Lake Mead — the largest reservoir in the Colorado River Basin — is losing water at record speeds, dropping below 1,050 feet elevation for the first time ever just a few weeks ago.

The lake provides four states and millions of citizens in the west with water that Americans depend on for both agricultural and basic water necessities. Now, instead of plentiful water for the millions who are reliant on the river basin, washing up on the lake’s shores are previously submerged boats and cars.

The cause of shrinking water levels is both complex and simple at the same time: climate change and the latest most innovative technologies that stem from it — hydropower.

What is happening at Lake Mead now?

As of last week, the water level at Lake Mead dropped to 1,049 feet (319.7 meters) above sea level, marking the first time in history the lake dropped below 1,050 feet (320 meters).

According to the latest forecast by the US Bureau of Reclamation, Lake Mead’s water level will soon plummet from 1,049 feet (319.7 meters) to around 1,037 feet (316.07 meters) by this September. Going even further into the future, by September 2023, the water level will be 26 feet lower than its current elevation and only 19% of the lake’s full capacity.

Coinciding with the plummeting water level, sunken boats and trucks that haven’t been seen in ages are reemerging as Lake Mead dries up.

https://twitter.com/jmpphotography/status/1532721149842403328

Alongside boats and cars, the muddy shoreline surrounding the lake has led to dangerous driving conditions, with some saying the mud acts as quicksand, even if it appears to be relatively stable.

Last Monday, the National Park Service (NPS) even shared several photos on Twitter that showed trucks getting stuck in the mud around the shoreline and cautioned people to drive carefully.

📢 Newly exposed shoreline is dense and difficult to navigate. As a result, vehicles, vessels and people can get stuck.

❗ If you're struggling to maneuver your car, boat or yourself along the beach, immediately head to higher ground if possible. No boat or car is worth a life. pic.twitter.com/VcR0sOGOQ6

— Lake Mead (@lakemeadnps) May 24, 2022

Lake Powell — a neighboring reservoir in the Colorado River Basin to Lake Mead and the country’s second-biggest reservoir— is also drying up at an astonishingly fast rate.

According to the NPR for Colorado, a public radio network in Denver, the latest data shows Lake Powell has dropped to 3,523 feet (1,073.81 meters) above sea level. This is the first time it has dipped below the “buffer” elevation of 3,525 (1,074.42 meters).

As a result of the shrinking water levels, the west faces a looming water and energy crisis

Lake Mead provides drinking water to 25 million people in Arizona, California, Nevada and New Mexico — with the shrinking water comes a looming water crisis that will affect much of the Western United States.

Already, water cuts have been made to cope with the decrease in water levels. In January, the Colorado RIver Basin region enacted a Tier 1 shortage, which has led to mandatory water cuts that have primarily affected agriculture.

If the water level continues to remain below 1,050 feet, a Tier 2 shortage will be implemented, which will make even more significant water cuts to the four states — Arizona will go from their current cut of 18% to 21%.

Lake Mead is already well below the predictions the Bureau made last year: It predicted the water level in August 2022 would be 1,059 feet (322.8 meters) and at most 1,057 feet (322.2 meters) but already now, in May, the water level is 10 feet below their predictions.

Lake Powell, on the other hand, faces a different crisis: an energy crisis. Lake Powell is part of the Glen Canyon Dam National Recreation Area and contains the Glen Canyon Dam, which contains hydroelectricity production.

At the dam’s power plant are eight generators. Water travels in these generators through 15-foot diameter pipes, hitting and spinning turbines and producing electricity.

Yet if the water level drops another 32 feet, these generators will stop moving, halting all hydroelectricity production at the dam that provides electricity for 5.8 million homes and businesses and supplies 40 million people with water.

Over the past several years, the dam has lost 16% of its capacity to generate power as the water levels dropped 100 feet in the previous three years.

The halting of hydropower altogether would plunge many across the west in an energy crisis and would make it essential for the federal government to find an alternative electricity outlet, most likely fossil fuels.

Alongside fueling fossil fuel production, the discontinuation of hydropower at Lake Powell would make electricity costs significantly more expensive at a time when global energy prices are at an all-time high.

According to the World Bank’s April Commodity Markets Outlet Report, global energy prices are already expected to rise 50.5% this year. Lake Powell going offline would see this number dramatically increase.

How has this happened and how can it be stopped?

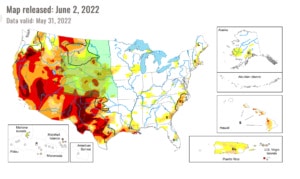

One of the biggest causes of Lake Mead’s deterioration is the increase of droughts in the Southwestern United States.

According to a study released in the journal Nature Climate Change, severe droughts have wreaked havoc on the Southwestern United States for nearly 22 years and now have become the region’s “megadrought” — a drought that has lasted two decades or longer.

Due to the high temperatures and low precipitation between the summers of 2020 and 2021, the current drought has exceeded the severity of a megadrought in the late 1500s, which the study’s authors previously identified as the driest in 1,200 years.

The study’s lead author, University of California Los Angeles geographer Park Williams, mentioned that with such dry conditions that are likely to persist, it would take multiple wet years to repair the damage.

The worst drought conditions of this year were noted in San Joaquin Valley, where the snow cover was virtually nonexistent below 8,000 feet and in turn caused the peak snow-melt water to subside much faster than normal.

This snow melt is essential in fueling nearby reservoirs in the springtime, with 30% of California’s water coming from these snow peaks.

Clearly, much damage from droughts has already been done as Lake Mead now resembles more of a kiddie pool than the once plentiful River Basin and increasing water cuts from the lake have already had an impact on agriculture.

Another factor that has led to dangerously low water levels in Lake Mead is the preservation of hydropower in Lake Powell.

Lake Powell is on the edge of an energy crisis and in trying to save the hydropower dam, the federal government is sacrificing Lake Mead.

Last month, the Interior Department made an emergency decision to buy the dam more time by releasing less water from Lake Powell to neighboring states, in order to preserve the hydropower dam (Lake Mead is one of the many water sources reliant on the water flow of Lake Powell).

The proposal called for holding back 42.6 million gallons of water in Lake Powell, which would lead to water cuts across California, Arizona, Nevada and New Mexico and result in the deterioration of Lake Mead.

As the federal government wrestles with ways to stop what seems to be an inevitable water crisis in the United States, it seems clear the US is already prioritizing energy over water access — sacrificing Lake Mead for hydropower. Yet at the same time, not saving the hydropower dam will lead to continued reliance on fossil fuel plants in the US that emit carbon emissions, fueling global warming and as a result increasing the severity and frequency of droughts.

Unfortunately, it appears whatever choice is made will be a sacrifice — hopefully one that isn’t too costly.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Glen Canyon Dam in Lake Powell in Page, Arizona on July 4, 2010. Source: Ken Lund, Flickr.