The recent #MeToo campaign on social media was revived by actor Alyssa Milano as a response to the sexual harassment allegations against media mogul Harvey Weinstein. She wrote on her social media timeline in mid-October: “If all the women who have been sexually harassed or assaulted wrote ‘Me too’ as a status, we might give people a sense of the magnitude of the problem.” The hashtag originated more than 10 years ago with activist Tarana Burke. Since Milano’s tweet, millions of people have shared their stories, and, unlike other times outpouring of stories has occurred, this time many men in powerful positions have had to publicly acknowledge their deeds and/or resign from their positions.

If you’ve been sexually harassed or assaulted write ‘me too’ as a reply to this tweet. pic.twitter.com/k2oeCiUf9n

— Alyssa Milano (@Alyssa_Milano) 15 октября 2017 г.

On my social media timeline, there have been several discussions on why has it taken this long for women to share their stories and how could this happen to ‘successful’ and ‘literate’ women. Mind you, it appears to be shocking to many that most of these stories coming to light are from the Western World or the Global North.

But to me it is not surprising at all.

For the past five years, I have dedicated my life to working on the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. The very fact that it finds a place amongst the 17 SDGs should indicate how serious of a problem it is and how important it is for everyone to step-up and correct the situation by 2030.

IN THE PHOTO: Wall art. PHOTO CREDIT: Safecity

According to UN Women, on average one in three women around the world experiences some form of sexual assault at least once in their lifetime. No country in the world is untouched by the pandemic of intimate partner violence—1 in 5 women and girls aged 15 to 49 across 87 countries reported experiencing physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner; 49 countries have no laws specifically protecting women from domestic violence. Harmful practices, such as child marriage and female genital mutilation (FGM), continue to rob women and girls of equal opportunities. The numbers are staggering— at least 200 million women and girls have undergone FGM, and over 750 million women and girls alive today were married before their 18th birthday.

Related article: WHY SHOULD FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION MATTER TO ALL OF US? by Ana Perianes

The UN informs that the targets to achieve SDG 5 include putting an end to all forms of discrimination and violence against women and girls everywhere, both in public and private spheres. It further aims at eliminating harmful practices, such as child, early and forced marriage, FGM, trafficking and other forms of exploitation. It seeks to recognize and value unpaid care and domestic work through the provision of public services, infrastructure and social protection policies and the promotion of shared responsibility within the household and the family as nationally appropriate. Finally, it strives to promote women’s full and effective participation at all levels of decision-making in political, economic and public life, provide universal access to sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights as agreed in accordance with the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development and the Beijing Platform for Action.

These targets are all interlinked. You cannot isolate one from the other and whilst I have chosen to work on making public spaces safer for women and girls, my efforts do highlight and touch upon every single one of these targets.

IN THE PHOTO: Elsa Maria D’Silva. PHOTO CREDIT: Safecity

I started Safecity, a crowd map for sexual violence in public spaces, in response to a horrific gang rape of Ms. Jyoti Singh on a bus in Delhi in December 2012. Through the platform, people can share their stories, anonymously if they wish, and these are collated as location-based trends, visualised on a map as hotspots. The aim is to make this information available in the public domain so that neighbourhoods can be made safer through individual awareness, collective community engagement and institutional accountability.

Through my work at Safecity, I found that many people do not fully understand the entire spectrum of sexual harassment and abuse. Often, they think of it as only the most extreme form which is sexual assault or rape. But on a daily basis, they tend to ignore the verbal, non-verbal and other physical forms of it.

Sexual harassment ranges from staring, leering and ogling, to commenting, catcalling, sexual invites to physical touching, groping, masturbation in public spaces, use of technology where pictures and videos are taken without ones’ permission and trolling.

Stalking is not only physical but also a virtual form of harassment. This is extremely harmful though we may think of it as ‘trivial’ when in fact they could be limiting our choices, our opportunities, restricting our mobility and movement and affecting our mental health.

This apathy or ignorance about the range of abuse creates a situation of insecure cultures where we ‘normalise’ and accept this kind of sexual harassment putting the onus on the person experiencing it to protect herself/himself whilst bystanders don’t intervene, and authorities turn a blind eye because there is not enough data to support it. Many people do not report it due to fear of bringing shame to themselves and their families, fear of the police’s insensitivity and the lengthy judicial process for justice. Hence the official statistics do not reflect the true nature and size of the problem.

That’s where Safecity is able to bridge the data gap and provide a platform to not only record and document people’s experiences but also make a new dataset available for decision making – at the individual, community and institutional level.

Today we use technology to help us make various choices in different aspects of our daily life, be it Trip Advisor when picking a hotel, Yelp for a restaurant, Good Reads for a book. Yet, when it comes to sexual violence we hardly talk about it, while in fact, we can use technology to improve our situational awareness to make better choices for our safety. For example, you can decide which metro station you would feel more comfortable alighting at, what kind of public transport is best suited to your needs and, more importantly, you will have local information that will allow you to be better prepared to respond to any situation quickly.

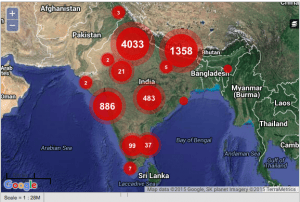

IN THE PHOTO: Map indicating the level of safety in different cities in India. PHOTO CREDIT: Safecity

At one of our workshops in a local girls’ college in Mumbai, we did a mapping exercise. Seeing the hotspots on the map and hearing each story allowed the girls to see they were not alone in their experiences. They suddenly realised that the harassment they were facing was not brought upon themselves because of the clothes they were wearing or the time they were in that place. In fact, one of the girls even said out loud in surprise: “Oh, I had no idea that it was happening to everyone and not just me!”. Visualising this data on a map thus helps us shift our perspective and question what it is about the location that makes it the ‘comfort zone’ of a perpetrator. Also, when people realize it is not their fault that they have faced sexual harassment, they are more likely to want to take action.

Then we come to the next bit, the community. We are all part of communities, yet we turn a blind eye to the many incidents that are happening around us. We don’t want to ‘interfere’ or get involved. Yet, we can all prevent sexual harassment from happening – say something, ring the bell in the case of domestic violence like Breakthrough has advocated: call the police, show solidarity with the person being abused, talk to male friends and colleagues and challenge toxic masculinity.

Parents have a huge role in bringing up their children with equality, without favouring or promoting one gender over the other and being great role models where the household work is shared, and roles are fluid rather than stereotypical.

We have a great example, where our map helped us identify a hotspot in an urban slum in Delhi. It was on a main road near a tea stall. Men would loiter there while drinking their tea and intimidate women and girls with their constant staring. When asked what they wanted to change about their neighbourhood, the young girls said that they would like the staring to stop. So we organised an art workshop for them and they painted the wall with staring eyes and subtle messaging that loosely translates in English: “Look with your hearts and not with your eyes”, “we won’t be intimidated by your gaze”, “we will not hide”, etc. It’s been over two years since the wall mural was painted and the staring and loitering have stopped. The girls can now walk comfortably, with no stress, to school, college or work, without fear of being intimidated by those men.

IN THE PHOTO: Street art. PHOTO CREDIT: Safecity

In another example, in Kibera, Nairobi, a hotspot where young men were groping girls on their way to school, was near a mosque. My partner organisation invited the Imam for a discussion, showed him the data and he went back and incorporated the messaging into his sermons. It had a positive impact amongst the young men and the abuse reduced.

In many low-income communities, young girls drop out of school because it is not safe for them. Under the guise of safety, their parents make them stay at home to ‘protect’ them till they are ready for marriage which is again in most cases 15 or 16 years of age. Making public spaces safer is critical for a girl to get an education and then a career leading to financial independence.

Changing cultures of violence is partly about policies, but it’s also about giving people a voice. By making it easy for people to share their stories and report, and thus transparently showcasing data, we can hold institutions accountable.

We use the online data that women and girls share to identify factors that lead to behaviour that causes sexual violence and help us think through strategies to find solutions. We have successfully used the information to engage over 400,000 citizens, police, municipal and transportation authorities in India and abroad. We have several examples where the data has caused police to change beat patrol timings and increase patrolling and municipal authorities have fixed street lighting and made safe public toilets available. Together with a partner organisation in Nepal, we pressured the transportation authorities to issue ‘women only’ bus licences.

There is a drive to increase the number of women in the workforce. But once again, is it a level playing field if public spaces and workspaces are not safe for women? It is important to create an environment where a woman does not always have to worry about her safety but can concentrate on giving her best self at work and at home.

Last week I spoke at the Women of the Future Summit in London and asked a room of over 350 delegates to raise their hand if they have never been harassed in their life. Not a single hand went up. I believe the time has come to take firm measures on achieving SDG 5 and true gender equality where every woman and girl has the right to live her life without fear, with dignity and respect in an environment that is truly equal.