Since abruptly lifting lockdown restrictions in early May 2020, the Serbian government has held an election and has authorized an international tennis tournament as well as a football cup final with up to 25,000 spectators. Through decisions like these on top of public statements and abnormally low official numbers of COVID-19 deaths during the pre-election period, citizens were assured by government officials and crisis team doctors that the situation was under control and that the virus had been “defeated” — but only until the election. Then the deaths spiked and it became “alarming.” It seemed like a joke. Or was it a miracle? Far-left to far-right to religious groups, students to the elderly, sports hooligans to the academia, Serbian citizens were outraged and began taking to the streets as part of Europe’s first major pandemic-related unrest.

“We can only say what we know, and we can only act on what we know,” said World Health Organization (WHO) Director-General Dr. Adhanom Ghebreyesus as part of his opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 this April.

Serbian citizens believe their government neither said nor acted on what it knew in terms of the pandemic crisis. Instead of acting on what it knew about the severity of the situation — the rising cases, the lack of beds, respirators, medical equipment — the government acted on its interest to open everything up in time for the election, which meant acting against what it knew.

“And so the citizens of Serbia,” an article on Nova.rs read, “will once again pay the price of negligence and irresponsibility from the government that disregarded the pandemic for its own interests, announcing victory over it.”

President of Serbia Aleksandar Vučić helped to confirm this conviction in a television appearance on July 7, about two and a half weeks after the election. That summer evening he admitted for the first time since lockdown measures were lifted in mid-March that the pandemic situation was “alarming” and that all hospitals in Belgrade were “basically full.” He blamed “irresponsible citizens” and announced new lockdown restrictions for the upcoming weekend. Hearing this, many in Belgrade began walking out onto the streets and gathering spontaneously in protest even before the president’s speech ended. Many more followed throughout the night and the couple of days to come.

Answering my question about the protest, an analyst and former BBC war journalist who wished to be referred to as a “fellow citizen” said that what we saw was a “visceral reaction of people living in a society that is totally devasted by a captured state.” Meanwhile Deutsche Welle offered another angle: “Serbs have gone out onto the streets to demonstrate because they feel cheated.” And indeed, they do. Cheated.

The first curfew since World War II was imposed on a Wednesday night in mid-March. The measures were among Europe’s strictest, and several Members of the European Parliament wrote a letter about them to the European Commissioner. They referred to them as severe and disproportionate and said that they restricted human rights “apparently not in order to prevent the spread of COVID-19, but to impede freedom of expression and free movement.”

Serbs shared these fears. Not unlike in other countries around the world, the people believed that their leaders took advantage of the coronavirus crisis to gain a firmer grip on power. But unlike in most countries, the Serbian government imposed what in Serbia is called a “police hour,” otherwise known as a curfew. At one point, people older than 65 were forbidden from leaving their homes for 34 days, except for three hours on two Sundays between 4 am and 7 am.

The rest of the population received a different treatment. No one was to leave their home between 6 pm and 5 am on working days for over a month and a half. These hours varied on weekends. It began with 20 hours and grew longer and stricter with every new weekend until the citizens faced an 84-hour lockdown between Friday evening and Tuesday morning, punishable by arrest, a night in police custody, and a fine of up to 1,270 EUR — at least twice the average salary.

Then these measures were lifted, too suddenly as many doctors remarked and as the current outbreak implies, and Serbia went from having one of Europe’s most extreme to most relaxed pandemic measures practically overnight.

Life had quickly returned to its pre-pandemic state and, within weeks, universities, restaurants, bars, and nightclubs were all up and running again. Eleven days before the election, a football cup final was opened to spectators and was described by France 24 as the “largest gathering of that kind in Europe since the beginning of the pandemic.” And then there was the only election in Europe that, as Academic Dušan Teodorović remarked, has not been canceled in the spring of 2020.

Official voter turnout statistics show that around half of the population did not vote (the majority of opposition parties boycotted the 2020 election). The other half left their homes and voted at their polling stations.

But “it was a lot safer than going to the store for five minutes,” President Vučić referred to this coronavirus risk in an interview.

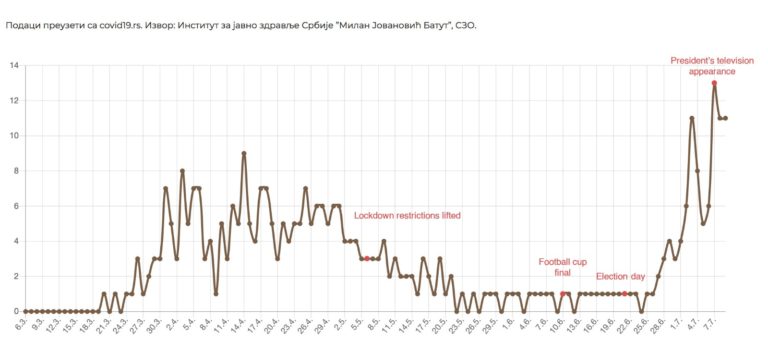

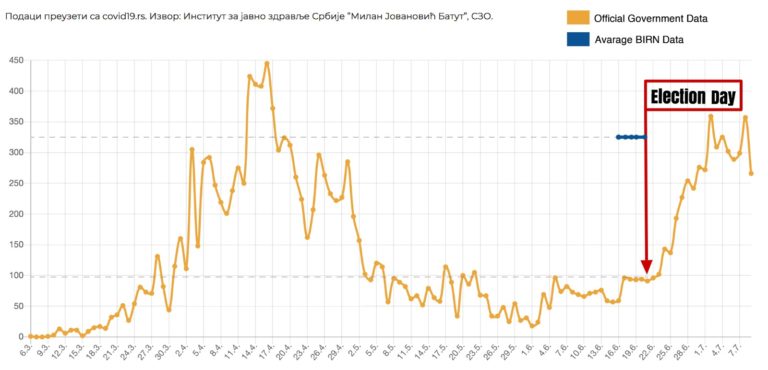

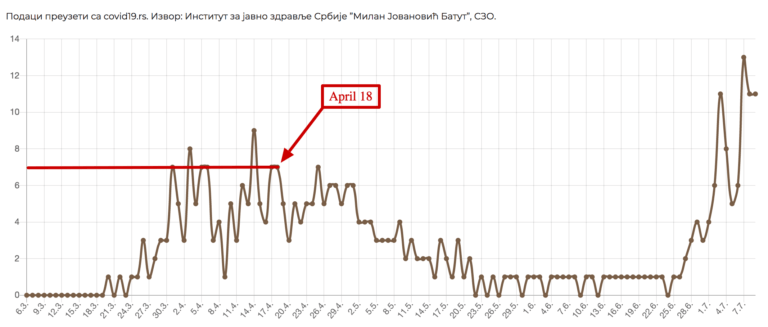

The official government graph above shows the official number of COVID-19 deaths per day in Serbia since the start of the pandemic and can help to clarify why Serbia feels cheated and accuses the government of omitting the truth. According to it, the official number of coronavirus deaths per day showed at most one death for about four weeks leading up to election day. Meanwhile the official number of confirmed COVID-19 cases never ceased to rise, reveals another such chart from the official government COVID-19 reporting website.

Four days before the election, President Vučić encouraged citizens to vote: “You just come, vote, and leave. You’re not exposing yourself to any risk.” Four days after the election, the number of deaths per day began to grow. Two weeks later it was higher than ever before. Associate Research Professor at the Institute of Physics Belgrade Dr. Milovan Šuvakov calculated the probability of this official scenario to be 1 in 4 million.

And thus the Serbs faced a choice: To believe the official government COVID-19 statistics and that what had happened could only happen once in every four million such pandemics — or not to? Was it a miracle or was it lies?

Non-profit NGO Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN) argues that it wasn’t a miracle. Having analyzed data from the Serbian Institute for Public Health “Dr. Milan Jovanovic Batut,” they uncovered data showing higher numbers of COVID-19 deaths and cases than those the government revealed to the public and global organizations.

Official government data shows 97 new COVID-19 cases per day during the couple of days leading up to the election day. The data BIRN found in the Institute for Public Health says there were 300-340. Government says that 244 coronavirus patients died in total by June 1. BIRN says the Institute for Public Health says 632 people died during that period. On May 6, the day before restrictions were lifted, government data showed three deaths of COVID-19. BIRN revealed twice that number.

Once this difference has been pointed out in public, Prime Minister Ana Brnabić appeared on national television and explained:

Let’s say I have symptoms. I go to a COVID hospital, get tested and receive results. I’m positive. I start experiencing complications and go to the infective clinic. As soon as I’ve received a positive test, they’ve entered my name into the COVID-19 database. On my way to the clinic, I get hit by a bus. I die. I am, of course, deceased in this database. Do you think that I should be listed among those who died of COVID-19?

On April 12, when official government data showed six coronavirus deaths, BIRN claimed that there were 38 deaths in the Institute for Public Health database. BIRN editor Milorad Ivanović publicly stated that they had reached out to Prime Minister Brnabić, Minister of Health Zlatibor Lončar, the Serbian Institute for Public Health director, and Dr. Predrag Kon, COVID-19 crisis team member and the government’s chief epidemiologist, all via email, phone call, and SMS, asking for comments on these differences and receiving no response.

“We’re going to loosen up the measures after the Easter holidays since this virus is dying out in most of Serbia as the data shows. And that is a fact,” said crisis team doctor Predrag Kon on April 18. Seven people officially died of COVID-19 on April 18. Until then, seven was the third-highest number of deaths per day since the beginning of the pandemic.

The health workers couldn’t buy the miracle scenario either and eventually began speaking out all across the country. In an emotional and disturbing speech on a television talk show, President of the Doctors and Pharmacologists Union of Serbia Dr. Rade Panić summarized the thoughts of those bearing the heaviest burden:

Citizens of Serbia must urgently understand that they have been deceived so that the election can take place, that the lockdown measures have been lifted unjustifiably — they needed to be lifted gradually; that we’re short on medical workers and don’t have the proper safety equipment nor the adequate means to treat patients. I’m begging citizens to take this as seriously as possible and to no longer believe politics or the crisis team, for we no longer have the means to help them.

Whereas in France the medical workers’ unions protested because the government’s new deal that would provide health workers with pay rises did not go far enough, in Serbia the president appeared on national television and said:

“That president of the health workers union — he is no president of no health workers union, but of one of the smallest unions…and a man who says the most horrific things about his country and who told the worst lies.”

The Doctors and Pharmacologists Union of Serbia denied this statement as well as five other statements the president made during that single interview in a public letter to the national television. “Dr. Rade Panić,” the letter read, “is the president of the Doctors and Pharmacologists Union of Serbia (SLFS). SLFS is not “one of the smallest” nor is it “no” union as the president says.”

In Vojvodina, a northern province, two doctors and a nurse from the local hospital had reached out to journalist Ana Lalić. She spoke to them and wrote an article about the poor conditions at the hospital. The piece included their anonymous confessions and an official statement by the president of the province parliament revealing that every fifth COVID-19 patient in the province was a health worker. It also described hospital conditions as “entirely chaotic” and reported a “chronic shortage of basic equipment.”

Lalić published the article on the morning of April 2 and was arrested a couple of hours later for allegations over causing panic and unrest. She was ordered a 48-hour arrest pending interrogation but was released the following morning after pressure from journalist organizations and comments expressing concern from EU officials. When Lalić spoke out the following day, she said that she wasn’t the only journalist who had that information and that the hospital employees received warnings from the hospital committee that they would be sanctioned if they communicated with the media.

At first, this version of the state of things was only known to patients, health workers, or people who knew either of those. But as time passed, more evidence began surfacing as videos, photos, health workers’ confessions or tweets. And the more evidence there was, the more citizens outside the health sector began speaking out, too.

Until the morning after the election day, citizens knew for two possible scenarios: Either the government purposely concealed the true data from both the crisis team and citizens, or both the government and crisis team omitted the true data from the public. Dr. Kon and crisis team immunologist Dr. Janković, neither of whom had denied the data BIRN uncovered, assured the public that they only had access to official government data — the same numbers as the public.

But no sooner than the morning after the election, both Dr. Kon and Dr. Janković warned about another outbreak, even if there hasn’t been any sudden change in the number of new cases, daily new cases, or daily new deaths for about a month. “The epidemiological situation of COVID-19 in Belgrade is threatening again,” Dr. Predrag Kon addressed the public via a Facebook post on the morning after election day. “Due to students returning to their homes, the threat may spread throughout Serbia in July.” That same morning Dr. Janković appeared on national television and confirmed that “there has been another outbreak, at least in Belgrade,” making it clear, at least to citizens, that both the government and the crisis team were concealing the truth.

By the time President Vučić appeared on television on July 7, most people had already long known about all of this and were familiar with the true situation. They were just waiting for the government to admit it and take responsibility. But Vučić blamed the citizens and announced another curfew, sparking this series of genuine and spontaneous protests.

Answering a question on live television about why he was demonstrating, protestor Petar Djurić Djufa — in tears from sorrow, teargas, or both — put into perspective the cruelty in the government’s pandemic response:

Pops, this is for you. You died because there were no more respirators, and I still haven’t received the documentation that you died of coronavirus. There were no more respirators in the Zemun hospital while they kept bragging about having so many respirators that we could give them out to charity. Djufa Ljubiša Djurić — I love you so much. Pops, this is for you.

The following day this protestor was all over the pro-regime media, which is most media, with his “violent,” teenage past in the spotlight, mentioned in most headlines of the several most sold newspapers in one form or another. “This young man,” one newspaper wrote, “is otherwise known as the bully from Majdanpeka who harassed his history professor in high school.” Perhaps most mercilessly, one tabloid claimed that he had “filmed his naked father while he was taking a shower and then brought the video to school and showed it to everyone.”

Petar Djurić was another citizen who spoke out in hopes of exposing the true pandemic situation. Shortly after his father passed away — around three weeks before the protests — he posted several sentences on Facebook and uploaded his father’s medical report, which confirmed that the man was waiting for a respirator when he died. “That same day,” Petar said in an interview, “the leaders of the [ruling party] in Majdanpek called me and offered to pay for the funeral if I would take down all posts mentioning the current government. Of course, I declined.”

The government’s reaction to Petar’s deeply moving outcry on television was sadly just as swift. Already the next morning, Serbian Minister of Health Zlatibor Lončar publicly denied the lack of respirators and said that it wasn’t true. “Last night,” President Vučić also addressed the mourning protestor the following day, “a man whose father passed away from coronavirus was portrayed as a hero. This is about a notorious lie — that there were no respirators.” Vučić went on to refer to Djufa as a “person with a very bad past, convicted of crimes,” and concluded: “Don’t present people like these as heroes, we know who we’re dealing with.”

This approach on the micro-level paints quite the image of how Serbia has been governed on the macro-level over the years. But while the people are already long used to all this, the consequences have never before included public health and peoples’ lives on a broader scale. And if this new dimension doesn’t affect the ruling party’s power and stability, what will?

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Serbina people protesting in front of the parliament building, July 7, 2020. Featured Photo Credit: Vladimir Paunović