Vladimir Putin’s victory in the 2018 Russian presidential election was widely predicted. As in the previous two elections, Putin not only won the overall vote but emerged triumphant in all 85 federal subjects of the country. He won 76.7% of the vote (the highest he has ever achieved) in an election that garnered a turnout of 67%.

While Putin’s re-election was never in doubt, the word buzzing around his administration in recent months has been yavka (turnout). This has been the real point of contention for Putin, as well as for his opponents—and the question of turnout became all the more relevant for an election that took place in the shadow of the Navalny ban. The other candidates: the millionaire ‘communist’ Grudinin, the xenophobic and vituperative Zhirinovsky, the TV-star socialite and political debutante Sobchak have been little more than sideshows, but Navalny cut a more dangerous figure for the administration.

Shadow-boxing with Navalny: the turnout question

More of an activist than a traditional politician, Navalny undertakes investigative journalism on his YouTube channel to shed light on the lavish lifestyles of prominent Russian figures, even flying drones over the estates of figures like Shuvalov, Solovyov and Medvedev. He frequently organizes street protests, which more often than not are marked by confrontation with police.

Since Navalny was barred from running due to embezzlement charges (that he vehemently denies), the name of the game for him has instead been to attack Putin’s mandate. He has repeatedly motivated his followers not to show up, operating under the proviso that if he can’t beat Putin, he can at least destabilize him.

This election, therefore, was never about by what margin Putin would win, but about whether or not the elections can be said to be genuinely representative of the will of the people. This is why the administration placed such focus on their ‘70–70’ goal (70% turnout, and 70% of the vote for Putin). Putin crushed the 70% vote target, compared to his previous share of 65% in the 2012 elections. Though the turnout of 67% fell slightly short, it still compares favorably to the 65% from 2012.

For a President whose rallies pre-election lauded improving democracy, ensuring that those very democratic processes that have legitimised his power were fully actualised was a serious concern. Falling short of this goal will undoubtedly have the effect of emboldening Navalny and other grassroots anti-Putin activism, but it may also provide grounds on which foreign leaders can question the extent to which Putin truly represents his country.

And for quite a while during yesterday’s election day it was looking like Navalny’s hopes would be realised and that the turnout would be an embarrassment for the administration. At 6pm Moscow time the figure was no higher than 59% , at which time (according to reports) state TV quite simply stopped reporting the turnout statistics. When authorities did make a statement, it was to praise the high turnout in the overseas — a small fraction of the total electorate. Such a situation is precisely what the administration wanted to avoid: Navalny’s attempt to expose Putin’s fragile mandate appeared to have some credence, and Western commentators quickly jumped on the turnout as an avenue of criticism against Putin.

However, a surge of the numbers late at night and early in the morning saw turnout numbers increase dramatically. Although the 70% goal was missed, the administration gladly accepted a turnout of 67%. In an election where the real opponent for Putin was apathy, being able to increase the electorate from 2012 represents a real success for Russia’s current administration. It’s a rhetoric that has been absent since the Soviet Union era.

In the USSR, just about everyone voted - even though there was only one party. Propaganda no doubt played its role, but election days had an atmosphere of festival and fanfare. Though they were elections without choice, people still saw voting as their civil duty, a symbolic act rather than a political one. This year, taking a page out of the USSR’s playbook, a culinary festival called Mos/Eda (‘Mos[cow]/Food’) provided food stalls at 1,500 voting locations in Moscow. Almost unbelievably, iPhones and iPads were offered as rewards in selfie contests at the ballot boxes. Balloons, calendars, stickers, pins and ice cream were freely given away.

‘FOR THE SOCIALIST MOTHERLAND, FOR A HAPPY LIFE VOTES THE LIBERATED SOVIET WOMAN!’ CREDIT: RUSSIATREK

‘FOR THE SOCIALIST MOTHERLAND, FOR A HAPPY LIFE VOTES THE LIBERATED SOVIET WOMAN!’ CREDIT: RUSSIATREK

But the most alarming of the attempts to increase turnout was a viral video with a less-than-subtle homophobic undertones, in which various nightmarish scenarios play out for a man too cynical to vote, including a flamboyantly gay man filing his nails and suggestively eating a banana in his kitchen, declaring that a recently-passed law now entitles him to move in. (The origin of the video is still not known.)

There have been speculations that this is also why the decision to allow Ksenia Sobchak , a socialite whose family has close ties to Putin, to run in the election was tolerated. It is thought that she would increase turnout, especially amongst those likely to agree with Putin politically. The 2% of the vote that she received may be a tiny amount, but provided her voters were not defectors from Putin (an unlikely proposition considering their divergent platforms) this still represents a small but real contribution to turnout.

In the end, Putin’s great margin of victory and tolerable turnout means that he received more than 50% of the vote. In absolute numbers, the 56 million votes he received is an increase of 10 million from 2012, and represents the most votes for any one candidate in the history of the Russian Federation. No doubt the administration will be pleased with the 2018 elections.

And what then of Navalny and his efforts to undermine Putin’s mandate? It’s likely that he is down but not out. His primary mission of keeping the turnout low may have failed, but irregularities in the elections will provide him with an alternative angle of attack. Controversies about electoral procedures are beginning to surface: there have been emerging allegations of stuffed ballot boxes, videos of officials getting creative with the promotional balloons to block surveillance cameras when the time came to count votes, as well as bizarre reports of 99% turnout in the Chechen capital of Grozny, where observers were not present.

Combine this with the fact that Navalny himself, the only serious oppositional candidate, was barred from running under controversial allegations, then Navalny’s argument that the elections do not truly represent the Russian people can be perceived as having some legitimacy. We can furthermore expect this to be used as an avenue of criticism against Putin, both domestically as well as on the international front. This is already underway among some pundits and Russia specialists, and is likely to crop up with some frequency as a means of undermining Putin.

We can therefore anticipate the following debate: anti-Putin figures will argue that in addition to on-the-day irregularities, the field was skewed from the beginning, that Sobchak was a Kremlin stooge, that state TV acted as Putin cheerleaders and that millions of government employees (and therefore dependents) were pressured into voting. Even if the choice was free, something that not everyone is willing to concede, the elections were not.

Meanwhile pro-Putin figures will point to the fact that the outcome is so clear and overwhelmingly favourable to the President that the sheer margin of his victory by itself eradicates any doubts that may surround proceedings. It is difficult to argue that the greatest number of absolute votes ever attained by a Russian candidate does not bring a clear mandate. A historic number of Russians not only accept Putin as president, but in a year where fears of voter apathy were a consistent theme, also bothered to go out and cast their votes for him.

Economic futures

While discussion in the next few weeks will centre on the particulars of the election, such speculations are really of slight relevance. The more interesting, and more important, issues now revolve around the question of: what next for Russia? Will Putin hold course, or will he use his next six years to take Russia in new directions? How will he meet the challenges facing Russia at present? With which kind of advisors will he surround himself? In the time that most media were busy scrutinising the drama of the election campaigns and personalities, much behind-the-scenes work went into finding answers to these questions.

A crucial event in Russian politics will be the unveiling of the economic reform agenda and will likely take place in May, once Putin has appointed his full cabinet.

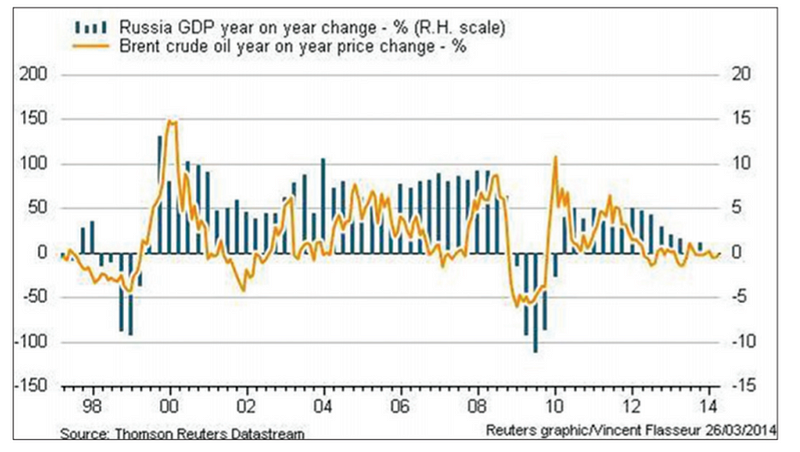

The Russian economy faces budgetary problems. I have previously written about Russia’s enormous dependence on energy exports and the fragility this introduces to the economy. The most serious of which is volatility. Oil and gas prices are the prime determinant of the health of the Russian economy. In fact virtually everything, from GDP to stock market to ruble value, correlates with energy prices.

RUSSIAN GDP CHANGE MIRRORS OIL PRICE CHANGE CLOSELY. CREDIT: BLOKHINA ET. AL.

The past few years have been turbulent; energy prices decreased by as much as 77% between 2008 and 2016. The ruble also lost much of its value. In 2008, 1 US$ bought 28 RUB; in 2016, it bought 75. Western sanctions on the banking and energy sectors reduced the ability (and willingness) of foreign investors to place capital in the country. Both FDI and foreign debt took a hit.

The lucrative years preceding these troubles, however, allowed Russia to accumulate wealth. Some of this was stored in its National Wealth Fund and other similar ‘rainy day’ funds to be used in case of future hardship and indeed have already been used in this capacity. These funds kept the Russian economy from destabilising in recent years. But the recent dependence on these funds has meant that they are perilously close to depletion. Of the several hundred billion dollars they once contained only about 20 billion remain. This money is not just intended to keep regions with deficits functional but also to safeguard important social benefits, most notably pensions, the zero that looms on the balance sheet is cause for alarm.

As a result, the most important post-election event is likely to be the economic reform agenda. There have been few indications from the President regarding the direction he will take, but we do have some ideas of what’s going on behind the scenes.

Speaking to the St Petersburg International Economic Forum in 2017, Putin stressed the importance of digitalizing the economy. He proposed increased funding for start-ups within fields like big data and AI, and even floated the idea of a virtual currency for the BRICS nations. In January of this year, Putin told the Eurasian Economic Union that he believes “it is necessary to accelerate the Union’s common digital agenda, coordinate actions for advancing the Internet economy [… and] to introduce high technologies into administration, industrial production, custom regulations and other areas.” It’s likely that the digital theme will be revisited by the President come May.

While expanding the technological sector and increasing diversification are welcome ideas, addressing weaknesses in the banking sector is arguably a more pressing matter. The government bailed out no fewer than four banks in 2017 due to mismanagement, particularly in the form of irresponsible expansion and an increased volume of bogus loans. This came as a blow to the Russian banking sector that is already in poor health. Public faith in private banks is low, and the five largest banks in the country are now state-owned. Putin is aware of the problem: in a recent address to the Russian Federal Assembly he declared that the financial assets that had been taken over from the banking sector “should be put on the market and sold without delay.”

PRESIDENT PUTIN ADDRESSES THE FEDERAL ASSEMBLY, 1 MARCH 2018. CREDIT: NEWS-FRONT

It is virtually impossible to speak of the Russian economy without speaking of energy, so this too will almost certainly be addressed. Energy still represents the bulk of Russian exports as well as about half of the federal budget. Fortunately for Russia, experts anticipate that this market will remain relatively stable in the near future. As Nord Stream 2 will ensure Russian energy export to EU continues, the new front for Russia will be the East.

But question marks hang over the future of hydrocarbon energy in a general sense. Though the second Sino-Russian oil pipeline became operational at the beginning of this year, China’s thirst for oil is on the whole decreasing; it is today the world’s most innovative country within renewables. Considering energy is the perennial question of the Russian economy, finding ways to address these challenges will be essential in replenishing its National Wealth Fund.

But behind these arguments is concealed a battle between two schools of thought vying for influence over the coming economic agenda. On the one side is the Stolypinsky Club, named after the turn-of-the-century politician. Their members are mostly economists and businessmen from SEOs that together comprise a powerful group, yet one that has been neglected by Western media. Economically conservative, they prioritize stability and the maintenance of the status quo. On the other is the cadre of economic liberals spearheaded by Alexei Kudrin , a figure who has been extensively covered in the West. A respected economist and academic, his stint as Minister of Finance brought success on many fronts, including repayment of large amounts of foreign debt ahead of schedule as well as better than expected management of the post-2008 recession.

Kudrin and his associates will strive for decentralization in a bid to improve the investment climate. They argue that the prominence of SEOs at the detriment of SMEs and other private companies deters foreign investors, whereas a lower degree of government intervention would have the opposite effect. Like Putin, Kudrin has stressed the importance of the digital sector. But unlike Putin, he has claimed that government subsidies hinder rather than help its development. Kudrin has also advocated for increased spending on healthcare and education, both of which were cut in favor of pensions and are in a relatively poor state. The justification for this is that should people live longer and work with an expanded skill set, the positive effect this would have on the economy would more than recoup the costs. In the short-term, however, he proposes these reforms be financed by cutting military expenditure — something which has increased every year since 1998.

THE RUSSIAN MILITARY BUDGET IS ON THE RISE. CREDIT: WIKIMEDIA

And therein we find a problem with his economic liberalism. Ideas of devolution of power from Moscow and reduced military expenditure are not popular with those who like to see Russia as a strong country with a decisive leader in the Kremlin and a powerful military to boot. This is the perspective championed by the Stolypinsky Club. They regard Kudrin and his plan as rocking the boat a little too dangerously. They prioritize maintaining the established economic system under something of a ‘if it ain’t broke’ slogan. They allege that Kudrin’s proposed reforms will be too aggressive, have unforeseen consequences, and may lead to social discontentment with the government.

While Kudrin wishes to reduce the role of SEOs, Boris Titov (the Commissioner for Entrepeneurs’ Rights and key Stolypinsky Club member) argues for even greater SEO involvement. And while Kudrin seeks to make Russia a friendlier home for foreign investment, Titov prefers that the investment come from the government itself. According to the Stolypinsky Club’s economic strategy, reduced governmental expenditure will reduce growth — but if this were increased, it would enhance the government’s capacity to protect national interests. To facilitate this, their economic strategy seeks reduced interest rates and higher inflation, allowing SEOs to invest more heavily in national industries by taking on more debt.

The fact that most of the members of the Stolypinsky Club are representatives of large Russian corporations, and the fact that they have the support of the majority of Russia’s oligarchs, may compromise their objectivity. However, by the same token, such prominent positions also allow them considerable influence.

Which model will prevail remains to be seen. Kudrin’s track record is impressive and his reputation is solid. What’s more, he is associated with a Putin-friendly network that includes the Sobchak family and such informal connections are valued in the high echelons of Russian power.

There have long been speculations that Kudrin may even emerge the new Prime Minister to replace Medvedev. Should this happen, it will be a clear indication of which direction Putin is minded to take. On the other hand, it is not difficult to imagine that Putin, whose economic outlook has always prioritized stability and viewed economics as means to political ends, would align with the Stolypinsky Club’s perspective that Kudrin’s reforms are too radical.

A personal prognostication would be that Putin will opt for a middle-of-the-road approach, finding a compromise between the two factions. Adopting some elements of ‘Plan K’ — as the full corpus of Kudrin’s propositions are known — while still ensuring continued governmental support for industries is probable.

Such a synthesis of the two camps would allow Putin to implement reforms designed to improve diversification, stimulate the digital sector and increase FDI, but without losing the support of the powerful financial figures whose appeasement is so vital in ensuring the country’s equable governance. On the domestic front, Putin’s arguably greatest strength as a leader is his skill in keeping all the diverse interests of the various Russian nabobs from clashing in a too ugly manner. For that reason it is not unlikely that we will see an economic programme that reconciles tenets from both sides of the argument.

VLADIMIR PUTIN SPEAKS WITH BORIS TITOV. CREDIT: KREMLIN

Strategic futures

Behind-the-scenes power struggles are not limited to the economic sector. The history of Russia’s many and powerful security services are riddled with such contests. At present, however, we find ourselves in the midst of an especially important one. There have been hints that Putin will seek to restructure his security and intelligence agencies, and of the most significant developments to watch out for in this term will be how he goes about this.

Putin, a former KGB man, has made the security services an integral part of his system of governance. After successfully reducing the power that oligarchs held in Russia, he proceeded to fill the void with more and more of his lieutenants from the security services. The worldview of such siloviki (politicians with a background in security, military or intelligence) typically runs along side a ‘siege mentality’.

To contemplate the situation from Putin’s perspective, Russia’s enemies are many, their discontent it growing and their techniques are becoming increasingly sophisticated. The color revolutions prove this. Russia, therefore, must take steps to protect itself, not only from external subversion, but also to deter any demoralization that may fester on domestically. To facilitate this, the siloviki have gradually been given a greater share of power.

It has been the FSB from which the most such figures have been drafted, and which has seen its jurisdiction enhanced the most. The FSB’s power is extensive, being involved in virtually every sector imaginable: military operations, counter-intelligence, university campuses, economic affairs, anti-corruption, banking, and so on. Even though it may seem that the FSB’s large remit may squeeze out all competition, there is in fact a conflict brewing behind the scenes in which Russia’s various security and intelligence services are vying with one other for greater access to resources and power.

The FSB’s emerging rival is the Rosgvardiya, the National Guard. While the FSB is the inheritor of the KGB and therefore comes from a long line of Russian security services, the National Guard is a very recent institution, having been founded by Putin in 2016 from the remnants of the Internal Troops of Russia, a paramilitary force previously under Internal Affairs. It may be significantly younger, but its 340,000 employees mean it is already bigger than the FSB, which is estimated to have somewhere between 200,000 and 290,000 employees.

What is unique about the Rosgvardiya is that it is independent and directly subordinate to Putin. It has powers equivalent of a ministry, meaning that it reports to the President alone. Clues for its purpose can be found in its genesis. Its existence was primarily motivated by two factors: the regional governors who failed to pay federal taxes and needed to be removed, and the increase in street protests which needed to be curtailed. (It’s had more than a few run-ins with Navalny’s demonstrations).

We may surmise, therefore, that Putin intends the Rosgvardiya to act as his personal guarantors of loyalty from other political figures, as well as a means to minimize civil unrest. The fact that Putin appointed his long-time head of personal protection, as well as judo sparring partner, Viktor Zolotov to lead the Rosgvardiya suggests that Putin intends to use the service as an ad hoc personal Praetorian Guard.

VIKTOR ZOLOTOV AND VLADIMIR PUTIN. CREDIT: AP

But perhaps Putin’s intentions for the National Guard are greater still. In spite of its short existence Rosgvardiya’s jurisdiction is surprisingly widespread, and is still growing. Whereas it initially only trained within its own premises, it has been permitted to carry out exercises in Russian cities in preparation for responding to localized threats. It also is likely to receive under its command several factions of special police. The National Guard will also receive duties within the realm of cyber security and intelligence, including the surveillance of social media for terrorist or other extremist agitation. It is not impossible to imagine that their responsibilities within cyber will expand beyond being merely observational.

Suspicions that Putin’s confidence in the FSB is on the wane might explain this transfer of power. He is said to be sceptical of the organisation’s competence after its inability to prevent the St Petersburg metro bombings, the ground it ceded to Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov, its poor intelligence with reference to Ukraine and in particular its failure to anticipate Western sanctions.

The FSB is naturally troubled by this, and sees the National Guard’s augmentation of power as encroaching on a role that had always been reserved for them. Overseeing regional politicians’ security (as well as ensuring they don’t stray too far from the fold) and cyber operations were previously entirely within the FSB’s domain. Until now the FSB has never shared these duties with any other agency.

Although little has been written about this in Western media, the outcome of this conflict between the Rosgvardiya and the FSB play out will be one of the most important things to watch in Putin’s upcoming term. The reason this particular conflict is so important is that this is no usual power struggle.

There has been a good deal of speculation that Putin is seeking to establish a ‘super’ security agency by centralizing a host of smaller agencies under one designation, rumored to be titled the Ministry of State Security (MGB). This would be the second time such a ministry has existed: Stalin oversaw a short-lived but no less feared intelligence agency under that name.

It is not known which existing security services, intelligence agencies, or special forces might be incorporated into the MGB, but it is likely that it would include the heavyweights of Russian security, and its remit would certainly include operations both within the country and without. Should it be instated, it would represent a major battleground on which the conflict between the FSB and the Rosgvardiya will play out. Attaining pole position in such a powerful body would signify a pre-eminent role in the execution of the country’s high-priority security and intelligence questions. And since Putin is the country’s sole decision maker when it comes to foreign policy, being his primary source of intelligence signifies an enormously powerful position.

THE LUBYANKA BUILDING, HOME OF SECURITY SERVICES FROM THE CHEKA TO THE FSB. CREDIT: LE MONDE

This means that there is a possibility that whichever agency receives Putin’s vote of confidence could achieve a snowball effect where their power continues to augment at the detriment of the other. But even if there is no MGB coming, the fallout from this dispute - over what powers the two competing security agencies will contend, how Putin will position himself relative to the two of them, whether one agency will emerge dominant or if they will strike an uneasy balance - will be vital to the future of Russia’s power structures, and is something that should be carefully observed in the following months.

Après Putin, le déluge

In 2008 the Russian presidential term was extended from four to six years, meaning that we will see Putin retain the presidency until 2024. What happens after that, however, is anyone’s guess.

At the end of this term, Putin will be 71 years old. Another term would make him 77. Although his good health may allow him to serve yet another term, the Russian constitution would prevent such an occurrence from happening. Under its articles, no President may serve more than two terms consecutively.

However Putin can circumvent this in one of two ways. The first is to repeat what he did in 2008–2012 and serve as Prime Minister while passing the presidency to a trusted figure, after which he will be eligible for the presidency again. But to repeat such a manoeuvre in the future would mean adding six years to the calculation. Alternatively, he may simply amend the constitution to allow himself to continue to remain president, even after two consecutive terms.

Both of these scenarios are unlikely, and it looks as though Putin will end his presidential run after 2024. Therefore, the question everyone in Russian politics: is gearing towards (but which no one has yet dared broach in a serious way) is who will be next? At present, predicting the next President is a virtually impossible task. Though names like Vaino, Oreshkin, Shoygu and even Medvedev have come up, no one figure stands out as a natural successor. And it is important to remember that when Yeltsin asked Putin to succeed him, Putin was not particularly well known and his appointment was largely unexpected.

Finding a replacement for Putin means finding someone who can fill his shoes. This means that his replacement must not only have to have the same skill in the political game as Putin possesses, but also to be a qualitatively similar leader. The West often decries the authoritarian nature of the Russian administration and hankers for another Gorbachev, but the truth is that Russia is at its most secure with a strongman-type at the helm. Indeed it would seem nearly impossible for such an incomparably vast country to be governed by any other means, without it devolving into a series of increasingly independent federations. Whether one agrees or disagrees with this model is neither here nor there, it is not the one pursued by the Kremlin, nor desired by the Russian people.

Putin understands that this is his appeal. His official campaign slogan makes no bones about it. Sil’nyy Prezident - sil’naya Rossiya (strong President -Strong Russia) is a direct appeal to the Russian image of an idol leader, one who knows how to stand up to foreign powers on behalf of the motherland. This is an electorate whose approval for him increased sharply after his actions in Crimea. It is also an electorate whose patriotism is so great that many Russians will tolerate worse living conditions if it means they are reassured that it enables Russia to stand its ground more competently on the world stage.

A CAMPAIGN BILLBOARD OF PUTIN, INSCRIBED WITH HIS CAMPAIGN SLOGAN. CREDIT: AFP

Putin’s successor must be a figure that is able to fulfil such an image. At present, however, it seems no one is being conditioned to fulfil this role. There is also the second challenge, which is the transition. The end of the Putin era will be a hugely significant even in Russian and world politics. As the system of governance that Putin oversees and manages comes to an end, no small amount of political heavyweights will contend for more powerful positions. Ensuring that the transition to a new leader retains stability in the country will therefore be a vital concern.

There have even been those that theorize that, with challenges like these, Putin may quite simply find it easier to remain President For Life. However, this also seems unlikely. Putin indicated after his victory that he has no desire to “sit until [he’s] a hundred years old.” It seems more likely that we will witness a continued political engagement from Putin, but in a more diminutive role. Possibilities include a place in the State Council or Speaker of the Duma, the Russian parliament. Such positions as a kind of éminence grise would make fewer demands of him, but still allow him to exert influence over the direction of Russia, as well as his own legacy. He would no longer occupy the full limelight by himself, but still be in a position to ease the transition to a new leader and reduce the uncertainty that will accompany his departure as president.

In any case, at this point in time, Putin’s future is up in the air. We can do no more but guess. Therefore any signs of a new figure being groomed to assume presidential responsibilities will be one of the key things to watch out for in the coming years. Indeed it will probably be in the middle to later stages of the upcoming term that we start seeing signs of a replacement. Before then, however, we must wait and see how Putin chooses to deal with the two pressing matters that face him now: the future of the Russian economy, and the future of the security services that form a crucial pillar of the Russian power system.

There is even a possibility that the way he approaches these issues will provide indications of what kind of successor is to come. Will he steer Russia towards Kudrin and orthodox economic liberalism, or towards Titov and the status quo of established interests? Towards Zolotov and greater roles for personal confidants, or towards the FSB and the traditional systems of siloviki power? All such choices signify a specific vision for Russia, and that a possible successor might be representative of that vision. It is clear that we still don’t know much about what the next six years have in store, but what is clear is that the answers that this term brings will be a key force in shaping Russia’s future, as well as Putin’s legacy.