Democracy doesn’t work. Plato thought it was a terrible system, a prelude to tyranny, giving power to selfish and dangerous demagogues. Watching what is happening these days in democracies around the world, it’s hard to disagree with Plato. Democracy appears to produce an abundance of incompetent and dishonest political leaders, who exploit people’s credulity and prejudices and thrive on emotion-driven discourse and fake news. This Impakter essay looks at the problems and proposes an easy fix – if only we had the courage to implement it.

First, let’s quickly review what’s wrong with democracy.

Why People Have Lost Trust in Democratically-Elected Politicians: The Rise of Incompetent Political Leaders

Most people don’t trust democracy to deliver. According to 2019 Pew survey, trust in government is at a historical low: only 17% of Americans today say they can trust the government to do what is right “just about always” (3%) or “most of the time” (14%).

The situation in the rest of the world is not much better. A 27 countries Pew survey (April 2019) revealed that a majority (51%) are dissatisfied with the way democracy is working. Anti-establishment leaders, parties and movements have emerged on both the right and left of the political spectrum. And most people in developing countries find authoritarian figures more trustworthy than democratically-elected politicians. Hence the success of the “China model”.

Bottom line, elections don’t deliver the kind of political leaders people want.

After a honeymoon period between voters and their winning candidate, often as short as a month, he or she always disappoints. Why? Is it the fault of the voters, do they expect too much? Or don’t they understand what is going on – how complex the job of governing can be, how campaign promises can’t be kept?

It has been convincingly argued that, yes, it’s the voters’ fault. Dambisa Moyo, the well-known Zambian economist and author of Dead Aid (2009) in which she famously argued that foreign aid made Africa poorer, placed the blame squarely on voters:

“Voters generally favor policies that enhance their own well-being with little consideration for that of future generations or for long-term outcomes. Politicians are rewarded for pandering to voters’ immediate demands and desires…”

This quote is out of an article she wrote for Foreign Policy when her new book came out in 2018, Edge of Chaos Why Democracy Is Failing to Deliver Economic Growth — and How to Fix It. The article sums up her book’s arguments. In a nutshell:

“Because democratic systems encourage such short-termism, it will be difficult to solve many of the seemingly intractable structural problems slowing global growth without an overhaul of democracy.”

Let’s put aside for the moment the question whether our overall goal should be “global growth”: A good argument could be made that the unrestrained pursuit of continued economic growth in a world of finite resources (and where there is no Planet B) can only be achieved at the expense of the planet’s ecological balance.

Yes, climate change is real, have you heard? Ms. Moyo appears not to consider the possibility. But she does make some excellent points regarding “governance” – how we humans govern ourselves. And in particular, governance in a liberal democracy which is (still) considered, to use Churchill’s phrase, the least bad system. The actual quote is: “Indeed it has been said that democracy is the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time…’ Obviously, democracy is always better than dictatorship.

So what are the obstacles to good governance? Let’s list the obstacles Moyo has identified – plus a few of my own:

(1) Too many elections: She sees “the short electoral cycle embedded in many democratic systems” as a major problem: “Frequent elections taint policymaking, as politicians, driven by the rational desire to win elections, opt for quick fixes that have a tendency to undermine long-term growth.” This “public and private myopia”, she contends, is behind the collapse of American infrastructure; she cites the 2017 report by the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) that found 2,170 high-hazard dams, 56,007 structurally deficient bridges (9.1 percent of the nation’s total), and estimated that $1 trillion was needed to upgrade drinking water systems over the next 25 years.

The same can be said of European infrastructure: the collapse of bridges in Italy, notably the Morandi bridge in Genoa is a case in point; Germany with its aging highways and insufficient airports is in no better shape;

(2) Interest group lobbying: This is something Moyo highlights: Politicians respond to the demands of their funders instead of their voters; this can destroy democracy, resulting in the One Percent governing the 99 Percent; or, as Moyo puts it: “It is the use of wealth to influence political outcomes that helps inequality take root. Until democracies push back on the use of wealth to influence elections and policies, initiatives to address inequality will be blunted”;

(3) Voter ignorance and disinformation: As Peter Coy, the economics editor for Bloomberg despairingly noted in a review of Moyo’s book, “voters can be tribal and poorly informed”, and he cites a survey from the Annenberg Public Policy Center (U. of Pennsylvania) that found that out of 1,013 U.S. adults only a quarter could name all three branches of government. In Moyo’s words: “The proliferation of personalized media diets increasingly means that voters cling to their own facts, assumptions, and beliefs.”

By “media diets”, she means how people live in their own “bubble”, only listening to like-minded people. This raises the whole question of fake news, a complex subject covered by anthropologist Hannah Fischer Lauder in an Impakter essay, Why fake news go viral” (2016) published after Trump had unexpectedly won the 2016 elections. Now we know that it was largely a result of expert online manipulation of voter opinions, guided by the now infamous Cambridge Analytica’s techniques for targeting voters.

To these three governance problems, I would like to add a couple more:

(4) Frequent recourse to the referendum tool: I covered this problem in an article written after Brexit, “Why a referendum is a bad idea”: Brexit was a totally unnecessary mess caused by an ill-conceived referendum accompanied by poorly conducted campaigns that spread fake news about fantasy immigrant invasions; people were scared into voting for Brexit. Clearly a choice that goes against the long-run interests of the U.K. The New York Times agreed, writing that “ instead of resolving political problems, the referendums create new ones” in an article that carried the telling title: “Why referendums aren’t as democratic as they seem”.

(5) Incompetent political leaders: As of now, in a democracy there are no requirements for running for office, none at all; anyone can wake up in the morning and decide he or she wants to run for the White House; examples are easily multiplied, e.g. when Luigi Di Maio, the Five Star Movement Leader became Minister of Labor (in the previous government), this was his first job, he had never worked before; but he is alas, not exceptional. In Italy, most of the ruling class has no “real world experience”, all they’ve done, most of them, is play political games. Likewise, Trump stepped into the White House without having ever had any experience of government and exhibiting a work profile, from brankrupted real estate developer to Reality TV star, that could not in any way conceivably prepare him for the job of the presidency.

Apart from those obvious cases of lack of preparation leading to incompetence, exactly what do average politicians in democracies look like today?

Fresh data just out of the U.K., the iconic model, the “mother of all democracies”, throws light on the question and confirms that there are very real reasons to worry.

Data on gender, age, ethnicity, educational backgrounds and prior occupation of Members of Parliament elected at the 2017 General Election and how this has changed since 1979 were just published (October 2019) in a fascinating study by the British House of Commons Library.

Setting aside the aspect of age which has changed little – MPs are mostly in their 50s – several findings stand out:

- Female participation: Much improved. There were 208 female MPs elected at the 2017 General Election (32% of all MPs). This was the highest ever number and proportion. In 1979 there were 19 women MPs, 3% of the total;

- LGBTQ: Highest on record. 47 MPs elected in 2017 were openly lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans or queer, 7% of the total; This was an increase of six compared to 2015;

- Ethnicity: Much better. In 2017, 52 MPs were from non-white backgrounds, 8% of the total. This compares with 4 MPs in 1987 (0.6%), a remarkable improvement. But there is still a long ways to go: Around 14% of the UK population is from a non-white background;

- Education: Higher than the national average and a remarkable drop in the “Oxbridge” background: 82% of MPs in 2017 were graduates;

- Political experience: Only 87 MPs elected in 2017 had no previous Parliamentary experience (13% of the total): 551 (85%) had been MPs in the previous Parliament and 12 were re-elected having served in a previous Parliament;

Of all the findings, the last is the most intriguing: It suggests that what we are seeing today is a fully professionalized political class – up to 87%. And MPs are exhibiting stunningly little outside non-political experience.This is far from the ideal profile one would want in a political leader.

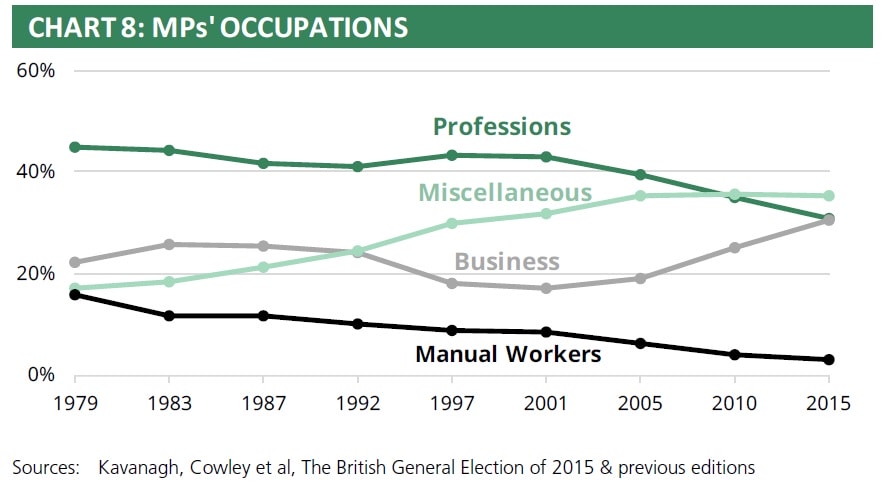

This aspect clearly comes out in the MP occupation section of the study, detailing their work experience outside of Parliament before being elected – confirming the shift towards a professionalized political class in line with the rise of lobbying power (see chart below):

- In general the proportion of white collar rose and blue collar dropped, manual workers, farmers and miners are practically non-existent today; this reflects the rise of the middle class and distribution of economic power in society today;

- What is striking is the fall of “traditional” areas producing politicians (lawyers, civil servants, teachers) and the rise of people coming from business: They went from 138 in 1979 (22% of the total) to 192 in 2015 (33%).

- But what is a matter of real concern is the meteoric rise of so-called “politician/political organizer” (classified in the “miscellaneous” category): They went from a mere 21 in 1979 (3.4% of the total) to a whopping 107 (17.1%) in 2015. Undoubtedly a reflection of the rise in interest group lobbying.

How to Fix Democracy and Get Competent Political Leaders

Moyo proposed a range of solutions that are worth going over. In brief:

(1) Prioritize policy continuity: Moyo writes: “First, policymakers should bind current governments and their successors more firmly to policies once laws have been passed.” How feasible would this be? Some of Trump’s decisions – like pulling out of the Trans Pacific Partnership in his first week at the White House – are certainly deplorable, but firmly binding a government to past policies is simply not a workable solution. Mainly because it is undemocratic: a new government reflects the will of the people as expressed in the vote and should therefore be free to pursue its own policies, even if that means breaking with the past.

(2) Restrict the financial power of the One Percent: She suggests that “democracies must implement tighter restrictions on campaign contributions to reduce the disproportionate impact of wealthy voters in determining election and policy outcomes.” Fair enough. Though it won’t be easy to implement when said politicians have packed the judicial system to favor the wealthy – as Trump has done, systematically packing the courts with conservative Republicans, both the Supreme Court and Federal circuit courts. This has caused an extreme rightward drift of the judiciary. Once the judicial system is “packed”, only Parliament can reverse the engine. But it could take a generation for a “drift” to reverse direction.

(3) Public sector salaries should match the private sector’s: The idea is to ensure quality public services; as Moyo reminds us: “large pay differentials between the private and public sectors can harm the public sector’s efforts to attract and retain the most talented people.” Indeed. Poor pay attracts losers, and worse, because politicians are poorly paid, they are easy to corrupt.

Then there is the annoying “revolving door problem”; for example, according to a report by the Advisory Committee on Business Appointments (ACOBA) who keeps track of this issue, the biggest exodus on record was of senior Tories after Labour’s 1997 triumph, with departing ministers and civil servants taking up 175 jobs between them in 1996-98.

But there’s an additional problem: As Moyo notes,“government officials might promulgate more diluted and less far-reaching regulations than they would otherwise, because they expect to make use of the revolving door and seek work in the regulated industries after their term in office”.

No doubt all this is true, but expect vested interests to push back against change.

(4) Politicians’ terms in office should match the length of the business cycle; this suggestion reflects Moyo’s training as an economist rather than a political scientist; the idea is to encourage politicians to think ahead and pursue more long-term policies that would deliver growth; on the other hand, Moyo warns, multiple terms in office should be discouraged as they will necessarily blunt dedication.

All of this is certainly desirable, but not realistic: Setting terms won’t be easy, politicians are unlikely to pass laws that they will perceive as going against their own interests.

(5) Uncompetitive election rules: Moyo has in mind the famous gerrymandering and other petty regulations that distort US elections, effectively disenfranchising large numbers of people (mostly black and other ethnic minorities, people in urban areas), thus giving an unfair advantage to the Republican party; how easily such rules can be changed is open to question;

(6) Make voting mandatory: Moyo writes, “voters are ultimately responsible for the politicians they elect and the economic decisions those politicians make. And that’s why voting must be mandatory”; she mentions abysmal low participation rates in the U.S. but fails to mention the less-than-pristine record of countries where mandatory voting is in vigour; for example, Australia, Singapore, Belgium, and Liechtenstein all share high voter turnout, but at least two of these countries are problematic: Singapore is not a liberal democracy at all but a “directed” illiberal one and Belgium can go for months, even years (the case now) as elections have not resulted in a functioning government because of intra and inter-party squabbling;

(7) Re-introduce weighted voting: The idea is to give more influence to the educated: Moyo suggests making a ballot count more or less in function of a voter’s qualifications that could be determined by a civics test or maybe by one’s profession or education. The problem here is that it’s something of a throwback to patriarchal-style 19th century democracy and even Moyo concedes that it could “no doubt be seen as jarring and antithetical to the principles of democracy”; Peter Coy slams her in his review of her book: “In the end, Moyo comes across as a well-meaning meritocrat. Democracy has its flaws, all right, but elitism isn’t the way to cure them.”

(8) Establish stringent requirements regarding who is eligible to run for office: ideally, aspiring politicians should be educated and experienced with demonstrated managerial abilities and knowledge of public administration.

Here at last, Moyo is on more solid grounds: placing requirements on political candidates would be relatively easy to achieve; one can envisage that established politicians could agree to pass even stringent requirements if the law is carefully formulated so that it’s not retro-active (laws usually aren’t): If the requirements only concerned new, incoming candidates, the political class could surely agree to it?

A Practical Suggestion: Start with What Can Be Done Right Away

Looking at how realistic Moyo’s proposed solutions are, only the last one on the list (number 8) appears feasible. All the others will either cause an immediate backlash from the powers-at-be or take time, in some cases, a generation (like reversing the rightward drift in the US Supreme Court since Justices are appointed for life).

The whole point of the exercise would be to exclude political candidates who, as Moyo puts it, “lack real-world experience”. But that’s not enough. Candidates with no public management expertise should also be excluded. Because management expertise is absolutely needed, especially for the higher-echelon jobs in government.

So, how to achieve this in practice? Consider how high level civil servants are selected. Take diplomats who (in most liberal democracies, though not all) must win a highly competitive set of exams (at least professional U.S. diplomats do – not the case of ambassadors appointed by the President in return for funding his campaign). Or better yet, take international civil servants. The requirements needed to work for the United Nations and its technical agencies are both broad and exacting: fluency in at least two languages (the agency’s official ones), an advanced education degree, two to three years’ work experience in the area of expertise.

In short, for the higher levels of the civil service, you need to demonstrate well-defined abilities (education, work experience). So why shouldn’t politicians be required to show the same? The system could be built up in such a way that the level of expertise of political candidates is tailored to their level of responsibilities in the public sector.

One could envisage two levels of entry points in a political career:

(1) at the local government level (municipality councillors, mayors, assistant-mayors etc): Here candidates would only need to have acquired an appropriate university degree and work experience (at least 3 years) demonstrating some degree of management ability;

(2) at the national level (Parliament, executive posts in government): Candidates would have to show the same profile as above (education, work experience) plus a minimum number of years, say 3 or 4, working at either the local government level or a centralized public administration.

This two-stage vetting process would tie the two levels of government, creating a coherent political career path. And ensure that the pool of politicians is made of competent, prepared people – not the case now. You have competent political leaders here and there, but they are lost in a sea of incompetent corrupt (or corruptible) politicians. People who muddle the issues and appeal to people’s self-interest and lower instincts.

Also, and this is important, the vetting process would help re-equilibrate the playing field between the public and private sectors. Bottom line, nobody in business can expect to be promoted to the jobs of CEO, CFO or COO of a respectable corporation without adequate and proven expertise. You don’t wake up one morning and decide you can run Apple or GM without having a university degree and the relevant business experience. Yet that is exactly what politicians do. Small wonder political careers attract society’s losers and rejects.

For the whole system to work, however, there is still one fundamental question that needs to be answered: What kind of education – exactly what expertise – and what type of work experience should a political candidate acquire to qualify?

The French have traditionally had an answer to that question: public administration studies. That is the mission of ENA – Ecole Nationale d’Administration – created by General Charles de Gaulle in 1945: Professionally train high level civil servants. As a result, a large proportion of French politicians are “énarques”, i.e. ENA graduates. After 70 years of operation, three presidents, seven prime ministers and many ministers have come out of ENA.

Has this given good results? Looking at France’s turbulent political history since World War II, it is hard to feel optimistic. Yet there is little doubt that French politicians are often remarkable, people like former President Valérie Giscard D’Estaing or current President Emmanuel Macron come to mind – and perhaps they are, on average, more remarkable than in many other countries. If they haven’t done better, it is in large part due to the overall political situation, with an opposition that never hesitates to exploit people’s credulity and self-interest. Strikes currently crippling France illustrate the point: Macron’s proposed pension reform, while totally rational and relatively benign, is rejected by unions.

In any case, ENA has been accused of producing elitists with the wrong kind of expertise. And that brings us back to the question. If aspiring politicians and civil servants are going to get a degree in public administration, what kind of administration should they study?

To put it another way: Can we agree on the ultimate goal of public administration? For Dambisa Moyo, she has no doubts that it is about achieving “economic growth”. But other political thinkers disagree, notably Mariana Mazzucato , the “scariest economist” according to the Times, perhaps because she has called for a total overhaul of economics.

In several best sellers, among them The Entrepreneurial State – Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths (2013) and The Value of Everything, Making and Taking in the Global Economy (2018) Mazzucato is shaking neo-liberals in their dearest free-market convictions, calling for a total rethink of the role of the State. What is required according to her is a complete reshaping of the market economy and recognition of the value of public enterprise.

She reminds us that the SDGs exist, they have been voted for unanimously at the UN and it is time, she says, to follow through, with the State launching green projects, as she explains in this diagram:

screenshot – from the video presentation of her book made at the UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, 10 July 2018

There is no doubt that fixing democracy also means rethinking the role of the state. But to be practical: Why not start with what is easy to change, introduce a simple requirement that political candidates should be educated – any university degree will do – and have some relevant work experience, showing an ability to manage and lead?

It’s the first step and it will make all the other steps easier to take. Once the pool of politicians has improved and a majority of politicians finally develop a “sense of the State” instead of pursuing their own self-interest, there will be less push-back on all the other changes required to fix democracy.

We’ve had too many incompetent leaders for too long. How about trying to have competent leaders for a change?

Featured image: Photo by U.S. Department of State (IIP Bureau) taken on August 19, 2014 CC BY-NC 2.0