EDITOR’S NOTE: THIS PIECE IS PART OF A SERIES EXPLORING THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS (SDGS) SEE THE INTRODUCTION TO THE SERIES HERE.

Water is integral to the 2030 Agenda

Water is a vital resource connecting all life on the planet. As such, it has the potential to drive myriad feedbacks related to both public and ecosystem health. These range from effects on the quantity and quality of the physical water supply to increases in the prevalence of water and foodborne disease. Threats to water security are absolutely  consequential, especially with respect to a growing global population and climate change. Therefore, water is an integral part of the 2030 Agenda, specifically targeted in SDG 6: Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. Having access to safe drinking water and adequate infrastructure for sanitation provides a strong foundation from which communities can become empowered and economies can grow at the local and regional scale.

consequential, especially with respect to a growing global population and climate change. Therefore, water is an integral part of the 2030 Agenda, specifically targeted in SDG 6: Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. Having access to safe drinking water and adequate infrastructure for sanitation provides a strong foundation from which communities can become empowered and economies can grow at the local and regional scale.

However, managing water resources at scales that are effective remains a challenge, especially without sufficient infrastructure that ensures equitable distribution and monitoring. To help achieve SDG 6 incrementally by 2030, a number of targets have been adopted to draw the roadmap to achieving SDG 6.

Note: Some of the language within the targets is such as “substantially” or words like “support and strengthen” are subjective; as a result, monitoring these targets are more of a challenge.

- 6.1 By 2030, achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all

- 6.2 By 2030, achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations

- 6.3 By 2030, improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimizing release of hazardous chemicals and materials, halving the proportion of untreated wastewater and substantially increasing recycling and safe reuse globally

- 6.4 By 2030, substantially increase water-use efficiency across all sectors and ensure sustainable withdrawals and supply of freshwater to address water scarcity and substantially reduce the number of people suffering from water scarcity

- 6.5 By 2030, implement integrated water resources management at all levels, including through transboundary cooperation as appropriate

- 6.6 By 2020, protect and restore water-related ecosystems, including mountains, forests, wetlands, rivers, aquifers and lakes

- 6.a By 2030, expand international cooperation and capacity-building support to developing countries in water- and sanitation-related activities and programmes, including water harvesting, desalination, water efficiency, wastewater treatment, recycling and reuse technologies

- 6.b Support and strengthen the participation of local communities in improving water and sanitation management

Issues Are Water Soluble

A subtle entity unique in its ubiquity, water can be easily placed out of focus. Water is everywhere. But, is it? The constant comfort of turning a knob to fill our cups with fresh water is indeed a privilege one could strive for and one that is associated with living in fully-developed societies.

The bold truth of the matter is that water is not ubiquitous everywhere. In fact, almost 80% of the global population resides in regions of high water stress due to competing human demands and other stressors such as drought. Therefore, economic issues, public health issues, and issues of conflict are indeed water soluble, in that access to water or lack thereof directly or indirectly influences the outcome or trajectory of each of these challenges. In the context of the SDGs, they are a nexus within the SDGs must act, for the intersectionality of the SDGs is non-trivial. Each issue dissolves into water, creating an often more complex solution of nuanced challenges.

IN THE PHOTO: SECRETARY-GENERAL BAN KI-MOON (RIGHT) IS GUIDED BY A LEADING SCIENTIST ON THE STUDY OF PEAT FIELDS, IN AN AREA AFFECTED BY DEFORESTATION IN CENTRAL KALIMANTAN PROVINCE, INDONESIA. THE UN PROGRAMME ON REDUCING EMISSIONS FROM DEFORESTATION AND FOREST DEGRADATION (REDD+) OPERATES PROJECTS IN CENTRAL KALIMANTAN AND ASSISTS IN THE CONSERVATION AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF ITS FORESTS. PHOTO CREDIT: UN PHOTO/MARK GARTEN

The quantity and quality of water are heavily influenced by the compound effects of human land use and climate change, such as conversion of forested land to agriculture and flood-induced soil erosion.

This state of affairs highlights the need for management of water resources based on a deeper understanding of the influence of human land use and climate variability on water provision and how this relationship may be changing under a changing climate. The difficult reality is that our global water supplies are changing and, in many circumstances, compromised through overexploitation, pollution, and land degradation. Reconciling this changing landscape whilst prioritizing access to water and sanitation as a human right, as laid out in SDG 6, is a daunting challenge that we must achieve by 2030. To examine how SDG 6 may translate on the ground and grasp a deeper understanding of the level of regional-based complexity with respect to water, consider the following case studies.

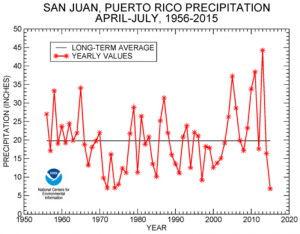

Lessons Learned in Puerto Rico: Drought and an Economic Crisis

In 2015, the island of Puerto Rico suffered an “extreme drought” according to the NOAA classification. In June of 2015, nearly 55.1 percent of Puerto Rico experienced abnormal dryness, while a third of the island was experiencing moderate to severe drought. During this time period, areas of Puerto Rico observed its driest May on record with only 0.27 inch (6.9 mm) of precipitation. These patterns of dryness were also observed in record low streamflow, directly having an impact on local water supplies. Furthermore, a comparison of 2015 April-July precipitation means to long-term averages, clearly illustrates the severity of the 2015 drought in Puerto Rico.

In addition to an extreme drought, Puerto Rico is mired in an increasingly challenging financial crisis, with both the island and public corporations owing roughly $72 billion in loans. Governor Alejandro García Padilla has repeatedly warned that Puerto Rico is close to defaulting on this debt and has already missed several payments. The U.S. Congress has made little progress in helping Puerto Rico with its economic woes, further impeding the implementation of a clear solution. What is clear is that forcing the island to pay its obligations may result in the collapse of local institutions, lead to higher unemployment, and further degrade critical services. Fortunately in June, U.S. Congress passed the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act, or PROMESA, just before defaulting on a $2 billion payment, which allows the territory to finally restructure its debt. Although it creates an oversight board which critics suggest will undermine the democracy of Puerto Rico, the bill does give Puerto Rico a chance to move forward.

During the drought, approximately 160,000 residents and businesses on the island had their water turned off for 48 hours and subsequently turned back on for 24 hours. This lead to documented chaotic practices of collecting water while it was turned on and storing it for basic sanitation needs (SDG 6.1, 6.2, 6.4). An additional 185,000 residents went without water for 24-hour cycles, and 10,000 were on a 12-hour cycle of rationing water. Therefore, an estimated 340,000 households and businesses or 28% of the island’s population went without water for a time during the drought, with frequent water cuts lasting up to 48 hours.

Here in Southeastern Puerto Rico the drought we’ve experienced in the past few years seems to be related to a large number and extension of wildfires. This past year, the PR Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DNER) started placing signs in open areas especially prone to fires. The DNER in coordination with the PR Aqueduct and Sewer Authority (PRASA) implemented water rationing of the south coast aquifer in Salinas and Guayama. More efficient management of the aquifer such as recharge ponds, moratorium on further construction and requiring the Aguirre Power Complex to use an alternate water source or alternate generation methods (water-energy nexus) could lead to more efficient use of water resources.

-Ruth Santiago J.D., Community Lawyer

It is clear that, these drought conditions are compounding the economic crisis, costing the Puerto Rico water authority an estimated $15 million a month due to reduced payments and increases in operating costs. These costs come on top of the water authority’s $5 billion estimated debt.

Complicated by Climate Change

Climate change is only further complicating this story and model projections paint an ominous picture when it comes to water stress for much of the Caribbean.

Specifically, models predict rapidly increasing surface temperatures for large areas of the tropics. Some predictions suggest a reduction in annual rainfall by as much as 50 percent, largely due to a continuously drier rainy season over the next century. This suggests we should expect more frequent and prolonged drought conditions for Puerto Rico and the rest of the Caribbean.

Extreme-lasting drought conditions are likely to place a strain on the water budget of tropical forests, which are intimately linked to water yield and quality for many communities within Puerto Rico and other regions within the tropics. Therefore, in addition to challenges related to infrastructure and an economic crisis, there are growing negative impacts of forest degradation to water supplies, which normally help safeguard water supplies against threats such as drought. But, what is the role of forests, exactly?

The Role of Forests

Forests are an important governing factor of watershed ecosystem services (SDG 6.6). Specifically, the health and structure of forests have a large impact on the quality and quantity of watershed ecosystem services, such as improving extractive water supply and in-stream water supply, mitigating water damage, and providing water-related cultural services such as recreational activities.

More than 70% of all remaining tropical forests in the world are second-growth forests on former agricultural or logged lands, and these may be responding differently to climate change. In a carbon context, secondary-growth tropical forests are estimated to account for approximately 40 percent of the terrestrial global forest carbon sink.

Therefore, the response of these forests to a changing climate is unknown; yet, given the amount of carbon stored within these forests, they are a priority when it comes to forest management. But management should not consider carbon alone, instead, it should take into account the multiple services provided by forests, including water.

IN THE PHOTO: THE PHOTOGRAPH WAS TAKEN EARLY IN THE MORNING WHEN FARMERS GO TO PADDY FIELDS IN THE MOAS VILLAGE, CENTRAL JAVA, INDONESIA PHOTO CREDIT: UNITED NATIONS FORUM ON FORESTS PHOTO COMPETITION

The relationship of forests and water is still relatively unclear and remains contentious within the scientific community. Although it is established that healthy forests increase water quality, the degree to which forests regulate the quantity of water is disputed.

There is evidence suggesting that the presence of forests enhances overall water provision, while conversely, studies have also observed forested areas decreasing overall water supplies as the demand for water by the trees outweighs their positive effect on soil conditions.

Related article: “A SHORT HISTORY OF THE SDGS“

Therefore, additional research is needed to gain a deeper understanding of the precise role forests have in governing water supply for communities. Forest management informed by this research, may provide insight into developing tailored strategic planning at the local level needed to maintain both water quantity and quality.

How does water relate to public health and disease?

Key to achieving SDG 6 is also successful implementation of sanitation infrastructure. A lack of of this infrastructure can lead to numerous public health crises, including food-borne trematode disease (SDG 6.2, 6.3).

Currently, there are around 750 million people at risk of foodborne trematode disease, or 10 percent of the global population. Unfortunately, these illnesses are largely related to poverty. Therefore, the populations most at risk reside in developing nations, particularly in rural areas, often with limited sanitation and water infrastructures.

Many trematode diseases are food- and waterborne; therefore, understanding the ecological dynamics of the areas of infection along with environmental policy is essential (SDG 6.6). This requires bottom-up co-created regional health initiatives that are sensitive to local cultural needs and include all stakeholders (6.b).

IN THE PHOTO: LITTLE GIRLS FROM VEMASSE AFTER HEAVY RAIN CROSSING THE RICE FIELD AND CARRYING WATER IN PLASTIC CONTAINERS. PHOTO CREDIT: MARTINE PERRET/UNMIT

Two prominent foodborne trematode illnesses, Opisthorchis viverrini, (O.v.) and Schistosomiasis are serious health threats, particularly in Southeast Asia, including southern China, and eastern Africa. Individuals become infected by O.v. by consuming raw fish, while for Schistosomiasis, people are infected by coming in contact with contaminated water. For both illnesses, local water resources become contaminated due to poor waste treatment facilities, so the feces from infected individuals is reintroduced into their water systems. Therefore, communities lacking infrastructure are at a higher risk of infection. Treatment for both illnesses involves a drug called Praziquantel; however, people can still become reinfected after treatment, and cost and access to the drug can be a challenge for impoverished communities.

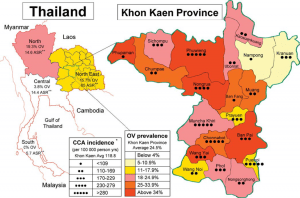

While symptoms of O. v. and Schistosomiasis are mild with slight abdominal pain, discomfort, and diarrhea, for O.v., it can become more complicated. The International Agency for Research on Cancer, IARC, classifies O. v. as a Group 1 Carcinogen because of the strong correlation between prolonged exposure to O. v. and incidence of cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), or cancer of bile ducts which drain bile from the liver into the small intestine. CCA is responsible for 19 percent of liver cancers in the United States, compared with 71% in the Province of Khon Kaen, Thailand, where prevalence of O.v. can reach up to 71%, representing the highest incidence of CCA in the world.

The World Health Organization has both illnesses on the list of Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD), so there has been an increase in investments to fund research for better treatment and prevention.

Photo Credit (left): National Institute of Health

Specifically, the Schistosomiasis Vaccine Initiative is a collaboration between the Sabine Vaccine Institute, George Washington University, the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, the Chinese Institute of Parasitic Diseases, the Queensland Institute of Medical Research, and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and aims to develop a vaccine for Schistosomiasis. In January 2015, Phase 1 clinical trials began for the Sm-TSP-2 Schistosomiasis vaccine, so what was only hope for systematic prevention is becoming a reality.

In an economic context, finding solutions for NTDs are smart investments. The World Health Organization suggests that if we can achieve the 2020 targets for the 10 most debilitating NTDs, healthier citizens would generate an estimated US$623 billion in increased productivity between 2015 and 2030.

However, climate change may be undermining efforts to mitigate the prevalence of these diseases. Ample evidence suggests that climate change could have a significant impact on the spread of both diseases by changing rainfall patterns and intensity, consequently providing better environments for both O.v. and Schisto.

The latest report (AR5) from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) states that climate change may increase drought and rainfall intensity. This means there could be fewer rainy days, but more extreme weather events, so the hard-dry surfaces create a pooling effect when it rains because the water has nowhere to go. This may increase flooding in the region while also mixing contaminated water and redistributing it to previously uninfected areas. In addition, flooding may stress already weak waste treatment facilities, which would only further contaminate water supplies (SDG 6.2).

This highlights a recurring issue for sustainable development projects: because of climate change, initiatives for education and training may not be enough. What is needed is to directly address the lack of adequate infrastructure as it is increasingly challenged by climate change.

Cultural issues add another layer of difficulty to O.v. Various media reports and prevention initiatives have suggested that ceasing the consumption of raw fish is the perfect simple solution for the problem.

However, this fails to capture the whole story, and highlights a top-down mentality that doesn’t translate well for sustainable development. The Isaan people of Northeastern Thailand are an ethnic minority and have had a tumultuous relationship with the Thai government for decades. Food is an important part of any culture, and for the Isaan people this food is raw fish, specifically a dish called Koi Pla. Consequently, the Thai government instructing the Isaan people to cease eating Koi Pla would only further alienate this minority group. This compounds the issue of O.v., but a clear focus on inclusive bottom-up workshops and educational seminars may help get the message across in a more nonthreatening way.

Public health issues are global, percolating into all cultures and compounded by climate change. This highlights the need for a collaborative interdisciplinary approach.

Fortunately, many of these environmental health issues are covered in the new 17 Sustainable Development Goals adopted by the United Nations General Assembly this past September. The call for a healthy, sustainable, and equal world has never been clearer, but these goals are a framework of organizing and mobilizing efforts on the ground in both developed and developing economies that are inclusive and bottom-up. This strategy builds off of the success of poverty reduction from the MDGs, the successor to the SDGs. To empower and mobilize people to innovate and enact change, we have to first get them healthy.

Water and Conflict: Syria

The Syrian conflict has unfortunately become one of the most horrific humanitarian crises of the past few years. Countless lives have been lost in the crisis, and the consequent influx of refugees into Europe has causes very public identity crises for many European nations facing a more heterogeneous communities and national identities. However, the journey to Europe in search of opportunity and an end to the calamity, has also taken many lives. We’ve seen the now infamous photo of the body of the Syrian child child on the Turkish shore, unfortunately not unique by any means.

Although complicated by numerous drivers, evidence suggests that the civil unrest in Syria that started in 2011 against President Bashar al-Assad was heavily influenced by severe drought between 2007-2010, the worst in instrumental record, that was likely due to climate change. Climate models in a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests that the Syrian drought was three times more likely due to human-induced climate change than natural variability in the climate.

IN THE PHOTO: A FARM IN SYRIA. PHOTO CREDIT: FLICKR/JOEL BOMBARDIER

As a result of the drought, there was a migration of 1.5 million people from rural areas to urban centers. Ill-informed agricultural and water-use policies contributed to the massive crop failures which exacerbated this migration. The issue has since escalated to a more complex conflict with an estimated 200,000 deaths, the rise of the ISIS, and the growing number of already 6 million internally displaced Syrians and over 4.5 million refugees outside of Syria.

For a full mindmap containing additional related articles and photos, visit #SDGStories

In addition to the complex scene laid out by climate change, there is a difficult history of water issues for Syria, Turkey, and Iraq, due to competing interests in the Tigris-Euphrates river basin. Turkey, lying upstream nearer the source of the rivers, is moving forward with their controversial Southeastern Anatolia Project (GAP) development plan, which includes the construction of an additional 22 dams along the rivers that are estimated to reduce flow in Syria by 40 percent and Iraq by 80 percent. As a result, it remains unclear how the interaction of these factors will play out over the next 15 years, but the situation points towards continued drought and water insecurity. It is however clear that with respect to areas of conflict, peace must first be negotiated before solutions to water issues are found.

From Mitigation to Adaptation

Water availability faces multiple threats from human induced climate change in addition to changes in land-use and land-cover. Additionally, numerous barriers to building adequate sanitation infrastructure perpetuate public health problems in some of the world’s poorest and most at risk communities. Solving the problems is no easy task; however, advances in technology may help develop solution that can be applied at appropriate scales to address the needs of these communities.

IN THE PHOTO: WATER SUPPLY BY MILITARY IN OLD DHAKA: 1.8 BILLION PEOPLE WHO HAVE ACCESS TO A WATER SOURCE WITHIN 1 KM, BUT NOT IN THEIR HOUSE OR YARD, CONSUME AROUND 20 LITERS PER DAY. PHOTO CREDIT: UN PHOTO KIBAE PARK/SIPA PRESS

Forests play an important role in regulating water quantity and quality and are therefore essential for safeguarding water resources with respect to climate and global change. However, previous forest management initiatives such as UN REDD, the United Nations Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation, have placed the focus on carbon when it comes to reforestation and management.

Thus, the goal has largely been on climate change mitigation. Although an important cause, an emphasis on forests providing multiple services, instead of solely carbon sequestration, may better address the needs of both local communities and concerns related to climate change.

As a result, this would shift the focus from solely mitigation to also incorporate adaptation goals. With the degree to which forests govern water related services at the watershed scale unclear, it is important to recognize forests as more than just carbon stores. Acknowledging the water-related services forests provide would leave communities better positioned for a future that remains uncertain. Financing development plans should therefore address adaptation goals. However, this requires detailed monitoring and data collection to ensure that the adaptation strategies being implemented are relevant for the region in question.

Sinking or Swimming for SDG 6

As of now, we appear to be treading water when it comes to SDG 6. Whether or not we as a global community with sink or swim remains largely unclear. However, it appears that we may have the tools needed to swim. As all of the SDGs, SDG 6 is deeply interconnected into the success of the 2030 Agenda. Managing water resources sustainably given the large degree of future uncertainty in the climate system is extraordinarily complex; however, we cannot afford to sit idle oscillating back and forth between varying degrees on indecision. Instead, we need decisive action on SDG 6.

Sinking is not an option.

Recommended reading: “ASIA PACIFIC SHOWS PROGRESS IN WATER SECURITY, BUT CHALLENGES REMAIN”

_ _