Audrey Azoulay, director-general of the United Nations Educations, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) appointed Lazare Eloundou Assomo, from Cameroon, as head of the World Heritage Centre on December 6, 2021. This marks the first time in history that an African national will direct the World Heritage Centre.

Mr. Assomo, a graduate in architecture (Grenoble School of Architecture, France) and in urban planning (DEA Grenoble 1), has a long experience with both the World Heritage Centre – from 2008 to 2013, he was Head of the Africa Unit and coordinated several major restoration projects – and Unesco which he rejoined and served in the field, heading the Bamako and Mali offices, returning to headquarters in Paris in 2016, initially as Deputy Director of the Heritage Division and of the World Heritage Centre, becoming in 2018 Director of Culture and Emergencies.

In that role he coordinated emergency conservation responses to heritage affected by conflicts and disasters and the restitution of cultural property under the 1970 Convention, the international treaty to combat illegal trade in cultural items. He notably led the reconstruction of the Timbuktu mausoleums after they were badly damaged in 2012 by Islamist fighters allied to al-Qaida. He has since voiced his wishes to address the global north and south divide when it comes to the appointments of World Heritage Sites.

He hopes to address the power and financial imbalances within the World Heritage Centre that greatly benefits rich nations and hopes to protect sites threatened by the climate crisis and war.

Africa and its forgotten treasures

Although the African continent has a land area of 30.37 million square kilometre – enough to fit in the U.S., China, India, Japan, Mexico, and many European nations, combined – it has never been proportionately represented on UNESCO’s world heritage list.

Whilst it is true that the size of a continent should not be the sole determinant when considering the expected total number of World Heritage Sites, here, the facts and figures provide a pretty bleak picture of the power and financial imbalances within the organisation.

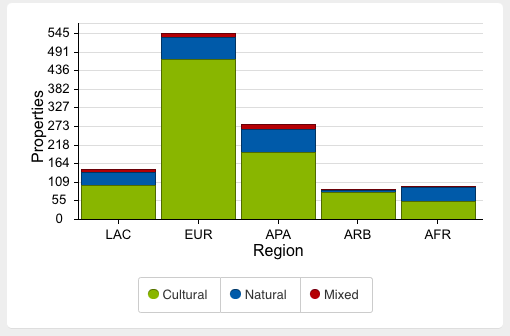

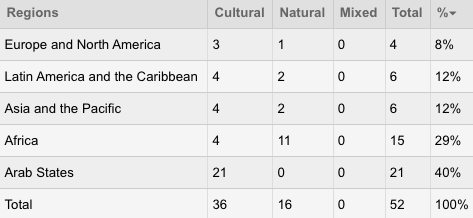

Africa’s total count of 98 (8.49%) cultural and natural sites is completely dwarfed by Europe and North America’s total of 545 (47.23%). At the top of the podium for the total number of sites included in the World Heritage List, we have Italy (58), China (56), and Germany (51). Those at the other end of the spectrum, are mostly small island developing states. Out of the 27 countries with no sites of any kind on the UNESCO list, only four are not either in Africa or classed as a small island state.

Wealthy countries, thus, make the most of the tangible influx of money and tourism that comes from the more abstract notion of recognising a country’s heritage.

Too often has many aspects of the continent’s rich cultural heritage and natural sites been ignored in the application of the World Heritage Convention and in the discussions during conferences. Yet, the presence of these individual national treasures on the African continent are not lacking.

Overcoming the disparity in available funding and resources for developing countries

Assomo has set himself the goal of redressing the imbalances that greatly benefit richer nations by tackling the greatest obstacles to the complex and costly nomination process for a site to be included in UNESCO’s Heritage list: resources and expertise.

The World Heritage Fund provides on average $4 million to UNESCO to assist with the activities that concern cultural heritage sites. This is a modest sum in comparison to UNESCO’s total annual budget of $518 million for 2020-2021. The budget that UNESCO receives for these activities are simply not high enough to redress the imbalance between states in terms of heritage.

The whole organisation is under-funded with the US still owing $543 million in arrears, having paid nothing since 2011 in retaliation for Palestine’s membership in the organisation.

Even if greater funding was available, nations need expertise to prepare for nominations. “The training and capacity-building of heritage experts is an area where we will have to put more emphasis [on] the future to help address this imbalance,” Assomo told The Guardian.

Assomo would like to see greater cooperation between member states, with countries in Europe helping to fund training programmes in developing countries and small island states. Also he hopes wealthy nations could provide greater funding for the World Heritage Fund and the African Heritage Fund to ensure money is no longer an obstacle to saving cultural heritage sites.

The need to challenge our Eurocentric universalist views on cultural heritage

The Convention (mentioned above) concerning the protection of the world’s cultural and natural heritage came into force when sufficient UNESCO member nations signed it in 1972. It links together in a single document the concepts of nature conservation and the preservation of cultural properties. It recognises the way in which people interact with nature, and the fundamental need to preserve the balance between the two.

Related Articles: World’s Oldest Tropical Rainforest Handed Back To Original Indigenous Custodians | The World’s Largest Mangrove Forest Is Shrinking | The Effects of Globalisation on Languages and Cultural Diversity

Although the concept of cultural heritage and the meaning of several terms written in 1972 have since evolved to encapsulate more than simply architectural monuments, one reason for the imbalance in UNESCO World Heritage sites today still pertains to UNESCO’s historical Eurocentric view of what “cultural heritage” was and should be.

For example, the “sacred forests” of West Africa, are patches of land that have been preserved for a long period of time because of their cultural or religious significance. These “sacred forests” are believed to be inhabited and protected by gods, totem animals or ancestors. These forests are considered the last remnants of ecological niches and thus, must be preserved.

The long journey towards listing the Sacred Mijikenda kaya forests in Kenya’s coastal strip as UNESCO World Heritage Sites is another example of the difficulties caused by the universal views of cultural heritage still encapsulated in the 1972 Convention. In recognition of their rich natural and cultural heritage, and because of the kayas’ unique nature as high biodiversity, traditionally conserved sites, the Kenya State Party decided to present them for listing between 1992-1999. Kenya had to wait until 2008, for eleven Mijikenda kaya to be grouped and added as a World Heritage Site.

Climate change, environmental degradation and conflict are threatening cultural heritage sites

This said, climate change remains the biggest threat to natural world heritage, with a third (33%) of natural world Heritage sites concerned, according to a report published by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

15 African sites make up nearly 30% of the “in-danger” world heritage list, due to a variety of threats including poaching, illegal logging, and conflict.

Close to Assomo’s heart is the impact climate change has on Timbuktu’s mausoleums, greatly affected by the long-term desertification, but other sites are also a matter of great concern. For example, the Cape Floral Region Protected Areas of South Africa has been affected by the growing spread of invasive species.

This is why Assomo calls for the greater protection of sites currently affected by climate change, environmental degradation, and conflict, as well as for the implementation of greater preventive measures for sites that may be impacted in the future.

Assomo provides a gleam of hope in redressing the power, financial, and training imbalances that have insofar worked to the advantage of wealthier nations – and also helped to feed a certain amount of indifference or blindness to the value of extra-European cultures – which has come at the expense of recognising significant cultural heritage sites in developing nations.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Boy in front of Timbuktu mausoleums, Mali. Featured Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons.