To an idle observer dropping in from Outer Space, the UN Security Council is the strongest organ of the United Nations.

Tasked with maintaining peace among nations, it has been given weapons of war. When it passes a resolution, it can send troops, the blue-helmeted UN peacekeepers or “blue berets”, and force peace on belligerents. Blue berets belong to member nations’ armies, but taken together, they constitute a hefty, permanent UN force.

Tasked with maintaining peace among nations, it has been given weapons of war. When it passes a resolution, it can send troops, the blue-helmeted UN peacekeepers or “blue berets”, and force peace on belligerents. Blue berets belong to member nations’ armies, but taken together, they constitute a hefty, permanent UN force.

At this point in time, over 110,000 military personnel are permanently deployed around the world in “hot spots”, currently in 15 “missions”.

This level of intervention dates to the collapse of the Soviet Union (1988): the number of resolutions doubled, the peace-keeping budget increased by a factor of ten. So far, there have been eight major missions, with only two notable failures, Somalia and Bosnia. A respectable record nonetheless. The biggest failure however was caused by lack of intervention. This happened in 1994, when one of History’s worst genocide was perpetrated in Rwanda.

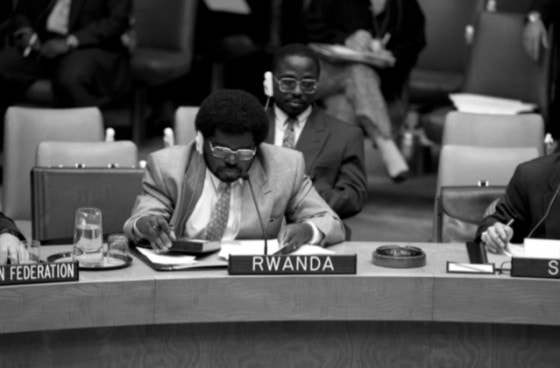

In the photo: UN Security Council Meets on Rwanda 08 June 1994

The Security Council can do more than send troops. It can refer bloodthirsty dictators and generals responsible for “crimes against humanity” to the International Criminal Court in The Hague, a major cog in the UN machinery (done for Darfur, Libya). It can call for an arms embargo (15 on-going embargoes, including Somalia, just extended). It can send staff to oversee elections and support the democratic process as it did in Afghanistan or the Sudan.

In the photo: Peacekeeping Chief Visits South Sudan Hervé Ladsous (right), Under-Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations, arrives in Bor, South Sudan.07 July 2013

In the photo: Peacekeeping Chief Visits South Sudan Hervé Ladsous (right), Under-Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations, arrives in Bor, South Sudan.07 July 2013

You get headlines in the press like “the Security Council can and must act on Syria” or “Biting words but no action at Security Council”. Yes, if the UN Security Council sets its mind to it, it can do a lot.But it must set its mind to it. It cannot act if it hasn’t passed a resolution to do so.

This is the hitch. Yet its small and nimble size suggests it should be effective. With only fifteen members aboard, matters can be meaningfully debated unlike the 193-strong UN General Assembly. If you want a quick decision, forget the General Assembly, you’ll only get a cacophony. The system is not unfair: Security Council members are chosen on a rotating basis so that over time every country gets a chance to sit for two years on the Security Council. Except for the five “permanent” members, the United States, Russia, China, the UK and France.

The permanent members have veto power. They are the only ones who truly exercise world power.

A case in point, Syria. Nothing can be done to solve the Syrian crisis because of the Russian and Chinese veto. When those two countries stop supporting Bashar Al Assad, something might get done. The problem: the balance of power in the Security Council does not reflect the world’s current balance of power. Currently, three of those five permanent members are indisputably world super powers, the UK and France are not. When the Security Council was established and had its first session in 1946, the world, emerging from the worst war in History, was vastly different from what it is today. Let’s count the changes.

In the photo: UN Security Council Meets on Rwanda 08 June 1994

First, consider the UK and France. They were on the side of the victors but they were destroyed, mere shadows of their former historical self. Like the mythical phoenix, they rose from their ashes, but so did the World War II losers, Germany and Italy. Check, those two countries want permanent seats on the UN Security Council.

Next, the Third World. It is no longer third, many countries, the so-called BRICS, are knocking on the First World door. With rapid economic growth, there are new “big players”, Japan and India in particular. Check, but there’s no stopping the candidates. Mexico, Brazil and others emerge carried by economic growth, not to mention new demands from Africa and muslim-majority countries that all want a permanent voice.

Finally, Europe. What had started as a modest “common market” with six countries has morphed in a 28-strong European Union that cannot be ignored. Check, but what about the UK and France’s permanent seats?

The way out. Many solutions are proposed to reform the system, including expanding the number of permanent seats and adding a new category of seat (to last longer and be renewable). Reform requires agreement of two-thirds of member states and all five permanent members. Germany, Brazil, India and Japan have a foot in the door, but it’s not opening quite yet. Everybody officially supports change, yet the super powers (the US, Russia and China) are in a quandary, while France and the UK prefer the status quo. Expect the status quo, unsatisfactory as it is, not to change anytime soon…