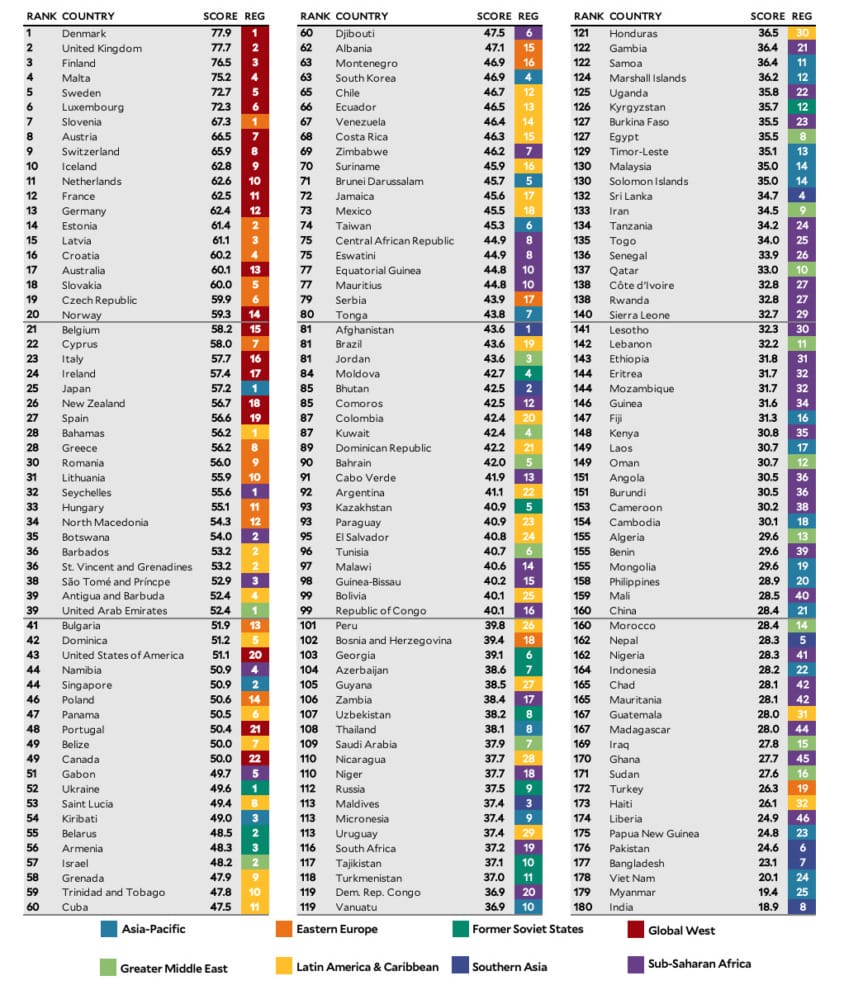

Published every two years by researchers from Yale and Columbia, the Environmental Performance Index (EPI) provides a summary of the sustainability statistics of 180 countries. This year’s results reveal that only Denmark, Great Britain, Botswana, and Namibia are on paths to achieving net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050.

What is the EPI?

The most comprehensive global environmental analysis ever published, this year’s EPI leverages 40 performance indicators across 11 issue categories, which are then aggregated into climate change performance, environmental health, and ecosystem vitality.

The EPI researchers transform raw environmental data into indicators that place countries on a 0–100 scale. The EPI also provides scorecards of climate “leaders” and “laggards”, as well as practical guidance for a more sustainable future.

The individual metrics are wide-ranging, from “air quality” to “wetland loss,” and the results help countries refine policy agendas, facilitate stakeholder communications, and boost environmental investment.

The EPI aims to hold countries accountable for their sustainability goals

To avoid the most catastrophic climate change risks, scientists have said that the world needs zero emissions from fossil fuels and no deforestation by 2050.

“If the ultimate goal is zero emissions, then the metric we really care about is how quickly countries can get to zero,” explains Kate Larsen, director at energy research and consulting firm Rhodium Group.

The 2015 Paris Climate Agreement set out a global framework to avoid dangerous climate change by limiting global warming first to well below 2°C, and then to 1.5°C. However, the 2021 IPCC report, published just before COP26 in Glasgow this autumn, has warned that based on the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) agreed to in the Paris Climate Agreement, the world was headed towards a 2.7° increase in global average temperatures by the end of the century.

Today’s #IPCC report is a stark reminder of the threat climate change poses to us all

It shows the changes we are seeing are affecting us much sooner and are much greater than previously thought

We cannot fail to prepare now (1/2)

— Rt Hon Lord Alok Sharma (@AlokSharma_RDG) February 28, 2022

This reflects the serious concern that world leaders have little time to make a climate breakthrough.

In response, the 2022 EPI includes a projected emissions tool to show proximity to net-zero GHG emissions by 2050 in accordance with these targets. This metric aims to help policymakers, businesses, the media and NGOs evaluate national policies, making the EPI essential for pressuring leaders for more ambitious environmental decision-making.

The Results: Who came out on top?

This year, as in 2020, Denmark tops the EPI rankings. This is based on a strong performance on most of the EPI indicators, with notable success in clean energy and sustainable agriculture. Denmark is already well on its way to reaching these targets. The government made a binding commitment to reduce emissions 70% below 1990 levels by 2030, and ⅔ of the country’s electricity comes from clean energy.

The United Kingdom and Finland placed 2nd and 3rd, earning high scores for slashing greenhouse gas emissions in recent years. Overall, the 2010-2019 trajectories show that only Denmark and the UK were on path to eliminating emissions by 2050.

Namibia and Botswana also did well in the emissions section, but EPI researchers have included these results “with caveats” as the emissions of these two countries were minimal to begin with and as it is uncertain how they will develop as their economies grow.

In the overall rankings, countries with expectations for their climate performance such as Sweden, France, Germany, Italy and Japan all ranked within the top 25 countries, with most improving their scores compared to the 2020 EPI.

Many countries were revealed to have acted insufficiently to cut their GHG emissions and address policymaking concerns, such as India, China, Turkey and Pakistan.

A tumble for the US, concerns over India and China

The US placed 43rd overall with a score of 51.1/100, which represents a fall from the 24th place and a 69.3/100 score in the 2020 EPI rankings.

The US is lagging behind its peers as a result of the rollback on climate policy and environmental protections during the Trump Administration. Whilst other developed countries enacted policies to reduce GHG emissions, Trump withdrew the US from the Paris Climate Agreement and weakened methane emissions rules. These moves meant the US plummeted to the 101st place on climate metrics, behind every wealthy western democracy (apart from Canada, which came 142nd), even though US emissions did fall considerably over the full 10-year period during the Obama administration’s emissions regulations.

Because these results are based on data through 2019, the figures do not reflect Biden’s announcement this year that the US would cut greenhouse gas emissions 50% to 52% below 2005 levels by 2030 and his infrastructure proposal for clean energy and electric vehicles.

Climate change is already ravaging the world. We know that none of us can escape the worst that’s yet to come if we fail to seize this moment.pic.twitter.com/g6ESsvqV5b

— Joe Biden (@JoeBiden) November 2, 2021

Although this may seem somewhat ambitious, they are not as ambitious as the UK or EU’s climate targets. In addition, America’s pace of reduction has been insufficient considering how high its initial emissions were.

However, the Biden administration may not even be able to meet its 2030 targets as its pledges, unlike those in the EU and the UK, are not enshrined in law. Biden’s aims are also marred by Republicans who believe that targets are too ambitious.

Senator of Wyoming John Barrasso said that Biden’s “drastic” and “damaging” targets would punish the US economy while “America’s adversaries like China and Russia continue to increase emissions at will.” Finally, Biden’s 2024 re-election is also uncertain.

If EPI 2022 projections are accurate, at this rate the US will be the third largest emitter by 2050, behind China and India, which came last in the index and which, together with Russia, will account for over 50% of global greenhouse gas emissions in 2050 if current trends hold.

China, the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases, has pledged that its emissions will peak by around 2030, and that it will then aim to get down to net zero emissions by 2060. China’s targets also include curbing hydrofluorocarbon use and getting a quarter of its energy from low-carbon sources.

If these targets are met, the Rhodium Group states that China’s emissions could level off close to current levels by the end of the decade, but China has not committed to specific cuts before 2030. The country’s vice foreign minister Le Yucheng argued last week that as China industrialised later than the US and Europe, it needs more time to stop using fossil fuels like coal.

India, on the other hand, has not yet set a date for when its emissions will peak, though it has announced goals for increasing cleaner energy usage and reducing fossil-fuel consumption.

My Government firmly believes in the path of sustainable development. We are ensuring that development happens without harming the environment: PM @narendramodi

— PMO India (@PMOIndia) February 17, 2020

What do the EPI 2022 results signal?

Some results came as a surprise. Countries with more comprehensive climate policies, like Spain, are still not doing enough to reach these targets according to EPI 2022.

“This report’s going to be a wakeup call to a wide range of countries a number of whom might have imagined themselves to be already doing what they needed to do and not many of whom really are,”

– Samuel C. Esty, Director of the Yale Centre for Environmental Law and Policy.

The results also highlight that policymakers in many countries are not doing enough to meet climate targets. The US’ fall in rankings is a stark reminder of how a few years of inaction can throw a country off track and make it more difficult to progress again.

In sum, the EPI enables decision-makers to recognise what drives effective climate performance. The aggregate scores it provides for analysing performance help determine environmental progress and policy choices, and are valuable for both the public and policymakers.

The 2022 data shows how much a country’s financial resources, good governance, human development, and regulatory quality matter when it comes to sustainability efforts, so in highlighting these, the EPI promotes sustainable development in support of a more environmentally secure and equitable future.

However, some find issue with the EPI as a ranking system

Navroz K. Dubash, Climate expert at Centre for Policy Research New Delhi, believes that countries shouldn’t have to all progress at the same rate toward reduced emissions and net zero. As he said:

“This is neither ethically defensible nor a reflection of current political agreement[…] This is not to be an apologist for India – air pollution and local environment pollution are deeply concerning, and harm India’s poor the most. But it hurts rather than helps progress when indicators ignore legitimate, even essential considerations about justice in addressing climate change.”

The EPI researchers recognise that many countries face war and other sources of unrest as well as a lack of financial resources to invest in environmental infrastructure, but they do not include this in their rankings, which some argue could be considered a flaw.

Fittingly, at the recent World Economic Forum, the UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres claimed that a failure of climate action would be “the biggest threat to security that modern humans have ever faced,” but that an unjust climate transition would have terrible impacts, too.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Generating Station – Navajo, Arizona. Featured Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons.