Forests help stabilize the climate and provide many contributions to Sustainable Development Goals. And we have quite a bit of evidence about what policies and strategies are effective in conserving and restoring forests. So why haven’t such measures been adopted at scale? Our new working paper, “Public-Sector Measures to Conserve and Restore Forests,” commissioned by the Food and Land Use Coalition as part of its flagship “Growing Better” report, we identify six economic and political economy barriers, and identify strategies to overcome them.

But first, a quick review of why forests are important, and what we know about how to conserve and restore them.

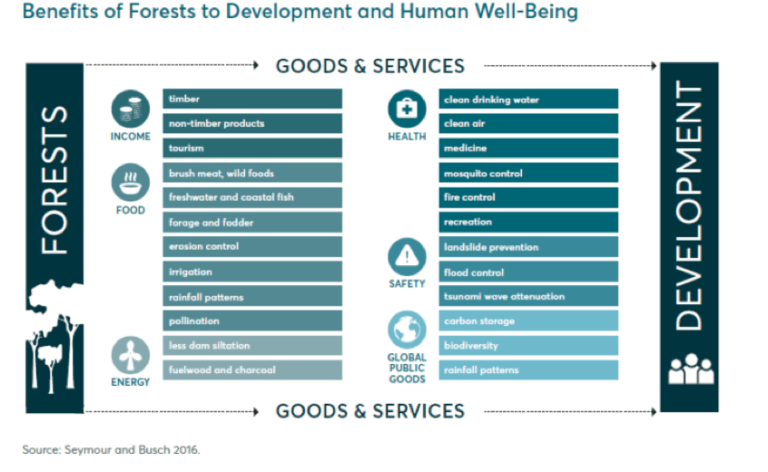

Forests provide a range of goods and services that generate income, food, energy, improved health, safety and global public goods.

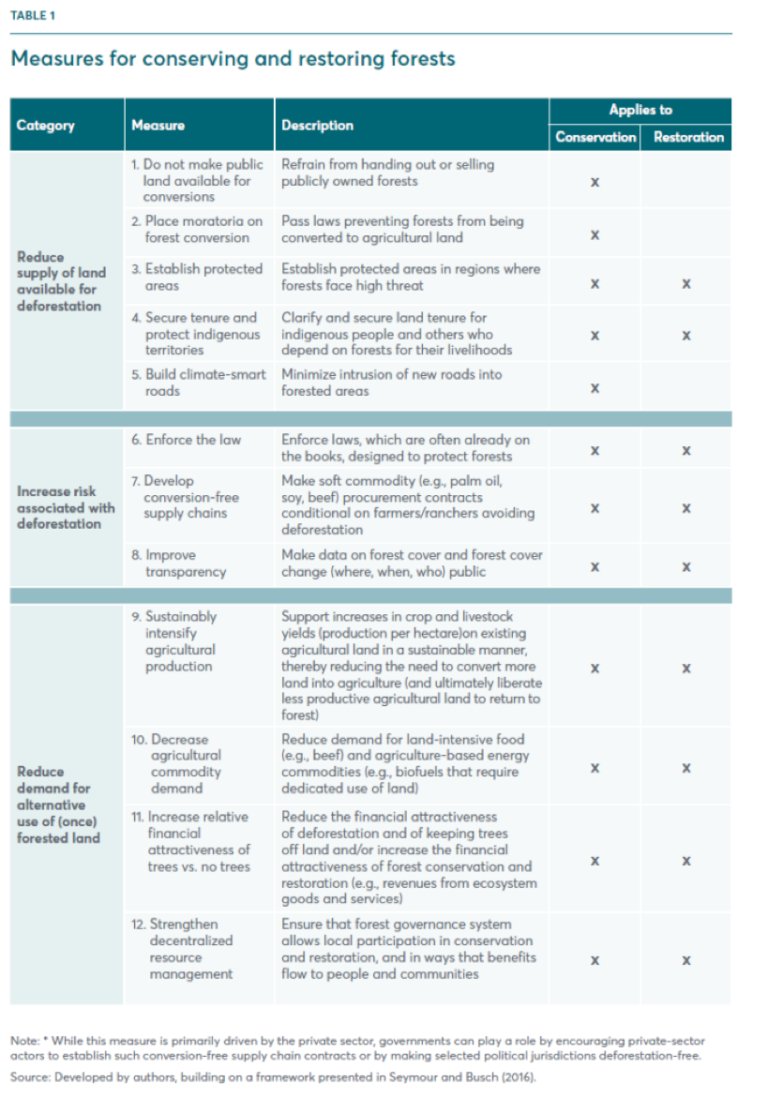

A number of public-sector measures have proved effective, or promise to be effective, at forest conservation and/or restoration (Table 1). The first category of measures reduces the amount of forested land available for deforestation. The second makes it expensive — politically, economically, legally, reputationally — to turn forests into agricultural land or other uses. The third reduces the economic pressure or incentive to convert forested land to farmland or to other uses and/or reduces the pressures that keep trees from recovering on land that was once forest.

The six barriers are:

1) Patronage and Power. Forests are often treated as a source of political patronage to be used to get and keep political power and support. An extreme example took place two decades ago, when then-Liberian President Charles Taylor routinely rewarded political loyalists with lucrative logging concessions.

2) Worth more dead than alive. Trees are often seen as obstacles to economic growth, while so-called development is seen as first extracting value from standing forests in the form of timber or biomass energy and then offering supposedly longer-term value of the land under the trees, either for grazing cattle, raising agricultural crops, extracting minerals or speculating on the value of a future sale.

3) Where’s the money? Financing forest conservation and restoration has proved difficult because many forest benefits are not monetized. And financial incentives supporting activities that drive deforestation or keep trees from coming back often outweigh the incentives for conservation and restoration.

4) Who’s the owner? Communities living in and around forest areas can play a vital role in successful conservation and restoration but are too often excluded from decision-making about forest policy in part because of unclear and contested land tenure. Indigenous peoples and local communities collectively occupy at least half the world’s forests but have legal rights to only about 10% of these lands (RRI 2015). The absence of secure legal rights leaves communities and their forests vulnerable.

5) Working at cross purposes. In some cases, governance over land that affects forests is not aligned, leading to policy paralysis, incoherence or even conflict. The governance of forests is often influenced by multiple agencies, operating at different levels, leading to fragmentation of interests, priorities and actions along horizontal (e.g., agriculture vs. environment ministries) and vertical (e.g., national vs. local government) lines.

6) Laws on the books but not in practice. Systemic corruption and low levels of law enforcement often exacerbate these barriers. Although progressive laws may be on the books to support forest conservation and restoration, there is little follow-through and illegalities continue to occur.

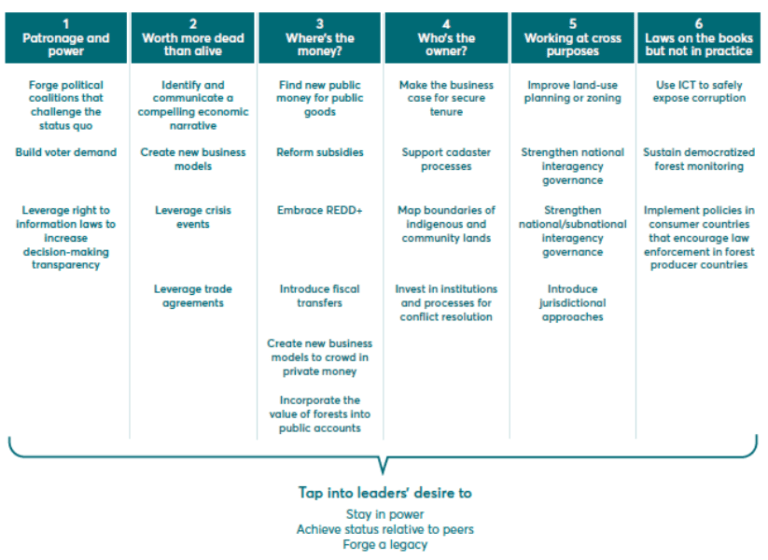

Figure 2. Strategies for overcoming economic and political economy barriers

We suggest a number of strategies to address each of these economic and political economy barriers (Figure 2). Overcoming patronage and power entails applying political pressure that dissuades public-sector leaders from handing away forests (or undermining efforts to conserving or restoring them) as a means of garnering and maintaining political power and support. Here are some examples of how to do this:

- Forge political coalitions that challenge the status quo, linking stakeholder groups such as civil society and business that might not have previously worked in concert.

- Build voter demand for improved forest management, including by raising awareness of the winners and losers from forest loss.

- Leverage right-to-information laws to increase decision-making transparency and expose malfeasance.

Overcoming forests being worth more dead than alive entails demonstrating to government and the private sector that conserved or restored forests result in more positive outcomes for political, business and human well-being than the status quo. Here are some examples of how to do this:

- Identify and communicate a compelling economic narrative, providing evidence of how protecting forests conserves current benefits and avoids long-term costs.

- Create new business models that generate revenue streams that depend on keeping forests standing. (For more on this, see Prosperous Forests).

- Leverage crisis events such as fires and floods attributed to forest loss to harness fleeting political will for action.

- Leverage trade agreements to build in incentives for legal, sustainable production of forest-risk commodities.

Related Articles: Climate Change in the Arctic | The Warmest Decade

Overcoming the “where’s the money” barrier requires making the case for finding sources of financing for which forest conservation and/or restoration earn a return sufficient to meet investor needs, whether that be a community, a business or a government. This has the potential to shift the decision calculus toward sustaining trees as opposed to clearing them or preventing them from returning. Here are some examples of how to do this:

- Find new public money for public goods.

- Reform subsidies by shifting incentives from activities that drive conversion of natural forests to other uses toward forest-friendly activities.

- Embrace REDD+ by establishing the markets and funds needed to incentivize performance at scale.

- Introduce fiscal transfers that reward subnational jurisdictions with a larger share of tax revenues in return for maintaining forests.

- Create new business models to bring in private money.

- Incorporate the value of forests into public accounts so forest products used for local livelihoods and forest-based environmental services are no longer given a value of zero.

Overcoming the “who’s the owner” barrier involves approaches that clarify and secure tenure of individual landowners, communities, and indigenous peoples. Here are some examples of this approach:

- Make the business case for secure tenure, noting the cost-effectiveness of local forest stewardship and conflict as a constraint on investment.

- Support cadaster processes that legally register parcels of land to individual owners to provide the spatial data necessary to enforce the law.

- Map boundaries of indigenous and community lands as a first step toward protecting indigenous people’s rights.

- Invest in institutions and processes for conflict resolution to build confidence that outcomes will be fair.

Overcoming the “working at cross purposes” barrier involves creating governance approaches or bodies that align management of forests across the myriad agencies that affect them. Here are some examples:

- Improve land-use planning or zoning to clarify areas that are “go” and “no-go” zones for forest exploitation or conversion.

- Strengthen national interagency governance to coordinate policies across sectors and ministries.

- Strengthen national or subnational interagency governance to align implementation across scales.

- Introduce jurisdictional approaches to support local government leadership and align contributions from civil society and private sector actors.

Overcoming the “laws on the books but not in practice” barrier entails implementing tactics recommended in the literature for reducing corruption, increasing transparency, and improving law enforcement more widely in society (not just as corruption and law enforcement relate to forests). Such tactics include ensuring an empowered independent judiciary, a free press, well-resourced law enforcement, and more. When it comes specifically to forest conservation and restoration, we highlight three tactics that may be particularly relevant:

- Use information and communication technology (ICT) to safely expose corruption.

- Sustain democratized forest monitoring to support effective law enforcement.

- Implement policies in consumer countries that encourage law enforcement in forest producer countries.

Finally, we can’t overlook what public sector decision-makers — including presidents, governors, and agency leaders — care about, namely staying in office by meeting constituent needs, achieving status relative to peers and forging a legacy. These motivators of human behavior are too often overlooked by those seeking to advance forest conservation and restoration, yet they are fundamental to what makes leaders tick. Efforts to overcome political economy obstacles to conserving and restoring forests should keep these motivators in mind and integrate appeals to these basic concerns into their strategies.

About the authors: Craig Hanson is the Vice President of Food, Forests, Water & the Ocean at World Resources Institute. Frances Seymour is a Distinguished Senior Fellow at WRI. Helen Ding is an Environmental Economist with the Economics Center at the World Resources Institute.