On a recent visit to Iraq, I saw a tale of two countries: one of progress, and one of destruction. Deeper within those stories are lessons on how to deal with global insecurity, terrorism, and an unprecedented global refugee crisis. The common thread was the state of the environment and, more fundamentally, the need for determined climate action.

In southern Iraq, I toured the Mesopotamian marshlands, which form an oasis of fresh water and wildlife in the desert. We were treated to the extraordinary hospitality of local tribal leaders and watched a peaceful sunset from small boats as we floated through the marshes. This being Iraq, I was, of course, also protected by armed guards. But even they were relatively relaxed as we skimmed over the waist-deep waters of Iraq at its safest and most stunning.

For a brief moment, war seemed a world away.

The marshes were almost entirely drained during the Saddam era – through both mismanagement and malice. By the time his regime fell, much of the area was a dust bowl and the population shrank from half a million in the 1950s to a mere 20,000. For more than a decade now we’ve been working with partners, including the national and local government, to bring the marshes back. Today much of the area has recovered and the population has rebounded. This restoration has been so dramatic that the area was recently declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

There are still major challenges. The nearest big city, Basra, has been sweltering under unprecedented summer temperatures, as is the city of Ahvaz just over the border in Iran, where the mercury recently hit an unbearable 129.2F (54C). Some locals say the region may eventually even become unsuitable for human life.

Even at this very sharpest end of global warming, you could feel the region’s sense of achievement and optimism in the air.

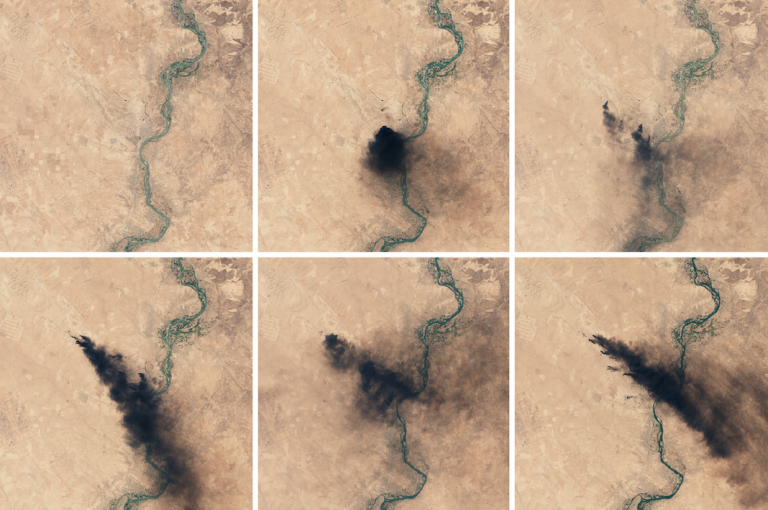

Then I visited the north; including an area recently liberated from the death cult of the so-called Islamic State. Before being ejected from the small town of Qayyarah near Mosul, IS fighters set the nearby oilfields ablaze and torched a local sulphur factory. This act of scorched earth and environmental warfare poisoned the landscape. Thousands of people were treated for respiratory problems, and even the sheep turned black. My visit took place months after the fires were extinguished, but my lungs still burned as I walked around the blackened landscape.

This time, our guards were visibly on edge because this is the other side of Iraq, where danger lurks at every turn and the basics that support human life – security, housing, simple urban infrastructure and even the air we breathe – have been snatched away.

The lessons were clear: the environment can be a source of conflict, a weapon and a driver of war, or a barrier to peace. The opposite is also true: a healthy environment is a key ingredient of a functioning, prosperous society.

Over the past 60 years, at least 40 percent of all internal conflicts have been linked to natural resources.

The illegal timber trade has funded rebel groups in the Central African Republic, while gold and the mineral, coltan, have helped fuel violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and precious stones and deforestation have helped fill the coffers of Afghanistan’s Taliban.

In Syria, a number of environmental factors added to the conditions that have led to today’s ongoing carnage and basic environmental infrastructure has also been decimated. In South Sudan, the civil war has been driven and fuelled by a grab for oilfields and has caused widespread environmental destruction. In Somalia, where I also recently visited, terrorism is financed by a form of environmental rape – the charcoal trade. Together with now-regular severe droughts, this is turning the countryside to dust and sending hundreds of thousands to makeshift camps in towns and cities that can barely accommodate them. Meanwhile, illegal fishing on Somalia’s coastline has driven some communities to destitution, and in some cases, piracy.

The cause-effect equation may not always be entirely linear, but the state of the environment is inextricably linked to global stability.

Not only do conflicts destroy ecosystems, but ruined landscapes can increase the risk and severity of natural disasters that in turn drive mass migration. Increasingly scarce natural resources, sometimes as basic as water, can consequently prolong a war. It’s a vicious cycle that needs to be stopped.

All the more worrying is that all this is happening now, while at the same time we’re also expected to brace for an even more rapidly warming planet – something that we know will make these scenarios worse. That means it’s no longer enough to simply step up the kind of work that has helped southern Iraq’s marshes recover, or repair the damage in northern Iraq, Somalia, and South Sudan. We need concerted global action on climate change: the biggest global environmental threat of them all.

As we push for positive climate action, we’ve made great strides in advancing the argument that this is about seizing an economic opportunity rather than having to shoulder a burden – and I’m happy to say that we’re seeing this thinking take root. Incredible shifts are happening in places like China and India, which, until a short time ago, were cast as big polluters in the making.

Plans for coal-fired power plants are being shelved, and mega solar installations are taking their place. The global energy landscape, from California to Chile to Morocco to Australia, is changing almost beyond recognition because it makes good business sense. This is not just because of the price equation, but because the so-called “positive externalities” – for example, that less smog equals a lower healthcare burden – are now being factored in.

The global security concerns only add to the package of sound arguments behind action and are certainly also in part behind what is driving the visible changes in India and China. Both countries have long-term energy security considerations: in other words, how to find enough energy to power economies of well over a billion people each. As such, harnessing the power of the sun and the wind makes perfect sense.

The Pentagon has also concluded that climate change represents a significant threat. Risks have been identified in areas of US military operations, as well as the thawing Arctic, the South China Sea and even around coastal naval bases and other facilities threatened by extreme weather events.

These connections are why the world agreed on the Sustainable Development Goals as the unifying policy agenda of our time. These 17 objectives serve as a reminder that global development – whether clean energy, climate action, poverty and the health of our oceans – are all connected.

It is, therefore, all the more difficult to understand what drove President Donald Trump to abandon the Paris Agreement. This too, after a campaign centered on jobs, a lower healthcare burden, economic nationalism and tackling global insecurity head-on. Simply put, the decision does not add up, especially when so many nations are talking about raising their own targets.

But one disappointing decision cannot halt global progress. Far from it. Cities and states across the United States have stepped up their commitments, and businesses afforded a seat at the table in the Paris Agreement are also making changes. Google, Apple, Microsoft and many more are embracing a more circular, efficient way of working. Investment funds are now looking into how exposed they are to climate risk, and how equipped companies are to shift to a low-carbon future.

As Secretary-General António Guterres said, simple physics dictates that any vacuum will be filled, and this has been the case for the Paris Agreement. There will not be any renegotiation, and it will continue to go from strength to strength. Almost everyone – from Iraq to Beijing and California to Copenhagen– understands the full spectrum of what is at stake.