In these pandemic times, many people may ask why we should bother with antimicrobials when we know what the problem is and that they do not treat COVID-19? The answer is that a person with COVID-19 is simply more difficult to treat and more vulnerable to serious consequences if they have developed antimicrobial resistance.

To start with, COVID-19 globally has infected over forty-two million people (8.6 million in the U.S.) and caused over one million deaths (over 220,000 in the U.S.). And these numbers are growing.

This is a novel virus, not yet well understood, and it has generated huge amounts of money and research to come up with vaccines and therapeutics. While many killer diseases such as HIV/AIDS, TB, or the common cold, have preventive approaches or therapies to ameliorate the affect, i.e. strengthen resistance and accelerate recovery, they do not have vaccines.

With technology, new science techniques are at work in the case of COVID-19 so that we may end up with one or a few safe and effective vaccines. Even once there is a vaccine solution, this novel virus is likely to be with us for the foreseeable future, and therefore therapeutics will be needed to handle different levels of COVID-19 infections.

Many different therapeutic approaches are being explored, including the application of laboratory-produced antibodies, the synthetic versions of the natural weapons produced by a person’s immune system. For example, Prometheus, a collaboration between academic laboratories, a U.S. Army medical research institute, and a private company, is studying whether an all-purpose antibody approach to multiple coronaviruses is feasible.

Separate vaccine trials are underway to find a safe and effective vaccine – currently, more than 100 COVID-19 vaccine candidates are under development, according to WHO. Despite the risk of failure, several pharmaceutical companies are preparing production lines to produce hundreds of millions of doses.

With respect to coronavirus therapies, here too, multiple efforts are underway to research, develop, and bring effective treatments against COVID-19 to market.

The role of antimicrobials in COVID-19 therapies

Old and new versions of antimicrobials have been with us for many years. They have been the “go-to” therapeutics for many kinds of infectious diseases and infections and have saved millions of lives.

Antimicrobials primarily treat bacterial, fungi, and other parasites. But there’s a problem. With use (and abuse) overtime, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) happens when germs like bacteria and fungi develop the ability to defeat the drugs designed to kill them.

The germs are not killed and continue to grow, the parasites change over time and no longer respond to medicines. As a result, infections are harder to treat and there is an increased risk of disease spread, severe illness, and death.

The threat of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria and other superbugs is worsened and can become critical when patients admitted to hospital with covid-19 receive antibiotics to keep secondary bacterial infections in check. Further, a COVID-19 infected person treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics to address an existing infection, or a coinfection, can significantly affect the ability of that individual’s system to deal with COVID-19.

Growing outbreaks of COVID-19 in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) with weak health systems are likely to result in an increase in the use of antimicrobials.

Antibiotic treatment of bacterial pneumonia is an accepted and familiar LMIC clinical practice and because of the similarities with the flu and other fevers, it will be difficult for these practitioners, especially in rural and semi-urban settings, to differentiate from COVID-19 symptoms. Where medical infrastructure, equipment, and human capacity is not at hand, the health professional will reasonably fall back on relying on what was reliable in the past, namely antibiotics.

With these very real, on-the-ground constraints, some people with viral infections are likely to receive unnecessary and ineffective antibiotics, adding to an already existing problem. And, when such treatments do not work and many do not get better, this could have an additional negative knock-on effect. It could further undermine trust in the health workforce and the health system.

It is also possible that widespread and heightened attention to COVID-19 could result in greater trust in healthcare systems, improvements in health infrastructure and the health workforce, and in generating resources for health research.

Data from five countries found that 6-9% of COVID-19 diagnoses are associated with bacterial infections (3-5% diagnosed concurrently and 14.3% post-COVID-19), with a higher prevalence in patients who required intensive care. A U.S. multicenter study reported that 72% of COVID-19 patients received antibiotics even when not clinically indicated. This can further result in AMR, worsened due to the overuse of antibiotics in humans.

Years before 2020 there was widespread recognition that the overuse and resultant resistance was an important health concern.

Several important meetings and recommendations were made at the international level. In 2016 AMR was the subject of a Special UN General Assembly High-Level Meeting. This was followed by recommendations of the UN Interagency Coordination Group on AMR which put forward a “One Health” roadmap to intervene on AMR at the interface between human, animals, and the environment.

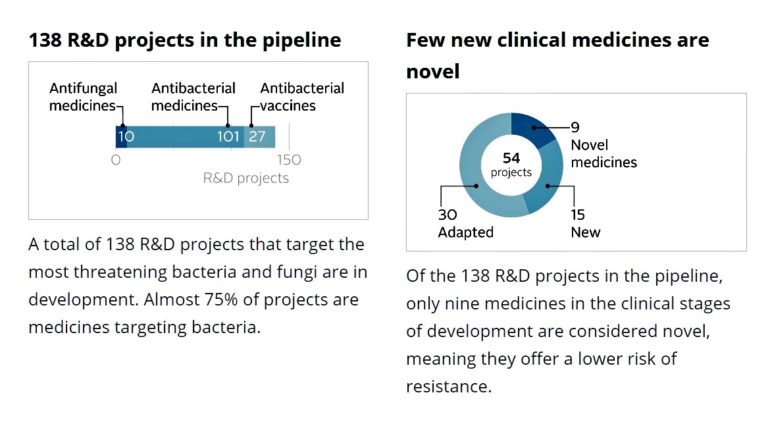

In 2020 the World Economic Forum considered its Antimicrobial Resistance Benchmark Report. Findings showed that they were “signs of progress” in antimicrobial resistance research but not “at the scale needed”:

Actions were also taken at the national level.

In the United States, the U.S. Presidential Advisory Council on Combatting Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria in 2019 proposed new targets for 2020-2025.

In 2020, the Indian Government introduced legislation to place limits on antibiotic residues released into the environment at pharmaceutical manufacturing sites.

Fish farming saw advances. Norway implemented a vaccine to prevent a major infection in salmon farming resulting in reduced antibiotic us by nearly 100%. Chile’s salmon industry pledged to reduce by 50% antibiotic use by 2025.

In the U.K. human antibiotic use decreased by over 7% between 2014 and 2017. Further, the UK launched the world’s first experiment to pay for antibiotics by subscription rather than per pill, which is hopefully to provide incentives for two new antibiotics by 2022.

In short, prospects were promising for heightened attention to AMR by individual countries, the pharmaceutical industry, as well as the research, and investment communities. Then when COVID-19 affected everyone and everywhere, the media and public attention shifted.

From AMR to COVID-19

The focus of those who could prioritize AMR understandably turned to the COVID-19 pandemic. By the Spring of 2020, it was universally “the” priority. The extent to which global cooperation translated into the common cause is reflected in the “Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-Accelerator)”. Launched at the end of April 2020, it requested commitments of over $31 billion in a year from governments, multilateral financing institutions, non-profit organizations with participation from health organizations, scientists, businesses, civil society, and philanthropists.

ACT-Accelerator is organized on four pillars, representing the key response aspects, namely:

- diagnostics led by FIND and the Global Fund;

- therapeutics by UNITAID and the Wellcome Trust;

- vaccines by the Vaccine Alliance; and

- health systems (World Bank and The Global Fund).

Each pillar is critical, and many partners have joined in the effort. The U.S. has not participated, ostensibly because WHO is the organizer, nor has Russia. Recently the People’s Republic of China has joined the vaccine commitment. The jury is still out as to the extent to which major health research and production countries and private sectors will eventually collaborate.

At this point, the ACT-Accelerator is mostly in the planning phase, a work in progress.

In the best of times, the $31 billion sought in new commitments would be a “reach”. With the devastating economic impact on countries, it is much more difficult for heretofore generous national constituencies to provide external assistance: Legitimate demands at home draw more heavily on significantly reduced public sector resources.

That said, the extent of human and economic hardship interdependence has meant countries and institutions have been digging deep to respond and that is a promising development.

Hopefully, the COVID-19 pandemic will be dealt with effectively in the next few years. Once reasonably contained, there would be the opportunity to again focus on antimicrobial resistance and elevate it back to where it should be: A global multisectoral priority, one touching several of the Sustainable Development Goals. Unfortunately, if the past is prologue, it is hard to be optimistic. But maybe “this time it will be different”.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com contributors are their own, not those of Impakter.com.

Featured Image: UK Government announces £30 million funding in AMR research, May 22, 2018. Source: Open Access Government org.