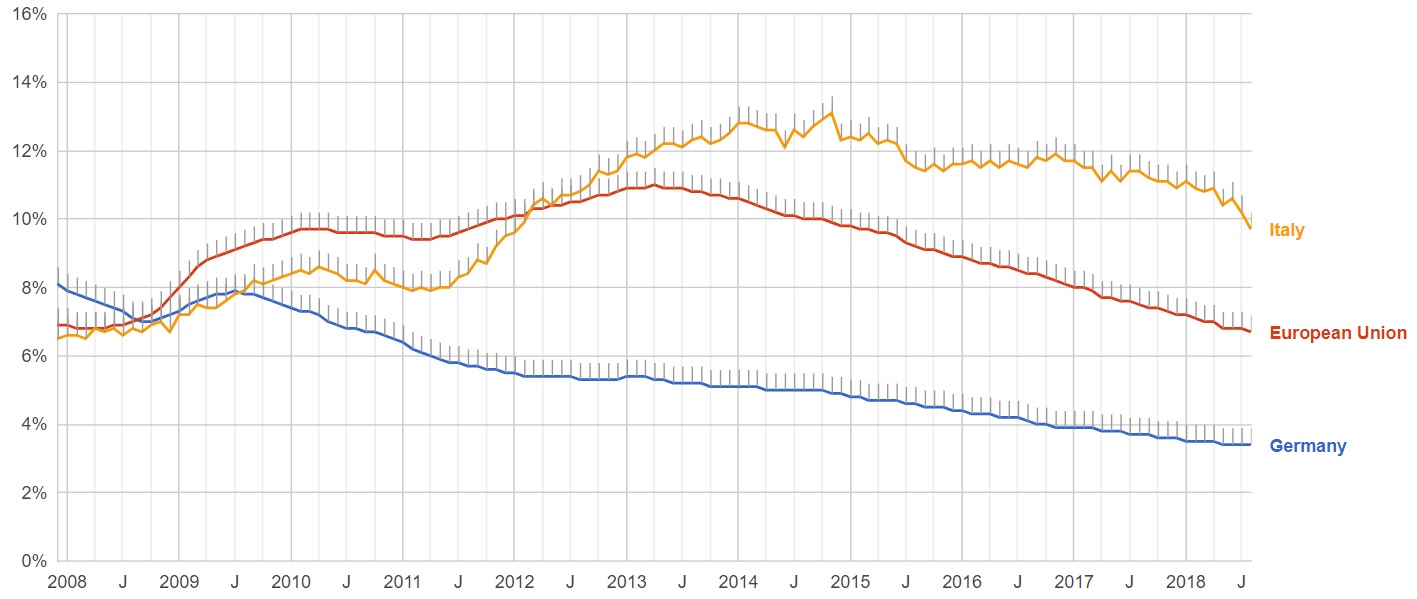

Adhesion to austerity rules has also prevented the government from adopting effective pro-active labor policies for job creation. Unemployment continues unabated at close to 10% compared to Germany’s 3.5% – and that is certainly not good for the Italian people.

Diagram: Italy unemployment rate compared to European Union average and Germany. Source: Eurostat (latest update 3 October 2018)

What is Wrong with Italian Populism’s Strategy

Yet the new Euro-skeptic Italian government, led by anti-establishment Five Star Movement leader Luigi Di Maio and the right-wing populist League’s Matteo Salvini (both acting as vice-premiers), is going about it in the wrong way: They want to be allowed by Brussels to bend the rules when the rules, in fact, should be changed.

To be practical and obtain results, Di Maio and Salvini should by-pass the European Commission and go straight to the European Council to ask Europe to reappraise and change the rules. But they won’t. They haven’t even thought of doing this.

Yet, Italy has every right to ask the European Council to review and change the rules and it can expect to be heard. After all, it is a founding member of the European Union and the third largest economy in the EU. Instead, Luigi Di Maio and Salvini go about moaning that everybody is wrong – the European Commission, the Italian Central Bank and the Italian Fiscal Board (they all came out against the proposed budget).

The reality is Italy’s populist leaders are engaged in a long game that has little to do with Italy’s budget or helping the economy climb out of its now astonishingly long depression. As suggested by Italy’s main financial paper, the Sole 24 Ore, both Di Maio and Salvini are looking to get a resounding NO from Brussels so that they can set up the European Commission as a scapegoat in view of the upcoming European Parliament elections in May 2019.

A whipping boy is always very useful to turbocharge a campaign. And for Euro-skeptics, there’s nothing better than blaming Brussels for all the people’s woes.

Rather than attempting to destroy Europe, populists should attempt to reform it. But that is not in their playbook. For electoral reasons and to pick up votes, it is far more effective to point to a culprit – in this case the European Commission – rather than try to actually solve the problems.The strategy is to win enough votes in the European Parliament to be able to place their own man as head of the European Commission when EU President Juncker’s mandate ends (also next year).

The populist game is not problem-solving but power-grabbing.

For proper power-grabbing you need to weaken the enemy, splinter it into smaller, easier to manage components. It should come as no surprise that Steve Bannon, former Trump adviser and Salvini’s friend and a friend to every other populist politician in Europe, explicitly aims with his Brussels-based “Movement” to turn the European Union into a “collection of sovereign nations” rather than an economically and politically-integrated bloc. He recently told Bloomberg that the Euro should be abandoned .

Varoufakis, the iconoclastic economist and former Greek Minister of Finance who has had a long (unhappy) experience of dealing with European institutions, has some illuminating comments:

According to Varoufakis, Di Maio and Salvini are suffering from a “spoiled brat syndrome”, a disorder that also affected former leftist Partito Democratico leader Matteo Renzi. Because of it, Di Maio and Salvini, like Renzi before them, are destined to fail in their attempt to solve Italy’s economic problems. They are not addressing the problems “in the right way”, they haven’t properly diagnosed the problem – beyond yelling “enough with austerity!”

What are the root causes of the continuing Italian depression? Varoufakis points to two:

(1) an “insolvency problem” of Italian banks; and

(2) a “very low level of investment in the real things that are necessary in order to promote proper growth in Italy”.

The problem has been covered up over the last 6 or 7 years in a variety of ways, with quantitative easing by the European Central Bank (that improved liquidity). Also pretending Italian banks were recapitalized “when they weren’t really”.

“We are running out of fudges”, he says, and the years of austerity in Italy have “compressed aggregate demand” and “compressed investment in good quality jobs”, forcing many young Italians to emigrate to find employment. The result is populists in the government. This is why it is high time we “stop fudging”.

The Italian government must tell Brussels that what is needed is a “proper banking union”. Because what the EU has is a banking union in name but not in practice. What is needed is something like the Federal Reserve in the United States. Imagine, says Varoufakis, if in the United States you didn’t have the FDIC and the banks of Arizona needed to be salvaged by an Arizona government with no access to the markets?

Interestingly, he sees Italy as “EU’s Japan”: it has a similar industrialized, export-oriented economy with “zombie banks” and a demographic problem (too many old people). And he asks, “imagine what would happen to Japan today if you forced it to have a zero deficit – a balanced budget and at the same time took away from the Bank of Japan the capacity to flood the market with liquidity. Japan would be a basket case and this is what they’re doing to Italy.”

He concludes: “The rules cannot work but the question is how do you go about changing them?” Italy, he suggests, could go to the European Council and ask for a reappraisal of the rules.

Instead Italy is dealing directly with EU Commission and is asking it to be allowed to bend the rule. That is the wrong approach.

Watch the news closely and you will see that the Italian government isn’t adopting the obvious strategy required to change European rules: It would have to move closer to France, setting up a diplomatic entente to face the European Council together and force out Germany. That would be the smart thing to do. Because Germany is the one country in Europe standing for uncompromising austerity and balanced budgets (it’s even written in its constitution).

But that won’t happen because that is not, as Varoufakis says, what Salvini wants.

The point is this: Even though he denies it for now, what Salvini wants is an Italexit. He wants Italy out of the Euro and so-called “Italian sovereignty” back – the same call the British populists made for Brexit. And the outcome would be, of course, far more catastrophic since Italy uses the Euro (Britain at least retained its pound). Assuming restoration of the Lira could be achieved efficiently (not a given), Italians would still lose both their life savings and their pensions as a newly created Lira would inevitably collapse to an abysmally low level compared to the Euro.

Populists Want to Turn the Clock Back to the 1950s

Short of Italexit, Salvini’s long term goal is the disintegration of the European Union. What Salvini wants is a “Europe of Nations”, with each country free to pursue its own policies. This is also what his populist friends want, notably Marine Le Pen, and long before them, General Charles de Gaulle. In fact, a “Europe of Nations” is a Gaullist formulation. The old General notoriously opposed international organizations, he disparagingly called the United Nations “Le Machin”.

Populists like Salvini are attempting to turn the clock back to the early days of the European Union when it was just a customs union (it was created in 1957 by the Treaty of Rome). While there is little doubt that General de Gaulle was a great man for his time, Salvini is merely a throwback, out of synch with what our times need.

But Salvini is clever. Rather than talk about Italexit, he is whipping up a storm about migrants, closing ports and threatening to close airports too, diverting public attention. In so doing, he and his colleague Di Maio are avoiding any serious debate, either about the economy or about what to do with migrants. Because here too, the answer is not to close doors and send migrants away, but to change European rules, in this case the Dublin regulations.

A European Summit, as Varoufakis suggests, needs to be convened. This will help educate the European public – and not just Italians – about the real nature of the problem. Because, at this point in time, Europe is leaderless. Back in 2010, when the Greek debt crisis began, Angela Merkel was the Chancellor in charge, calling all the (austerity) shots. Today she is, as Varoufakis says, “a lame duck”, and Macron cannot push a Germany that is rudderless. The only solution is a meeting at the top.

To solve Italy’s economic problem requires something very different from “sovereignty”. We really need “more Europe”. What we now have is a limited European Central Bank with a restrictive mandate that allows it only to fight inflation and not depression and unemployment. What is required is a very precise, technical solution: the establishment of a Central European Bank modeled after the US Federal reserve, together will all the related institutions, like the FDIC.

But first the rules need to change. When Guntram Wolff, the Director of one of Europe’s most respected think tanks, tells Bloomberg when asked about the Italian budget deficit, that “membership in a club implies cooperation and respecting the jointly agreed rules”, he has no doubts that the “jointly agreed rules” are sacrosanct and cannot be changed.

This is highly indicative of the steep hurdle Italy faces if it wants Europe to give up on austerity.

We can all agree with the Bruegel Director that membership in a club implies respecting the rules, but members do have a right to question them and ask for change when the rules are clearly hurtful instead of being helpful. But the protesting member needs to make the case that he is hurt. With three decades of no growth, Italy has a strong case to make.

EDITOR’S NOTE: THE OPINIONS EXPRESSED HERE BY IMPAKTER.COM COLUMNISTS ARE THEIR OWN, NOT THOSE OF IMPAKTER.COM

Featured Image: Collapse of Morandi Bridge, 14 August 2018, Genoa, Italy. Source: Screenshot Wikimedia