A Conversation with Michael New, World Expert on Freshwater Prawn Farming and Founder of Aquaculture without Frontiers (AwF)

For a long time, aquaculture was the foster child of agriculture, but now it has come of age: output has more than tripled over the past 20 years, making it the world’s fastest-growing food producing sector.

After the conquest of land, farming is conquering water, a much greater challenge.

With a production close to 80 million tons annually, fish farming provides the world with 17 percent of its animal protein. The lion’s share of aquaculture production, some 90 percent, comes from developing countries, and while most fish farms are in Asia, aquaculture’s highest growth rates have of late been in Africa and South and Central America.

The Fish Farming Revolution

Developing countries get more revenue from farmed fish exports than from meat, tobacco, rice and sugar combined. China however, remains the big player, exporting over twice as much in value terms as Norway that clocks in second.

But rankings are shifting with new entrants. In 2014, Thailand, historically the world’s third-largest exporter of fish products, was surpassed by Vietnam, thanks to the rapid market acceptance of its pangasius production, a freshwater white fish that competes successfully with sea-based species such as cod and the freshwater channel catfish produced in the Americas.

Fish farming is fast becoming big business and fish trade requires regulation more than ever to reassure consumers. According to Audun Lem, Deputy-Director in FAO’s Fisheries Policy Division, one reason aquaculture has surged ahead of open-sea fishing is that its production methods are typically “far less seasonal and volatile.” This allows for easier access to insurance or credit – for example, there are now salmon futures – and even “tailored solutions” such as the production of fattier salmon better adapted for smoking.

Photo: (above) Pangasius harvest – Vietnam. Source: Vietnam Pangasius Association.

As aquaculture production becomes more reliable, longer-term investmentS can be made in a number of innovative techniques such as selective breeding, cold-storage facilities and methods to minimize fish waste. This opens the way for “fewer but larger operators,” a process well advanced with species such as marine shrimp, tilapia, Atlantic salmon and European sea bass and bream.

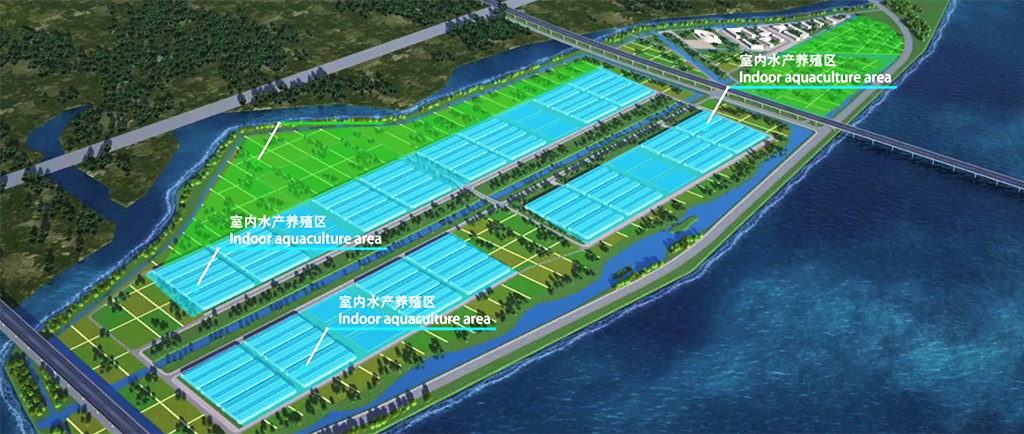

An example of one such large operator is Sino Agro Food, inc., an American company operating in China. It is currently establishing mega farms in China to meet the demands of the Chinese middle class, estimated to be around 500-600 million; one project in particular, in Zhongshan, is unprecedented in size and scope, the largest fish farm in the world, covering some 600 acres and using the most advanced water-recycling technology.

In the Photo: Zhongshan Mega Farm. Photo Credit: Sino Agrofood

It is currently establishing mega farms China to meet the demands of the Chinese middle class, estimated to be around 500-600 million. One project in particular, in Zhongshan, is unprecedented in size and scope, the largest fish farm in the world, covering some 600 acres and using the most advanced water-recycling technology.

This video explains it:

In short, China not only started small-scale fish farming in rural areas over two thousand years ago, but it is now at the head of the aquaculture revolution, embracing the most advanced fish farming techniques in the world, and on a scale never seen before.

Aquaculture and the Poor

Is farmed fish a solution for hunger, the quick way to achieve the United Nations Agenda 2030, in particular, two of the 17 global goals, SDG#1 (no poverty) and SDG#2 (zero hunger)?

In the Photo: Small scale aquaculture: A 22-member women’s agriculture group in Machakos, Kenya runs a fish pond enterprise. Photo Credit: Wikimedia

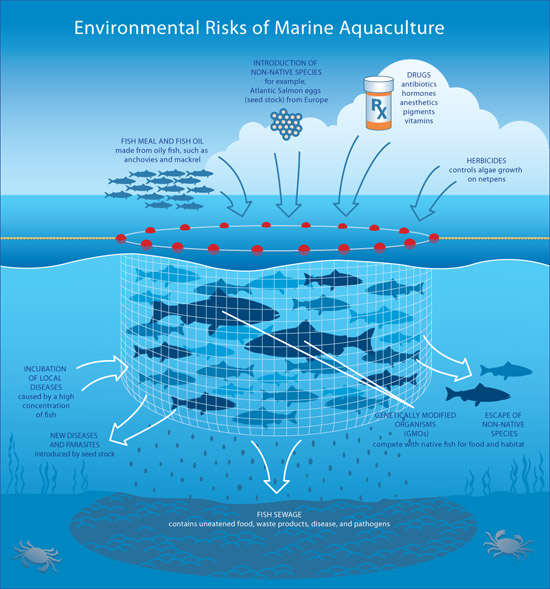

The answer is not straightforward since environmentalists have for a long time accused fish farming of water pollution and destruction of certain fragile environments, particularly mangroves and wild fish habitats – thus working against SDG#14 (life below water, with targets to “conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources”).

Related article: “OVERFISHING, CLIMATE CHANGE AND HUNGER”

The promise of aquaculture was further clouded by a famous essay written by a series of respected aquaculture researchers in 2000, known as the “Naylor report,” from the name of its lead author Rosamond L. Naylor.

That paper argued that some types of aquaculture, far from relieving pressure on ocean fisheries, increased it because farming carnivorous species requires large inputs of wild fish for feed, grimly concluding that “if the growing aquaculture industry is to sustain its contribution to world fish supplies, it must reduce wild fish inputs in feed and adopt more ecologically sound management practices.”

Photo: Wikipedia Mariculture; Credit: Dr. George Pararas-Carayannis

This put the onus of ecology squarely on fish producers, large and small.

While large producers may be able to address the added demands for “ecologically sound management,” small producers with difficulties to access both technical information and financial resources are likely to face real problems to adapt and risk being left behind.

The Birth of Aquaculture without Frontiers

These are the problems Aquaculture without Frontiers (AwF) was intended to address. A unique NGO focused on developing small-scale sustainable aquaculture to help the rural poor, AwF did not seek to promote aquaculture in isolation. In the AwF vision, aquaculture is but one component of integrated rural and coastal development plans, and of broader strategies to alleviate poverty.

AwF founder, Michael B. New, introduced his ideas in a well-received keynote address at the annual meeting of the World Aquaculture Society in 2003 when he was President of the European Aquaculture Society (address available here on Thingser). At that point in his life, Mr. New, OBE, a graduate of Imperial College London, with nearly 40 years of experience in aquaculture and animal feeds, had made major contributions to the expansion of freshwater prawn farming around the world and was eager to put his expertise at the service of the rural poor. He had served at FAO as a senior staff member and worked as a high-level consultant at several international organizations, including the Asian Development Bank and the European Commission. Today, he remains a highly respected editor and published author, with nearly 150 technical manuals, scientific papers and popular articles on aquaculture to his name.

AwF, launched in 2004 on the heels of the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami disaster, immediately raised funds and within months was active on the ground, with, inter alia, a flagship project in a tsunami-devastated area of Aceh, Indonesia, to help small farmers rebuild their fish ponds.

Photo: Rebuilding after the 2004 Tsunami in Aceh, Indonesia, AwF project (oil painting by Claude, M. New property)

By 2008, AwF had 130 volunteers and was running a number of low-cost projects in Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Malawi and Thailand, as explained in its newsletters.

Among major findings:

(1) The strategy adopted by AwF for project implementation – in the light of limited project budgets – largely relied on the multiplying effect of training: farmers trained by the project taught new farmers and encourage each other in various areas concerning fish production as well as the marketing of fish – thus achieving self-perpetuating development.

(2) Farmers revealed that overall pond productivity was better in integrated aquaculture-agriculture (IAA) and they found the IAA technology easy to adopt.

Examples of Integrated Aquaculture-Agriculture (IAA)

Integrated backyard pig-fish culture in the Philippines:

Credit: FAO

A model of upland integrated farming system in Vietnam:

Credit: FAO

For a full mindmap behind this article with articles, videos, and documents see #farmingwater

In 2015, after over a decade of voluntary service, Mr. New left AwF for others to develop; he continues to write and dispense much sought-after advice. He recently talked to Impakter describing his experience and outlining future challenges and prospects for aquaculture; here are highlights of our conversation, edited for brevity.

In the light of your long experience, can you tell us about aquaculture, what are the challenges?

Michael New: Aquaculture is much more complex than the farming of traditional terrestrial species, particularly because it is conducted in water, not just with water.

This makes it especially prone to problems associated with water quality, climatic events and climatic change. It must be practised in enclosures of some kind – ponds, cages placed in freshwater or marine locations, tanks or raceways with flow-through water, or tanks within outdoor or indoor environmentally-controlled locations. Animal losses can occur due to flooding or to typhoons in coastal locations. All these factors probably make aquaculture more risky than other animal production; sudden losses, sometimes total, can occur due to the events listed above and to disease. However, unlike the case with terrestrial animals, I cannot think of any case of disease transfer from aquatic animals to humans.

You say aquaculture is farming conducted in water and with water, does that lead to over-use of water?

M.N.: It’s not a major consumer of water, and that’s a plus for aquaculture. The water can generally be reused, either for further aquaculture, or for agricultural purposes like irrigation, although there are losses of water due to evaporation, particularly in tropical and desert locations. Multi-use of water is practiced. For example, more than one species can be grown together if they occupy different environmental niches: you can have polyculture – different species grown together in the same enclosure, such as a pond – and co-culture – one species grown in a cage within a pond containing the other species. Other types of the multiple use of water in aquaculture include rice-fish culture; rice-prawn culture; rice-prawn-fish culture; fish culture combined with aquaponics, etc.

Fish is such a mysterious animal, does that pose a special challenge?

M.N.: Yes, and that’s another reason why I say that aquaculture is more complex than other types of farming: such a wide range of species are farmed, each with its own demanding specific environmental and rearing conditions. This poses many technical challenges. Aquaculture is practised in freshwater, brackish water and seawater. There are broad categories, of course – macroalgae, molluscs, fish, and crustaceans – but within each there are huge numbers of individual species farmed. Thus there are complexities not just in the farming of so many species but in their distribution, storage and marketing. In terrestrial animal farming although many different varieties exist, there are only a few major types of animals farmed – pigs, cattle, sheep, poultry…

Aquaculture has often been criticized by environmentalists – notably in the Naylor paper that argued that farming carnivorous species required large supplies of wild fish feed. But that was fifteen years ago, is it still a problem today?

M.N.: This problem is being tackled. Even at the time of the Naylor paper, marine ingredients were also included in feeds for terrestrial animal production. Their use in aquaculture has not increased the total exploitation of fisheries for fish meal/oil production; it is just that aquaculture has been using a larger proportion of a static supply. Even this is rapidly changing now; huge research and production efforts by both public and private bodies have been successfully made toward the substitution of fish meal by vegetable and microbial proteins. The use of insect protein in aquafeeds is also possible in the future.

However, care is needed to ensure that the nutritional value/composition of the final aquaculture product is not compromised. Another plus for aquaculture is that fish are much more efficient users of feed (better feed conversion ratios) than terrestrial animals.

Another criticism of tropical coastal aquaculture was mangrove destruction…For example, a 1997 Asian Institute of Technology study found that over half of the mangroves in Thailand were destroyed by human activity – of which 32% was caused by shrimp farming.

N.M.: Even in 1997, shrimp farming was not the main culprit. Since then this criticism has subsided; it was pointed out that other activities, like logging, industrial and housing/tourist developments, etc. were worse than aquaculture. Also, new shrimp farms are now located behind the mangrove belt.

What about the use of antibiotics in aquaculture?

M.N.: It has certainly evoked considerable criticism. But salmon farming has largely cleaned up its act since the days when the participants in a World Aquaculture Society conference in Seattle were greeted with street demonstrations organized by PETA using banners proclaiming SALMON DON’T DO DRUGS.

However, antibiotic use continues, particularly in some forms of shrimp farming, and there have been a number of bans against imports from certain locations by the major importing countries (USA, Europe, and Japan).

Here again, considerable efforts are being made by the industry to improve, particularly through the use of probiotics. One can only point out that antibiotics are also used in the farming of terrestrial animals; this practice is also, rightly, under fire.

In the Photo (above): Protesters near the American Gold Seafood Company, Seattle 2013 Credit: Living Humane

And now I’m coming to the use of GMO’s, certainly more of a concern in Europe than in America…

M.N.: Numerous concerns remain about the potential use of GMO fish, although GMO salmon has just been given federal approval in the USA. While some of these concerns have proved unfounded, like GMO fish might cause cancer, there are questions about what might happen if GMO fish escaped in the wild. Perhaps what is really unsettling is humanity’s newfound ability to reshape nature and that goes far beyond aquaculture.

In the Photo: Eating 2.0: GM salmon vs. farmed salmon. (Source)

So the image of aquaculture among Western consumers may not be as bad as it used to be, do you see an improvement?

M.N.: The public perception of aquaculture is, in my opinion, markedly improving. A decade or two ago, most people did not know what aquaculture was. Now, increasingly, the public is regarding it as just another form of animal farming. There have been many efforts to improve the image of aquaculture which have helped in this respect – the development of Best Management Practices; Certification, etc. However, my personal view is that the public may be confused by the plethora of certification systems in use.

Yet we often buy farmed fish, and this is not surprising since it is cheaper than wild fish and more available as aquaculture production expands.

M.N.: The public are also becoming aware that production from capture fisheries has peaked and remains fairly static. Thus, with an expanding global population, we cannot maintain, let alone increase existing per capita fish consumption. To increase food supplies and enhance health for the poor, there is no way except through aquaculture

You expect fish farming to be able to provide (at least in part) the extra food needed for our growing world population?

M.N.: A major problem dogging the further expansion of aquaculture in many countries is over-regulation. Production in Europe and the USA is not expanding as it should. Thus – reliance on imports.

What was wrong with aquaculture development aid, what were the challenges, what needed to be done?

M.N.: While FAO’s contribution to the expansion of aquaculture in developing countries is now mainly confined to the dissemination of guidelines and technical information through publications, seminars, workshops, etc., development projects have been conducted by the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, etc. These raised fundamental questions such as:

- Should projects be designed to expand industrial aquaculture for well-heeled domestic or foreign consumers or should they concentrate on food production for the poor? Perhaps both, but the emphasis in my opinion should be on the latter. Industrial aquaculture development could be left to the private sector;

- Large-scale aquaculture can create jobs but may also displace rural and coastal communities and their other farming and fisheries activities;

- Coastal conflicts may be due to aquaculture, e.g. competition with capture fishers, the tourist industry, land and water environment;

- Sustainability: it is a function of the recipients’ ability to maintain facilities and equipment after project aid is withdrawn;

- Value chain: Do projects only concentrate on aquaculture production, when there is also a real need to improve transportation, processing, storage and distribution? This applies to fishery products generally, not just aquaculture.

In 2003, you decided to create AwF to address the problems of the poor and promote small-scale aquaculture. Looking back, what were the greatest achievements of AwF under your watch?

M.N.: That is very difficult to say. I suppose they included alerting worldwide scientists, suppliers and producers to poverty and hunger in developing countries; establishing a group of several hundred active volunteers; launching some successful projects, like the one in Nepal with the Asian Institute of Technology (AIT) that was rolled out to a wider area by the Nepalese government; assisting farmers following the 2004 tsunami, not only in Aceh (Indonesia) but also in India. I think that our newsletter of January 2008, when we were at our most active, will give you a taste of our pride in what we were doing.

In your opinion, what would it take to bring aquaculture into the 21st century, what remains to be done?

M.N.: Aquaculture in developing countries is already being ‘brought into the 21st century’ in the sense that large corporations have been forming and continue to establish very large farms to supply both domestic and export markets.

Sometimes these corporations are local; an example is the Charoen Pokphand Group in Thailand, which operates marine shrimp farms and/or aquafeed factories in many countries, from India to Indonesia. A further example is in China – Sino Agro Foods, which is building a huge RAS farm for freshwater prawn production.

In other cases they are joint ventures with western organizations, principally feedstuff manufacturers that make aquafeeds. Nutreco (Dutch) is one example, Cargill (American) is another, which has just taken over Ewos (Norwegian). All these ventures are farming or supplying aquaculture products (principally salmon and shrimp) to ‘developing’ countries for luxury markets, both domestic and export.

What about small farmers, how are they faring compared to the big operators?

M.N.: Smaller local farms and cooperatives are also producing for export but there is a real risk that they may be left behind. I’d like to recall here the original targets for AwF: to enable poor families who live on small plots of land with access to water to grow fish for their family consumption and the sale of excess production to neighbors. These targets are still valid today, particularly considering the changes the industry faces and the shift towards ever larger operators.

In the drive to satisfy the appetites of the wealthy, the rural poor should not be forgotten.

Recommended reading: “RESPONSIBLE AQUACULTURE: A SPECIAL CHALLENGE FOR DEVELOPING COUNTRIES“

_ _