Imagine you lived in a house with 100 people. Or, to be more precise, with 25 children, 66 mid-aged adults, 9 senior citizens …

31 are Christians, 23 Muslim, 46 practice another religion or don’t follow any. 12 people in your house speak Chinese as a first language, 6 speak Spanish, 5 English, 4 Hindi, 3 Arabic, Bengali, or Portuguese, 2 speak Russian or Japanese. 60 speak other first languages. 86 can write, 14 can’t. 78 people actually live in your house. Some in spacious rooms, some in small ones.

Most rooms are shared by several people. 22 people sleep outside the house, in rain, storm or snow. 12 people in the house are undernourished. You pass by them every day. One of them is actually dying of starvation. 22 are overweight. 9 people in your house cannot access clean, safe water to drink. 18 people only have access to basic toilets. 14 people have no access to toilets at all.

One person owns as much wealth as the other 99 combined.

Your house is near the water and the water levels are rising. Some rooms are going to be flooded soon. The lowest rooms already have water in them. Some people will be able to leave their rooms and move to others, some people won’t be able to leave, when the water makes their rooms uninhabitable. The house looks like it has no roof, but there is an invisible dome around the house, which cannot be opened. The air in the house can only be cleaned from what is inside it. Some rooms have plants that create oxygen, but some people cut them down to plant food for cows, pigs and chickens in your house, which some people eat. Cars – fuelled by petrol and diesel – drive through your corridors. The doctor in your house can treat some people for free, those who have insurance, while others don’t get medical support at all.

82 people in the house have electricity, while 18 don’t. With one fridge some of them use up more electricity than others do with all of their electronic devices combined. Energy is created inside the house. There is a coal mine, a power plant and an oil field. Some people in your house are immediately affected by war: They shoot each other, use gas,bombs and torture, others are forced to flee. Some knock on every door in the house to find shelter from the threats. During the next two years two people are going to take their own lives; three will die from road traffic injuries.

47 people in your house would not say they are happy.

This is a powerful metaphor for our world. Many more facts could be added to shape the image of a globe that suffers from violence, destruction and injustice. I could add numbers for sexual assault, human trafficking, discrimination and much more. It would be frustrating. And I can trust in your own knowledge of the world that you can extend the image to other problems and picture their effects on your everyday life, if they happened in your immediate surroundings, your home that you share with others.

In a scenario like the one above, what would we teach our children? And how would we teach them, if we saw the world as it is: A place we share as human beings, where our lives and our actions are connected? How would this education that keeps the world in mind differ from the education we currently provide?

Currently the education in our house looks like this:

Out of the 25 kids, 19 have a teacher, while 6 have no access to primary education; 8 have no access to secondary education. Not all kids have access to free education.

Gender disparities prevent equal access to all levels of education. It is more difficult for children with disabilities, indigenous backgrounds or in vulnerable situations (like war, zones or natural disasters) to go to school. Whether the teacher is qualified or not cannot be said.

Education mostly focuses on the development of cognitive skills. We teach our students knowledge. Even if we stress emotional development and approaches that focus on action, we still mostly test cognitive abilities and knowledge, not impact, and therefore prioritise knowledge in our lessons.

What would you teach the kids in this house, if you were their teacher?

Would you teach Latin, Literature and Logarithms first? Would you teach our children ANYTHING without showing them how it can be used to create peace and health in our house? Or to allow for them to figure out how they can make a difference and what they need to learn to effectively support the healing processes in the community? Would you even sit down with them and open a book, while there is still starvation, vendetta, violence and war in the corridors of the house you live in?

In a scenario like the one above, it would be obvious for us to allow for our kids to wonder: How can I use what I just learned to make our lives happier, healthier and more humane? What do I need to learn to help? And then let them be agents of change. And let them experience self-efficacy, let them develop their problem-solving skills, feel their impact. We would never again teach anything that doesn’t offer an opportunity to contribute to peace in our house.

“Education is not preparation for life; education is life itself.“ (John Dewey)

The role of education for a peaceful world has been stressed by many philosophers and educators. Aristotle already explained that “Education of the mind without education of the heart is no education at all“, and he surely inspired Malala who says: “I truly believe the only way we create global peace is through not only educating our minds, but our hearts and our souls.“ According to the definition of Harris and Synott, Education for Peace draws from people their desire for peace, nonviolent alternatives for managing conflict, and skills for critical analysis of structural arrangements that produce and legitimise injustice and inequality.

Maria Montessori stresses the role of pedagogy for world peace, when she says that “establishing lasting peace is the work of education; all politics can do is keep us out of war.“ Kofi Annan agrees: “Education is, quite simply, peace-building by another name, it is the most effective form of defense spending there is.“

Gandhi also attributes an important role to education: “If we want to reach real peace in this world, we should start educating children.“ And Mandela: “Education is the most powerful weapon we can use to change the world.“

But do our current school cultures reflect these pedagogical guidelines? Do we let our students create change?

You might argue, that the “real“ world consists of a few more than 100 people. You might argue that the 25 children and their teacher in our house that is the world, cannot achieve a lot. But is that true? Until I realised how big the impact is that teachers can have on each other, I thought I was just one teacher in one school, teaching a few classes per week, having a small impact on 150 students and their reading/writing skills. It wasn’t until I taught a unit called “Making a Difference“ that I realised that we, teachers, are crucial. I asked all the 15-year-olds I taught who they thought could make a difference in the world. And all of them said: “Nobody can make a difference. Certainly not I.”

John Hattie, one of the most influential education researchers of our day and age, found out that the most important factor with regards to successful learning is the teachers’ awareness of the impact they have. I realised that my students are not the only students in the world. There are 1.2 Billion students in primary and secondary education right now. And almost 2 Billion young people, under the age of 15: More than 25 percent of the world population. Each of our students spends 7,000 hours with teachers before they leave school. If we know our impact, we can use this time to raise the first generation “that can end extreme poverty, the last that can end climate change“, as Ban Ki-moon said.

Teachers I met from all over the world showed me beautiful examples of what their students can do: Researching and reducing over-fishing in Morocco, establishing the first composting plant in Paraguay, growing and harvesting fruit and vegetables in roof gardens in the South Bronx, presenting speeches for animal rights, designing incubators for students in other parts of the world, where water is dirty and food is scarce, educating their community about HIV, advocating against Female Genital Mutilation; I could name hundreds of examples. All of these kids have learned: they do make a difference!

Poverty and climate change are not the only issues on the list. The curriculum should be guided by nothing less than the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), 17 Global Goals for a healthy planet, guiding kids towards becoming conscious citizens of the world.

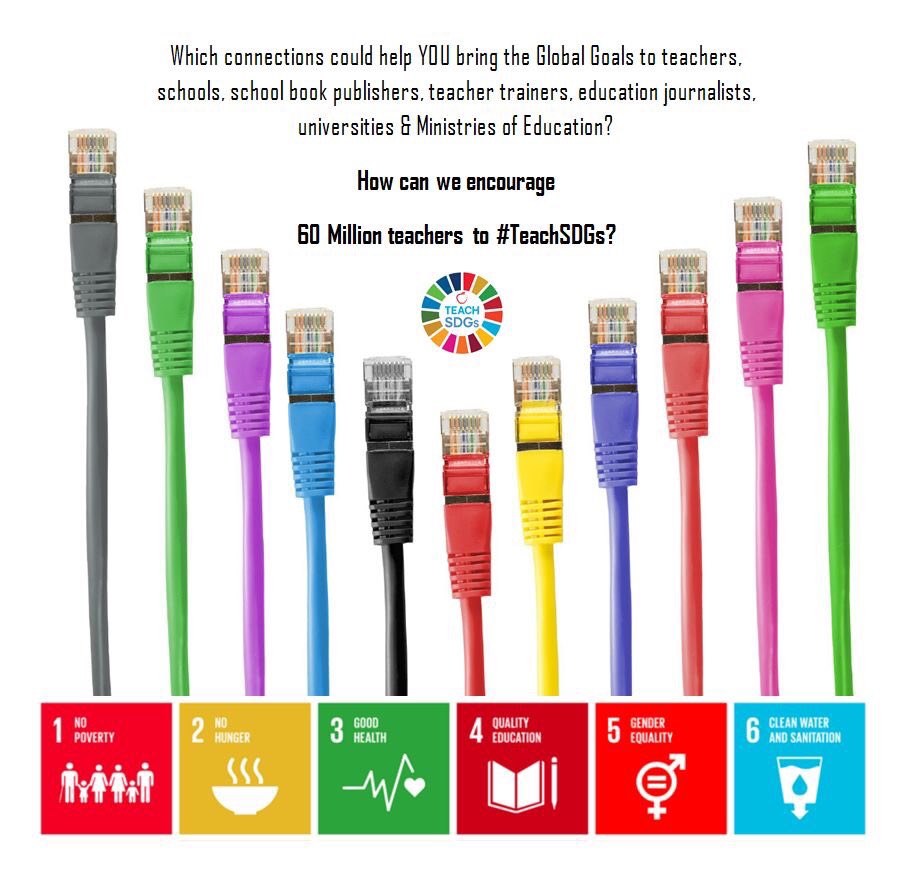

According to SDG 4, Quality Education doesn’t only refer to free and equitable education for all, but to an education that ensures “that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development […], human rights, gender equality and a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development.“ This type of education is supported and constantly developed by a number of stakeholders in the education sector such as UNESCO, the World’s Largest Lesson, the Council of Europe’s Pestalozzi Programme and the Global Educator Task Force (@TeachSDGs): a connection of thousands of educators and education ambassadors who encourage students to make a difference by increasing their ability to learn, feel and act on behalf of the planet.

According to SDG 4, Quality Education doesn’t only refer to free and equitable education for all, but to an education that ensures “that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development […], human rights, gender equality and a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development.“ This type of education is supported and constantly developed by a number of stakeholders in the education sector such as UNESCO, the World’s Largest Lesson, the Council of Europe’s Pestalozzi Programme and the Global Educator Task Force (@TeachSDGs): a connection of thousands of educators and education ambassadors who encourage students to make a difference by increasing their ability to learn, feel and act on behalf of the planet.

So, how would we teach in a house of 100?

1. TELL EVERYONE

First, we would make sure that everyone in the house knows that there is a plan for a healthier life for all of us, with less injustice, more peace, better and fairer conditions. We would want everyone to know about the plan and therefore we’d spread the word to all kids and grown-ups. At school we’d put up posters of the Sustainable Development Goals. We’d inform our students, parents and fellow teachers, discuss the Goals and decide whether and how we should help work towards them.

- FOCUS ON SDG-RELATED TOPICS

Secondly, we’d focus on SDG-related topics. We’d research poverty, climate change and peace. We would craft potential solutions and helpful programmes. In our current schools, we should do the same: Explore the background of these topics and show how they are connected to the SDGs. We can find suitable material and inspiration from The World’s Largest Lesson, the course Teaching Sustainable Development Goals from Microsoft Education and many other sources. In all countries we’d let school book publishing houses know there is a need for more SDG-related material.

- ENCOURAGE PROBLEM-SOLVING AND MEANINGFUL ACTION

Thirdly, we’d add a new focus to teaching units: ACTION. What can be done? How can we do it? How can we improve our shared home? Every teaching unit would include an element of action. Be it a letter that they write or a food programme they develop. Be it building water filters or making education videos for their own families or for others. Your newly empowered students will see with their own eyes how they can make a difference.

- DEDICATE A DAY OR WEEK to the SDGs.

If we notice that we still need to involve more people in the house, we’d prepare a day or a week to raise more awareness and encourage everyone to brainstorm how they could contribute. In our schools we could have the SDGs as a theme for the school fair. Or we’d be planning a week of project-based learning. The Global Goals are an inspiring theme and you can get your whole school and the surrounding community on board. What is the mayor’s plan with regards to the Global Goals? Your school fair might inspire politics and parents.

- MAKE CONNECTIONS

In your school in the house of 100 you’d quickly start connecting subjects. It would just make sense to research the chemistry and construction of water filters, develop an action plan, write a proposal for funding, create a convincing video and have elements of all subjects support the project. You’d have your students connect with experts for advice.And let them reach out to students in other areas of the house, those that are outdoors, those that don’t have access to education, or those who are in areas that suffer from undernourishment. In the 21st century, videoconferencing is a cheap, safe and time-efficient way to connect with the world. Your students will love to be connected and will understand how collaboration works.

- ENCOURAGE STUDENT LEADERSHIP

Soon, you’d be working on several projects. As a teacher, you cannot be in charge of all of them. Your students will be eager to learn and make a difference. You let our students be in charge. You’d help them find the support they need, help them find their strengths.Your students will be the experts – you will be their assistant.

- CREATE A CULTURE OF APPRECIATION AND GROWTH

Everything your students do towards achieving the Global Goals is going to be worth encouraging feedback. You’d have an amazing job, going from student to student, impressed by their achievements and ideas. You’d be motivated to help them reach the next level to make their actions even more impactful. We’d finally create a real culture of appreciation in our schools and in society. Teachers and students will be part of the same team. We live in a house of 100. Only it is a little bit bigger.

We live in a house of 100. Only it is a little bit bigger.

You can try to close doors and borders and pretend that we don’t live together on this planet, but we do. We breathe the same air, we drink the same water – we feel sadness over the same injustices in the world. We cannot pretend we’re not connected.

If we changed our education to cognition, emotion and action for a better planet, we would focus on a very specific Global Goal: SDG 4.7, which states that our education systems should develop global citizens in service to all 17 Global Goals. The indicator to monitor SDG 4.7 is defined as the “Extent to which (i) global citizenship education and (ii) education for sustainable development, including gender equality and human rights, are mainstreamed at all levels in: (a) national education policies, (b) curricula, (c) teacher education and (d) student assessment.

Unfortunately, many teachers from all countries of the world report to us that they hadn’t heard about the SDGs until they started working with international organisations. They also note that student assessment in most places does not yet include enough elements of action and impact. We notice that once teachers are aware of the Sustainable Development Goals, they are keen to teach their students and they want to learn about methods of teaching the SDGs. Many report that there are no opportunities organised by their national Ministries of Education. While all countries have agreed to implementing the SDGs, few of them have linked their national curricula and their teacher training with Global Citizenship Education.

In ancient Greece, Diogenes declared himself a citizen of the world.

Global Citizenship Education means that we teach all learners to know, feel and act on behalf of the planet, to contribute to a peaceful life in our house of 100, or the world of 7.5 Billion.

We are all threatened by climate change and war. We all need food, health, reduced inequalities and peace. Still, not all educators know how to create a connection or initiate a collaboration. Not all educators know how to set goals with students, work on a project and encourage student leadership. Not all educators and students know: they can make a difference. The SDGs help us focus on human similarities instead of human differences, on solutions that unite us, instead of problems that separate us.

Therefore, it is crucial that we all advocate for implementation and funding of activities that help teachers #TeachSDGs:

- Create opportunities for educators to promote the concept of Global Citizenship Education.

- Train teacher trainers on how to help teachers become globally-minded educators who initiate world-wide collaboration.

- Adapt national curricula to focus on Global Citizenship Education.

- Provide funding for research on the development of Global Citizenship Education.

“To find out what one is fitted to do and to secure an opportunity to do it is the key to happiness“ (John Dewey)