EDITOR’s Note: The original version of this article was published in UN Chronicle and may be found here.

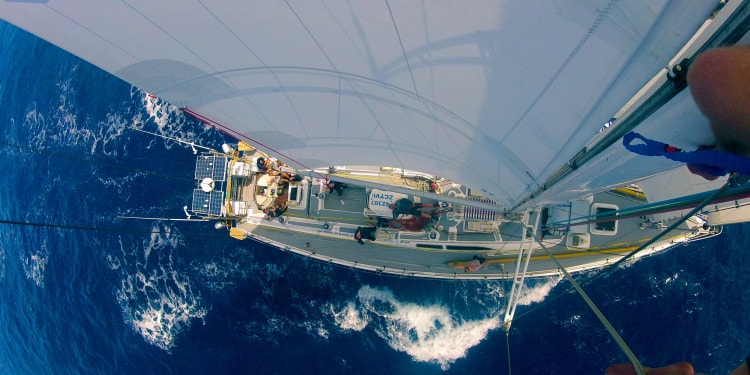

I was woken in the middle of the night by a thud on the hull of our boat. We rushed up on deck to find we were surrounded by pieces of plastic floating in the ocean. It didn’t make any sense. We were over 1000 miles from land. The closest people to us were in the space station, in orbit above our heads. And yet there was evidence of human life, and waste, all around us in one of the most remote parts of our planet.

I was just out of university and working my passage to Australia at the time, when this incident sparked a new career direction for me – sailing the world on a mission to connect people – scientists and communicators – with the ocean, exploring issues from the Equator to the Poles.

At sea I saw at first hand the collapse of fisheries, toxic chemicals accumulating in marine organisms, island communities relying on imported packaged food and the extent of plastic pollution.

We’d stop at small islands and find the locals could no longer catch fish to feed their families because commercial vessels had caused their fisheries to collapse. They could no longer grow crops in the ground as the rising sea levels had made their soil too salty. The consequence of this was a new reliance on imported food, that comes wrapped up and packaged in this strange new material – plastic.

In the Photo: Burning plastic in Tonga Photo Credit: Emily Penn

With no system in place to deal with this trash, it ends up being thrown on the beach, in the ocean and often burned. That stench of burning plastic kept getting up my nose, and when I started researching what that smell was, I learned about these chemicals – dioxins – that are formed during incomplete combustion of waste, and how they are carcinogens that can get absorbed into our bodies. This became my first mission: to eliminate the burning of plastic across a group of islands in Tonga.

The Tonga Challenge

As I started learning the Tongan language I realised there wasn’t a word for ‘rubbish bin’ on these South Pacific islands. The concept of throwing something away into a managed system didn’t exist in the culture, because it didn’t need to until very recently – organics could be thrown on the ground without problem. It wasn’t only infrastructure that was needed; it was a whole new way of thinking about this new inorganic material.

Six months of working and teaching with the local community culminated in a colossal cleanup and together with 3000 local volunteers we picked up 56 tonnes of trash, in just 5 hours. This amount of trash staggered me. Both what was being produced locally but also what was washing up on the shoreline each day, including items with packaging labels written in languages I didn’t recognise. This got me asking more questions – where was this plastic coming from and why was it ending up on these remote islands in the Pacific?

In the Photo: Plastic pieces. Photo Credit: Studio Swine

The Design Problem

It turns out we use nearly 2 million plastic bags, globally, every minute. Those bags are used once, maybe twice, probably three times at best. Then they are thrown away. Plastic is designed to last forever, and we then use it to make products like plastic bags and disposable bottles that are designed to be used once and then thrown away.

This mismatch of material science and product design puts us in this situation of having vast amounts of waste material that no longer has any use, or value.

Related Article: HEALTHY OCEANS: THE CORNERSTONE FOR A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE

But that’s ok, I thought. Can’t we just recycle all that plastic? Well no, apparently not. Less than 10 percent of plastic used in the United States ends up being recycled. A visit to a recycling centre showed me why that number was so low. Plastic is an umbrella term we give to many different materials that all have different properties – and therefore different chemical structures. To recycle them, first they need to be cleaned and separated, a lengthy and expensive process, which in itself consumes vast quantities of energy and water. There also needs to be a demand for people to pay more for recycled materials rather than opt for cheaper virgin plastic.

Given that we have all this used plastic with no place to go, it’s not surprising that we see tonnes – 8 million tonnes globally each year – washing down our streams and waterways into the ocean.

In the Photo: Kiritimati Island Dumping Site Photo Credit: Emily Penn

I learned about where plastic goes when it leaves the land. How it moves with the ocean currents and ends up accumulating in five hot spots – known as the five subtropical oceanic gyres. In the centre of the gyre (the large system of rotating currents) the ocean is calm and everything, whether it’s a piece of organic debris or a piece of plastic, is drawn to the centre. I heard about floating “islands” of plastic, but the more I learned the more I realised how little we collectively know.

And so this became the mission: to sail to these accumulation zones and find out what really existed there.

On a Mission to the Gyres

We went searching for islands of plastic – for areas that could be scooped up and brought back to land for recycling. But we quickly realised that the plastic was smaller than expected. It doesn’t just float around in big rafts on the surface. UV light photo-degrades it into tiny fragments. Some sink, and some are ingested by marine life. On my extensive voyages across the globe I discovered that it is the same story everywhere – not only in the gyres, but all the way from the Tropics to the Arctic. Our oceans have become a fine soup of plastic fragments.

Much of it can’t be seen from the surface by the human eye, which makes the seas look cleaner than they really are, and makes large-scale clean up an immense challenge. We had to take a fine net through the water to take a closer look. Each time we turned the net inside out, we would find hundreds of tiny fragments of plastic.

Photo Credit: Emily Penn

When we got the samples on board, we analysed them. I was shocked by how difficult it was to distinguish the plastic from the plankton. I wondered how fish would cope figuring out what is plastic, and what is their food. And so we caught fish and looked inside their stomachs, only to realise that there was plastic there too.

This opened up a whole new series of questions. Now, we were not only concerned about the effect plastic may have on the environment through its physical presence, but what about the chemical impact? Given that plastic is getting into the food chain – our food chain – could this mean toxic chemicals are getting inside us?

The Poison Inside

I decided to have my blood tested, to find out what toxic chemicals I have inside me. Working together with the United Nations Safe Planet Campaign, we chose to test for 35 chemicals that are all banned because they are known to be toxic to humans and the environment.

Of those 35 chemicals, we found 29 of them inside my body.

This is when things really changed for me. So often when we talk about environmental problems we hear about things that are happening somewhere else, to somebody else, at some point in the future. However, it seems you and I already have a body burden, a chemical footprint that we will never get rid of.

And while the concentrations of chemicals I currently have inside me are not alarmingly high, it’s a chilling indicator of the direction our society might be heading.

Photo Credit: Emily Penn

The Solutions

Exploration, understanding, and education are key to helping us figure out how to restore a healthy ocean. The issues are complex but the more time I spend at sea, the more I realise the solutions start on land.

There are ways to tackle the problem at every point – from source to ocean – from product design to waste management. But to solve these problems long term we need to turn off the tap. We need to work at the source. This upstream action is required across all sectors of society; working with designers in industry, policymakers at a government level and all of us as individual consumers.

If we want to continue to count on the ocean as a source of food, energy, transport, and minerals for generations to come, we need to stem the flow of waste, and devise more sustainable ways of using this vital resource. As I learned on my journey, we care most about things we feel connected to. We urgently need more awareness of our blue planet to regain that connection and inspire action.