The Real Role of the New Mega-Donors: Shaping the Social Agenda

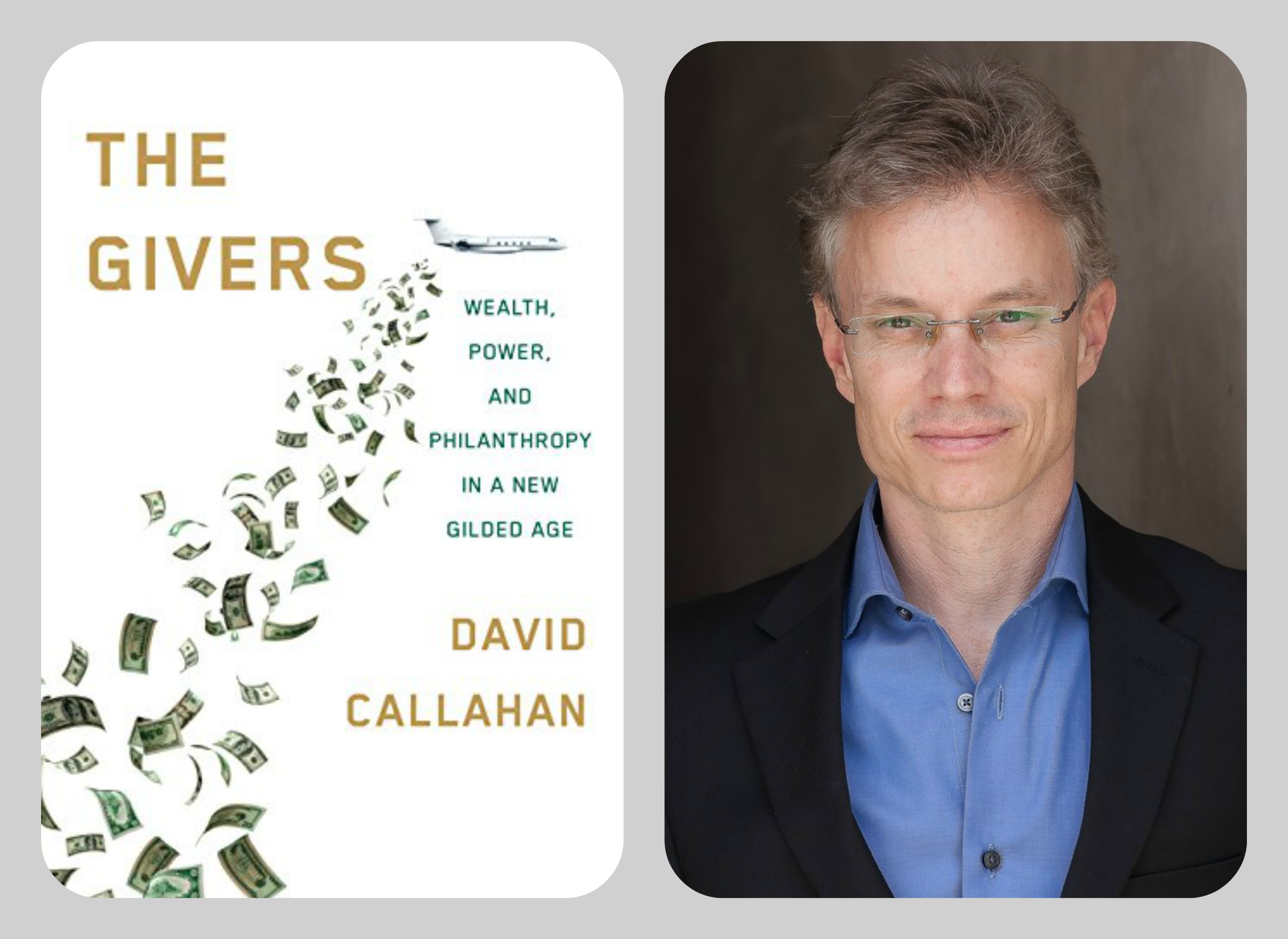

Book Review: The Givers by David Callahan, published by Knopf (April 2017) 352 pages

American philanthropy is in trouble, and more so than you think. First question to ask: Is philanthropy good or bad for society? With the global explosion of philanthropy, the new forms of giving and volunteering, and the rise of social entrepreneurship and impact investing, the issue is more pressing than ever. Nowadays, the soft power of mega-donors has grown so much that in many areas it has displaced governments – even very large ones like the Federal government.

Second question: Is it right for philanthropists to displace government? They do address critical social problems. And they move in where public funds have failed (or are weak).

What is worrying is this: Ultimately, they set the social agenda, not only in the United States but around the world.

Yet, unlike democratic governments and politicians that must face voters, mega-donors are accountable to no one. Their own private views, beliefs and ideologies end up shaping society. They decide what diseases to battle, what kind of schools are needed, what social policies to promote, what research and what artistic trends should be supported.

Is this a fair system in a democracy where all citizens should have a say?

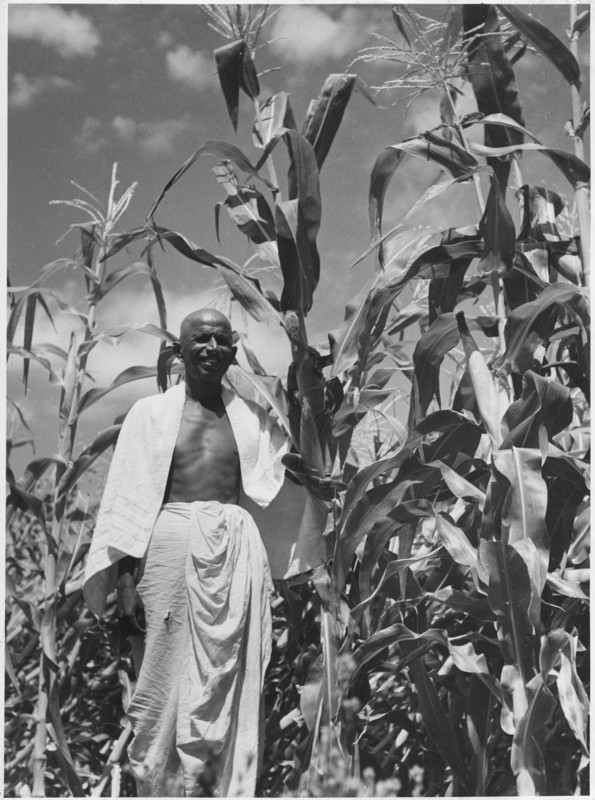

That question is increasingly asked, including in David Callahan’s latest book I am reviewing here. Yet this is not the first time philanthropy arouses suspicion in America. When Rockefeller launched his foundation a hundred years ago, many politicians doubted his good will. As it turned out, the Rockefeller Foundation had a profound impact on the human condition when breakthroughs in the agricultural research programs it had financed in Mexico and India, initiated respectively in 1941 and 1956, laid the foundation for the “green revolution”, so-called because it changed food production for the better, particularly in Asia, helping to solve the recurrent horror of devastating famines.

IN THE PHOTO: Farmer standing in his corn field in Andhra Pradesh, India in 1957 after scientists successfully developed hybrid grains that could resist disease and insects. PHOTO CREDIT: The Rockefeller Foundation

IN THE PHOTO: Farmer standing in his corn field in Andhra Pradesh, India in 1957 after scientists successfully developed hybrid grains that could resist disease and insects. PHOTO CREDIT: The Rockefeller Foundation

Nevertheless, in spite of the successes, countless books and articles continue raising questions, particularly over the past ten years, starting with Philanthrocapitalism: How the Rich Can Save the World, the work of the Economist’s Matthew Bishop and Michael Green. Published in 2008, based on interviews with mega-donors like Bill Gates, it was perhaps the first modern compilation of what philanthropists living today are really up to. Another milestone was reached last year with Philanthropy in Democratic Societies, edited by Stanford political scientist Rob Reich who sees charitable foundations as an “institutional oddity” in a democracy and is concerned that foundations, in spite of their usefulness in supporting innovation – what Warren Buffett famously termed “society’s risk capital” – may be the “voice of plutocracy”.

Among the notable essays in that book, a theory of “disruptive philanthropy” developed by Aaron Horvath and Walter W. Powell, two Stanford sociologists, stood out. Based on the observation that philanthropy often competes with government instead of collaborating with it, it raises deep ethical questions. As Horvath and Powell explained to the Atlantic: “Disruptive philanthropy seeks to shape civic values in the image of funders’ interests and, in lieu of soliciting public input, seeks to influence or change public opinion and demand.”

A classic (and controversial) example that often comes up in this connection is charter schools promoted, inter alia, by the Broad and Gates Foundations. Not everyone agrees that they are an improvement over the existing public education system.

David Callahan’s new book The Givers – Wealth, Power and Philanthropy in a New Gilded Age is the latest arrival on the scene and adds to the debate – philanthropy vs. democracy – carrying it forward with considerable new and updated material. Callahan has done his research for years, he has met many people in the industry, he has uncovered hard-to-find facts about the “opaque” world of philanthropy and the website he has been running, Inside Philanthropy, has been a major source of information ever since it was launched in 2014.

With all this data in hand, Callahan takes us for a roller-coaster ride through the current philanthropy landscape, showing us how living mega-donors wield more power than ever before. And, he warns us, their influence is likely to grow unimpeded as a result of growing income inequality, a trend first magisterially documented by Thomas Piketty in his now famous Capital in the 21st Century.

In short, and to use Callahan’s words, “in many ways, today’s new philanthropy is exciting and inspiring. In other ways, it’s scary and feels profoundly undemocratic.”

Why today’s new philanthropy is exciting

The book starts off by bringing home two stunning truths about our time that, Callahan argues, amount to a paradigm shift:

(1) How utterly rich the ultra-rich have become, the wealth of the Forbes 400 has grown by nearly 2000 percent since 1984; this is indeed a “new gilded age”, mega-donors are more mega than ever, standing on the threshold of a New Age of Philanthropy; as Callahan says, “for all the philanthropy we’ve seen in recent years, it’s nothing compared to what lies ahead.”

(2) How philanthropy has become another means for the ultra-rich to shape society, a means that in some ways is more potent than the corporations and businesses from which their fortunes were made: It is more potent because it gives them more freedom to act; and this is so because there is a total lack of accountability, the ordinary citizen is left out.

To illustrate, Callahan gives us in the opening chapter an unforgettable portrait of Michael Bloomberg, New York’s former mayor and an astonishingly dynamic donor in a dizzyingly broad range of areas, from reproductive health and traffic safety to the environment. And he always makes sure to get the “biggest bang for his buck”, investing in projects with high rates of success – for example, giving $130 million to the Sierra Club plan to shut down coal plants, thus saving an estimated 5,500 lives annually in recent years.

Bloomberg is an iconic model of the new kind of “activist philanthropist”. He may have spent $250 million on his political campaigns to win three terms as mayor, but he has spent several times more than that on charity. On the political spectrum, he stands somewhere in the middle, far from George Soros on the left (scaring conservatives) and the Koch brothers on the right (scaring progressives).

IN THE PHOTO: Michael Bloomberg visits Vietnam on behalf of his private foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies, to promote road safety. PHOTO CREDIT: World Health Organization

IN THE PHOTO: Michael Bloomberg visits Vietnam on behalf of his private foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies, to promote road safety. PHOTO CREDIT: World Health Organization

SEE RELATED ARTICLE: HOW TO STOP CLIMATE CHANGE AND REVERSE GLOBAL WARMING Book Review: Climate of Hope: How Cities, Businesses, and Citizens Can Save the Planet by Michael Bloomberg and Carl Pope

To get a grip on the sheer size of this paradigm shift, it helps to compare historic American foundations with the Gates Foundation. Combined with the Gates Trust to which Warren Buffett contributes, it currently holds some $65 billion in assets: That is over four times as large as the Ford Foundation ($12.5 b) and 16 times the Rockefeller Foundation ($4.2 b). And remember, both the Ford and Rockefeller foundations have shaped American philanthropy through the 20th century. In Rob Reich’s words: “What Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller were to the early twentieth century, Bill Gates and Warren Buffett are to the early twenty-first century.”

Moreover, the Gates Foundation has already given away more than $37 billion in a wide range of worthy causes, from fighting malaria and the AIDS epidemic in Africa to strengthening education. And there’s much more to come, perhaps as much as $150 billion to distribute in future since the foundation endowment is to be fully spent twenty years after the death of the last founder.

IN THE PHOTO: Medical field worker talks with residents of Durban, South Africa about microbicides on behalf of the Gates Foundation. PHOTO CREDIT: Gates Foundation

IN THE PHOTO: Medical field worker talks with residents of Durban, South Africa about microbicides on behalf of the Gates Foundation. PHOTO CREDIT: Gates Foundation

This particular feature, a foundation with a sunset clause, is however relatively rare. Many are set up to last forever. The size and permanence of this new style of giving suggest – and there’s some early evidence too – that a new power elite is in the making. The families of mega-donors have a greater chance to leave a legacy and endure through their foundations’ works than through mere inheritance.

Why it is scary

Philanthropy feels undemocratic because of the lack of accountability.

Mega-donors make mistakes – for example in breaking up a school system in smaller units that don’t necessarily work or is not what parents and teachers want – but they don’t pay for their mistakes. They merely stop the programs that don’t work. Or at best, they operate in-course corrections provided they pay attention to what their beneficiaries tell them, the case, for example, of the Chicago Community Trust with its “On the Table” initiative and several others.

The other truth Callahan hammers home is the lack of transparency.

Most of the time, we don’t know who are behind the donations. As Callahan grimly puts it, “nonprofit laws allow rivers of money to sluice through society in opaque ways.” But the problems are not new and American nonprofit laws have existed over a hundred years.

But something happened in 2010, a year that proved to be a major turning point for the wealthy in many ways. It was the year that Warren Buffett and the Gateses launched the Giving Pledge, starting with some forty families committed to giving away at least half of their wealth to philanthropy; today the Pledge has more than 150 billionaires signed up for a total of some $365 billion.

2010 was also the year the Supreme Court handed down its pivotal Citizens United decision that sidelined ordinary citizens, giving an unparalleled voice to corporate America and changing the way political campaigns are run – and possibly changing for good what “democracy” means in America.

SEE RELATED ARTICLE: UNCHAIN AMERICA Book Review: “Captured: The Corporate Infiltration of American Democracy” by Sheldon Whitehouse

That year the Republicans took control of Congress and a majority of state houses, setting out to downsize Big Government. In 2014, even though Obama had won a second term, Republicans confirmed their lead. Eventually, long-term budget cuts totaling some $3 trillion affected every area of government “discretionary spending”, from scientific research to Head Start to environmental protection. Forty years ago, that spending stood around 5% of GDP, today it is around 2.2 percent and with the upcoming Trump budget, it is likely to shrink even more.

At that level, charitable giving will soon match it. While it is true that is has “remained stuck for decades” at around 2 percent of GDP, it is likely, if Callahan’s reading of the situation is right, to grow much faster in future, as the new wave of giving by wealthy donors speeds up with the arrival on the scene of the new tech giants and a slew of newly minted post-2008 Wall Streeters.

This new wave, as Callahan abundantly illustrates, has changed the political game. Unlike 20th century foundations, the new philanthropy is “activist”, seeking to shape the policy debate in Washington through ideologically driven think tanks. Among them, the Heritage Foundation stands out, the first to openly provide a sitting American President (Reagan) with a blueprint for his policies. The pages in Callahan’s book that describe the rise of think tanks, in particular the American Enterprise Institute and the Peterson Institute, make for fascinating, if scary, reading. As he notes, donors on the left were slow to rise to the challenge – largely because progressive ideas were normally the province of universities and there seemed to be no need to fund think tanks.

IN THE PHOTO: Think tank leaders from 20 countries meet in Istanbul for the Think-20 (T20) launch. PHOTO CREDIT: T20 Turkey

IN THE PHOTO: Think tank leaders from 20 countries meet in Istanbul for the Think-20 (T20) launch. PHOTO CREDIT: T20 Turkey

Perhaps the most shocking chapter is the one about “super-citizens” – at least for anyone committed to democratic ideals. The list of super-citizens is long and Callahan starts it off with the media mogul Barry Diller and his wife, the fashion designer Diane von Furstenberg, and their pet project, the new island park to be built in Chelsea, on Pier 54, on the Hudson River off the West Side of Manhattan. Costing £170 million, Diller is to pick up most of the tab, leaving only $40 million to the city. But that is a lot for a city that lacks funds for public parks, with hundreds of parks in urgent need of maintenance and upgrading. Moreover, there was an agreement to turn over park management to the donors.

Critics were quick to question why a new park should be planned for one of Manhattan’s wealthiest areas that already had two major parks, the Hudson River and the High Line (to which Diller had also contributed); and why the city should give up its park management responsibilities. As Callahan notes: “Welcome to the era of ‘super-citizens’, where philanthropists are literally reshaping the geography of our cities.”

The “reshaping” is not necessarily bad or self-serving. Sometimes it is very much for the better: as an example, Callahan points to George Kaiser in Tulsa who has “pumped millions into building state-of-the-arts early education centers that serve low-income children, and given even more help to set up health clinics in schools and public housing projects”.

PHOTO CREDIT: RDG Planning and Design

PHOTO CREDIT: RDG Planning and Design

The problem is simply that ordinary citizens have no say.

And this is happening for a simple reason: “private donors – who are both more numerous and more wealthy – are stepping into a vacuum created by the decline of the public sector. New York Mayor Bill de Blasio may not be able to find much money for big new projects, but Barry Diller can.”

Let’s be clear: Callahan has not turned his book into an attack on the new philanthropy. He takes care to maintain a balanced approach, reporting on both successes and failures, stepping away from any judgment, repeatedly reminding his reader that mega-donors span the whole political range from left to right, from progressive Democrats to deeply conservative libertarians.

To me, some of the more interesting parts of this book are those that depict the long slide of America towards an uncompromising libertarian Ayn Rand ideology, sustained by think tanks lavishly funded by conservative philanthropists – a slide that began in the 1980s and that has brought us where we are now, with Donald Trump in the White House. Yet Callahan is adamant: “There is no plutocratic plot behind today’s big philanthropy – at least not that I’ve uncovered. Very few of the donors are doing anything sinister. You may or may not agree with the ends they seek, but their means reflect a feature of our society that has made it better and stronger since Tocqueville’s day.”

But, he acknowledges, “we still have a problem”. And, he argues, “now is a good moment to reform philanthropy so that it is more aligned with American values – and especially the egalitarian ethos so core to our national identity.”

How to make philanthropy more democratic

In the last chapter, Callahan comes up with a couple of simple solutions to “fix” philanthropy and make is more accountable in a democratic society, a laudable objective that many philanthropists themselves are likely to want to follow. He calls for more transparency – foundations should publish more information about where their money is going – so that foundations are more accountable. And he suggests a careful re-writing of the IRS rules to avoid an overlap of tax categories, so that gifts that have a clear political purpose do not escape taxing as they do now.

But going beyond a tax fix, the question appears very complex as it is in fact tied up with the role one would want for the public sector. Should “public goods” be left in the hands of the Federal or State governments or transferred to the private sector?

The cost efficiency of the private sector is supposed to be superior, though that is debatable (there is recent contrary evidence). On the other hand, government accountability to voters may not be a benefit in those cases where solutions don’t appeal (or are not understood) by the majority of citizens. They will be by-passed, even if they are in fact better. In short, government may not be so “good at exploring new ideas and taking risks”.

Bill Gates has famously argued that his foundation is in fact “an R&D shop that engages in experiments that governments can’t or won’t fund”, and is thus expanding the “pool of ideas available to decision-makers”. And it’s only a “pool of ideas”: Gates insists that the final decision to scale up experiments is in the hands of government.

Moreover, it’s not a “pool of ideas” that is de-linked from ordinary citizens. As Priscilla Chan told Callahan: “Mark and I aren’t in some ivory tower making up all these strategies on our own. We are deeply connected to experts. We are in touch with the front lines…”

Yet Callahan makes the case that the wealthy have a different set of ideas and values than the general public: They are “more fiscally conservative and socially liberal than the population as a whole. They have a stronger belief in market solutions and technocratic fixes, and don’t share the public’s rising concern that the system is ‘rigged’.”

Maybe. If we believe they do more damage than good because of those beliefs, then we should put an end to a tax system that benefits them. After all, the tax exemptions awarded to the no-profit industry come with a cost to taxpayers. The US Treasury has estimated that cost would climb to some $740 billion over the next decade, a huge amount. If, on the other hand, we believe they are indispensable for pluralism and giving voice to issues that otherwise would never see the light of day, then we should accept the status quo (and the tax loss).

Perhaps the way out of this quandary is simply a series of minor fixes as Callahan suggests: (1) to the tax system to slow down charitable giving with an overt political agenda; and (2) to transparency rules to monitor more closely who is giving what to whom, thus keeping the general public informed of what directions philanthropy is taking. Private foundations report grants in their tax returns, but that is not enough. It can take several years before the information is available to the public. And donor-advised funds should, says Callahan, also be required to disclose their donors just as private foundations must.

In short, as Callahan grimly notes, “we are flying blind into the biggest giving spree in history […] It doesn’t help matters that we also can’t answer basic questions about the efficiency of the charitable sector.” And he notes that the job of monitoring is entrusted to a weakened IRS: reviewing some 60,000 nonprofit applications every year is done by “just 200 low-level employees at a regional IRS office in Cincinnati.” And of course, this weak oversight “helps explain a steady stream of charity fraud cases.”

Callahan’s call for “stronger watchdogs” makes sense. He suggests establishing a new US federal office of charitable affairs that would provide “expanded regulatory oversight” and “help orchestrate partnerships between government and philanthropy”.

IN THE PHOTO: Public concern about the link between government and philanthropy rises. PHOTO CREDIT: Sierra Club

IN THE PHOTO: Public concern about the link between government and philanthropy rises. PHOTO CREDIT: Sierra Club

I believe that’s a good idea but I doubt that it is politically feasible. Yet, if the politics change in America, it may happen in future. As Callahan reminds us, “if this sector doesn’t deliver more to the least fortunate, it may be only a matter of time before the tax breaks that help fuel it will come under attack”.

Perhaps, rather than launching a new government facility, we could look to strengthen the donor industry’s own oversight capacities. Non-profits will surely need to make a case for themselves.

Something is stirring in the industry. The National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, established in 1976, has often made the point that “too few charitable dollars go to alleviating poverty or fighting injustice”. And an increasing number of outfits, among them the Fund for Shared Insight launched in 2014 and backed by over half-a-dozen foundations, are designed to help non-profits to better listen to the people they seek to help.

But more is needed. It is not only a matter of listening to the beneficiaries, but of figuring out what the whole philanthropy landscape looks like, what is needed by whom, and who is working where and with what results.

The point is to avoid duplication and get a sense of where we are going with this giving spree. Isn’t that something the Giving Pledge team could do? Once the landscape is mapped out, we could at last engage in a serious discussion of what is really needed to preserve both philanthropy and democracy.

IN THE PHOTO: Farmer standing in his corn field in Andhra Pradesh, India in 1957 after scientists successfully developed hybrid grains that could resist disease and insects. PHOTO CREDIT: The Rockefeller Foundation

IN THE PHOTO: Farmer standing in his corn field in Andhra Pradesh, India in 1957 after scientists successfully developed hybrid grains that could resist disease and insects. PHOTO CREDIT: The Rockefeller Foundation IN THE PHOTO: Michael Bloomberg visits Vietnam on behalf of his private foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies, to promote road safety. PHOTO CREDIT: World Health Organization

IN THE PHOTO: Michael Bloomberg visits Vietnam on behalf of his private foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies, to promote road safety. PHOTO CREDIT: World Health Organization IN THE PHOTO: Medical field worker talks with residents of Durban, South Africa about microbicides on behalf of the Gates Foundation. PHOTO CREDIT: Gates Foundation

IN THE PHOTO: Medical field worker talks with residents of Durban, South Africa about microbicides on behalf of the Gates Foundation. PHOTO CREDIT: Gates Foundation IN THE PHOTO: Think tank leaders from 20 countries meet in Istanbul for the Think-20 (T20) launch. PHOTO CREDIT: T20 Turkey

IN THE PHOTO: Think tank leaders from 20 countries meet in Istanbul for the Think-20 (T20) launch. PHOTO CREDIT: T20 Turkey PHOTO CREDIT: RDG Planning and Design

PHOTO CREDIT: RDG Planning and Design IN THE PHOTO: Public concern about the link between government and philanthropy rises. PHOTO CREDIT: Sierra Club

IN THE PHOTO: Public concern about the link between government and philanthropy rises. PHOTO CREDIT: Sierra Club