Editor’s Note: With the permission of Routledge, we are pleased to share excerpts of chapters from the book, Survival: One Health, One Planet, One Future (pub. 2019/2020). The first in the series is entitled “War and Peace” and focuses on the decline of democracy and the rise in armed conflicts. The author, George Lueddeke Ph.D., MEd, Dipl.AVES (Hon.), originally from Canada, now residing in the United Kingdom, is an education advisor in Higher, Medical and One Health education and leads the implementation of the international One Health for One Planet Education and Transdisciplinary Research initiative (1 HOPE-TD) across global regions in association with national and global organizations. Previous books by the author include Transforming Medical Education for the 21st Century: Megatrends, Priorities and Change and Global Population Health and Well-Being in the 21st Century: Toward New Paradigms, Policy and Practice.

Chapter 6: “War and Peace” from Survival: One Health, One Planet, One Future is reproduced below.

Tolstoy’s “War and Peace”

Recurring and timeless themes that thread through Leo Tolstoy’s epic, War and Peace, [1] ‘hailed as the greatest novel of all time,’ [2] depicting Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812 and its effects on Tsarist society are, among others, power, warfare, and spirituality. His existential question, “what force moves peoples?”[2] rings as true today as it did in 1869 when the novel was first published: ‘names and places have changed’ but ‘human nature remains the same.’ Moreover, as we have witnessed in the 20th century, and similarly in the beginning decades of the third millennium, power for some individual leaders can be an aphrodisiac, strengthened by appealing to events in the past and exploiting prevailing conditions. Tolstoy’s characters are no exception.

His vivid and brutal portrayal of war, like too many of today’s conflicts, is barbaric, defies human reason and remains essentially pointless — aside perhaps the realisation that the human spirit can overcome adversity and even the most brutal acts of aggression. What makes Tolstoy’s insights particularly insightful and poignant, however, according to Holmes Wilson, a co-founder and co-director of “Fight for the Future,” is how ‘an entire Russian society, unified by an outside threat, starts almost magically acting as a large meta-organism, even though there’s no obvious system of organization… when the invasion happens, it’s as if this monster just rises up out of the collective consciousness to repel the invader… ’[3]

For Wilson, Tolstoy’s writing about ‘the fading aristocracy and the Russian middle class,’ whose values were ‘pushed out to an ever-growing chunk of the planet, was considered ‘extremely relevant’ in 2015 and remains so given global events since and the rise of populism. In her article, ‘We’re repeating the mistakes that once pitched the world into disaster,’ [5] journalist Janet Daley questions whether we are ‘about to repeat the 20th century, with ideological illusions orchestrated by populist demagogues of the Left and the Right? With the most powerful countries on earth being led disastrously into conflict (or a carve-up of global influence) by men who appear oblivious to the dangers of their vainglorious strutting, she ponders, ‘How can this be happening again when we know how it ended the last time?’ [5]

The decline of democracy

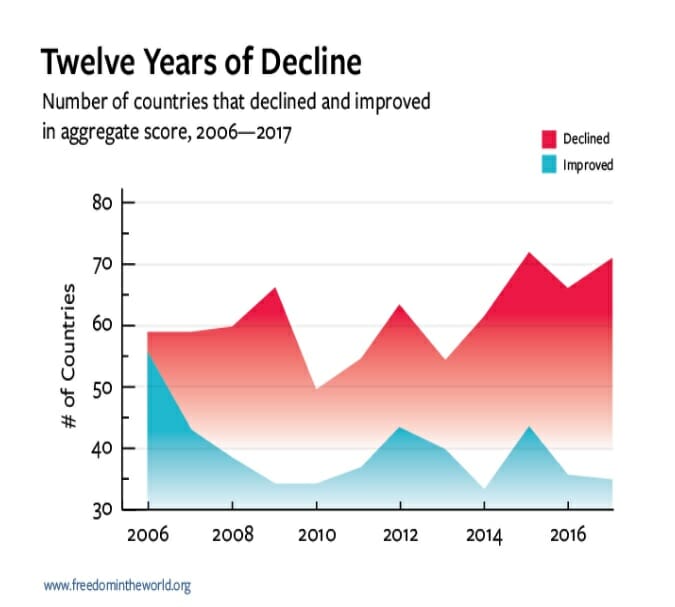

Her query and associated concerns about America’s path toward protectionism and isolationism are also germane to the future of democracy which now also finds itself in peril globally, according to Freedom House, a non-partisan Washington think tank [5]. Their annual survey findings [6], as shown in Figures 6.1 and 6.2, echoed by the European Council Foreign Relations [7], Human Rights Watch [8] and The Economist Intelligence Unit [9] confirmed that countries where democracy declined (e.g., ‘right to choose leaders in free and fair elections, freedom of the press and the rule of law) outnumbered those that gained, and that there was a drop in the percentage of free countries. Continuing down the road of protectionism, as ‘the inter-war years should have demonstrated beyond doubt,’ can lead not only to undermining economic progress, threaten democracy but also precipitate ‘all-out global conflict, as ‘the parallels with 1914 are stark.’ [5]

Adding to the vulnerability of democracy are ‘States attempting to influence public opinion to suit their aims through disinformation, propaganda, fake news and alternative facts (once known as lies)….’[10] While ‘nothing new,’ ‘the internet, social media and platforms such as WikiLeaks, Professor Rainer Gerling, IT Security Officer of the Max Planck Society, cautions that ‘the number of information providers has dramatically increased, and traditional journalistic ethics and truthfulness are often left by the wayside.’ As a result, ‘disinformation’ has become widespread, including elections and causing to question the use of computer software in processing voter information, which must be kept ‘secret, free and secure.’ He affirms that, unlike the US, ‘there will be no online political elections for the foreseeable future. ‘Ultimately,’ he posits ‘each citizen must decide for themselves what they believe and what they don’t’ and ‘Only one thing can help here: education.’ [10]

The decline in global democracy may be attributable to a combination of factors: a shift in American foreign policy – military and economic – from global leadership to national priorities, continuing inequalities and economic hardships and the weakening of global structures in place to protect civil society. Noting that ‘the tectonic plates of world power are shifting,’ Michael Burleigh, author and historian, points out that ‘America, the guarantor of Western wealth and stability, is being steadily supplanted by a more assertive China.’ [11] Recognising this uncertainty, some countries may decide to accelerate their own national agendas – Turkey, Russia, Hungary, Bahrain and Venezuela, as examples. Besides, some of these countries – Malaysia, New Zealand and several of the poorer countries of southern Europe ‘are already in China’s pocket.’[11] Many hope to gain from China’s ‘$1 trillion One Belt, One Road master plan, which is already funding rail and sea links that will eventually connect Europe with China’s rich industrial heartlands.’ Summarising the state of political manoeuvring across the globe, Burleigh points to ‘assertive Russia (which) is acting like a universal spoiler,’ the continuing global anxiety of the US threatening ‘war with North Korea or Iran’ – all taking place at a time when ‘The rise of intelligence threatens to make the world more mystifying’ [12] and likely more dangerous.

The “big” picture: a more peaceful world?

In Sapiens [13] Yuval Harari comments that ‘Most people don’t appreciate just how peaceful an era we live in’ comparing our lives a thousand years ago and mass statistics in 2000, when ‘wars caused the deaths of 310,000 individuals and violent crime killed another 520,000. And, while devastating for families, ‘from a macro perspective,’ he says, that, ‘these 830,000 victims comprised only 1.5 percent of the 56 million people who died in 2000.’ Going back to 1400 global deaths peaked in the 17th and 20th centuries with between 3,000,000 –11,500,000 dying during the Thirty Years War (1618 and 1648) and close to an unimaginable 100 million – military and civilian – in the First and Second World Wars.[14]

Armed conflicts: “perpetual global situations”?

As indicated on the graph, other major conflicts involving the US have been the Korean War (1950-1953) and the Viet Nam War (1955-75) with estimated deaths at around 47,000 and 34,000, respectively. Beginning what is arguably known as the War on Terror, ‘the US-led war in Afghanistan was a response to the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on America – with total loss of life nearly 3000 – in which Coalition forces toppled the ruling Taliban in 2001.’ In his article “Mapping a World From Hell,” [15] Tom Engelhardt, a co-founder of the American Empire Project [17], ‘presents a unique map (Figure 6.4) that shows ‘an increasingly complex set of intertwined conflicts…stretching ‘from The Philippines through South Asia, Central Asia, the Middle East, North Africa and deep into West Africa…’

Figure 6.3: War on terror (2015-2017)

‘Almost 17 years ago, there was one. Now the count is 76 and rising. Meanwhile, great cities have been turned into rubble. Tens of millions of human beings have been displaced from their homes. Refugees by the millions continue to cross borders, unsettling ever more lands. Terror groups have become brand names across significant parts of the planet. Our American world continues to militarize.’[16]

Impact on society has generally been disbelief. The 2015 International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War study [15] concluded that ‘Total deaths from Western interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan since the 1990s are much more and likely constitute around 4 million (2 million in Iraq from 1991-2003, plus 2 million from the “war on terror”) and could be as high as 6-8 million people when accounting for higher avoidable death estimates in Afghanistan.’[15] In addition, despite 54 nations and rebel and terror groups fighting ISIS (the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) across the Middle East and Africa, the damage inflicted by the now weakened organisation is incalculable and remains to this day with a growing presence in Afghanistan.

While the Iraq death toll reaches an unforgiveable 500,000 since the start of the US-led invasion in 2003 and Syria comes close at about 465,000 killed in six years of fighting, creating ‘a dire humanitarian crisis’ displacing 6.1 million internally with another 4.8 million seeking refuge abroad, Afghanistan remains unique in terms of fatalities and endless conflicts without long-term resolution.[19]

The United States first invaded Afghanistan on October 7, 2001, as part of Operation Enduring Freedom. According to estimates in a new report released by Costs of War, ‘war has directly resulted in the deaths of 149,000 people in Afghanistan and Pakistan between 2001 and 2014. Previously, the Soviet war that began in December 1979, and lasted until February 1989 killed about 15,000 Soviet soldiers and about two million Afghan civilians. In ‘by far the longest war the nation has fought,’ the US lost about 2,500 soldiers and coalition forces about 1,000 from 2001-2017 – ‘By comparison, 4,523 U.S. troops have been killed since the Iraq war began in 2003.’ [20,21] ‘Now 2017,’ the CNN reports, ‘with fewer than 10,000 US troops left in Afghanistan, mostly working as trainers, the war continues to drag on into its 16th consecutive year, with no end in sight.’ [22]

Perhaps, as mentioned, nowhere in the world is the breakdown of the world order felt more than in Afghanistan – a multi-ethnic and mostly tribal society of around 36 million people – demonstrating the depravity, senselessness of these endless conflicts without long-term resolution.

War correspondent Anthony Loyd, who has regularly returned to the country over 21 years, in an article ‘The War That Never Dies’ [23] presented a detailed and gruesome account about life in the nation today, the role being played by Afghan soldiers, police, the US, UK, Russia, the Taliban, and Isis – which given its barbarity ‘has caused a paradigm shift in the allegiances of regional actors on the war, dramatically altering the constellation of enemies and allies in this latest era of the Great Game.’ Without ‘huge foreign financial and military support,’ he says, there is every reason to believe that ‘the whole edifice will collapse into the same paroxysm of violence that had followed the overthrow of the communists in 1992…catapulting Afghanistan backward into even greater levels of violence.’

An aspect about the conflict in Afghanistan – that may resonate with similar conflicts elsewhere and that could have implications for Syria, Iraq, Yemen, to name several volatile regions – is the reason a senior Taliban official gave why so many young men became involved with suicide bombings and volunteer for suicide missions. While recognising that ‘these boys’ ‘had a right to life as you and I do’, he also acknowledged that ‘they also had a right to revenge’ since ‘They had lost someone.’ For the correspondent, one of the fundamental Afghan lessons is that ‘the investment of war in a rentier state accrues violence rather than diminishes it.’

‘There is no other work, and we need the money for food,”

a frail 14-year-old graverobber told me.’[23]

Global military spending

A report by the US Watson Institute at Boston University on the total US budgetary costs of war from 2001 through the fiscal year 2018 reveals that ‘$5.6 trillion were spent on wars in Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan and Pakistan, and Post-9/11 Veterans Care and Homeland Security24 (Table 6.1).

Table 6.1

As shown in Figure 6.5 [25], in 2016 US military expenditures were by far the largest share of the global total at 36% was $611 billion – over three times the amount spent by second-placed China. Russia increased its military expenditures by 5.9 percent to $69.2 billion. Western Europe in turn increased defense spending by 2.4%.

Figure 6.4

At the 70th session of the General Assembly in 2015 and the adoption of the 2030 Agenda, including the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, the SDGs, then Secretary-General Ban ki-moon posed an important existential question: “Why is it easier to find the money to destroy people and planet than it is to protect them?”[26]

A similar refrain has been heard from the World Economic Forum (WEF). Referencing the 2016 Global Peace Index report28 the WEF concluded ‘that 2015 was a bad year for international peace and security,’ recording ‘a further deterioration in global peace based on historic trends,’ and witnessing ‘the highest number of global battle deaths for 25 years, persistently high levels of terrorism, and the highest number of refugees and displaced people since World War II.’

The Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), ‘a think tank dedicated to developing metrics to analyze peace and to quantify its economic value,’ in its report [28] highlighted that the economic impact of violence to the global economy was $13.6 trillion (or 13.3% of world GDP) in 2015 in terms of purchasing power parity (PPP), ‘considered conservative as there are many items that have not been counted in the study due to the lack of available data.’ This is equivalent to $1,876 PPP per annum, per person or $5 per day for every person on the planet, or 11 times the size of global foreign direct investment (FDI).’

In contrast, the amount spent on ‘peace-building – the activities that aim to create peace in the long term – totaled $6.8 billion or only 0.9% of the economic losses from conflict! [28] …..

References

(1) Tolstoy L. (trans. Ann Dunnigan). War and Peace. London: Penguin Books Ltd.; 1968.

(2) The Quarterly Conversation War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy (Review) (accessed 14 July 2015).

(3) Sorcinelli G. Holmes Wilson and the Timeless Themes of “War and Peace” by Leo Tolstoy (accessed 20 August 2016).

(4) Daley J. We’re repeating the mistakes that pitched the world into disaster last century. But there’s still hope (accessed 10 August 2017).

(5) Freedom House. Champions for Freedom (accessed 15 January 2018).

(6) Abramowitz MJ. Democracy in Crisis (accessed 10 February 2018).

(7) European Council on Foreign Relations. A normative crisis: How to protect democratic values in Europe (accessed 19 January 2018).

(8) Human Rights Watch. World Report 2018 (accessed 24 February 2018).

(9) The Economist. Democracy continues its disturbing retreat (accessed 10 February 2018).

(10) Gerling RW. Cyber Attacks on Free Elections (accessed 19 November 2017).

(11) Burleigh M. There’s never been a worse moment in history for a parliament frozen in fear’, The Mail on Sunday. 5 February 2017.

(12) Ferguson N . The rise of intelligence threatens to make the world more mystifying’, The Sunday Times. 11 February 2018: 25.

(13) Harari YN. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. London: Harvill Secker (Random House); 2014.

(14) Ritholtz B. Global deaths in conflicts since 1400 (accessed 27 September 2017 ).

(15) International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War.Body Count: Casualty Figures after 10 Years of the “War on Terror” – Iraq Afghanistan Pakistan (accessed 19 October 2017).

(16) Engelhardt T. Mapping a World From Hell, (accessed 10 January 2018).

(17) Engelhardt T and Frasers S . American Empire Project – About The Project. http://americanempireproject.com/about/ (accessed 12 January 2018 ).

(18) Watson Institute (Brown University). Costs of War Project (accessed 12 January 2018)

(19) Freedman l. Can There Be Peace With Honor in Afghanistan? FP the Magazine 2017, 26 June (accessed 10 November 2017).

(20) Taylor A. 149,000 people have died in the war in Afghanistan and Pakistan since 2001, report says, Washington Post. 3 June 2015.

(21) The Associated Press. A timeline of U.S. troop levels in Afghanistan since 2001. Military Times 2016 (accessed 12 November 2016).

(22) Westcott B. Afghanistan: 16 years, thousands dead and no clear end in sight (accessed 12 November 2017).

(23) Loyd A. The War that Never Ends. The Times Magazine 2017; 11 November 2017.

(24) Crawford NC. United States Budgetary Costs of Post-9/11 Wars Through FY2018 (accessed 15 January 2018).

(25) Peter G. Peterson Foundation. The United States U spends more on defense than the other eight nations combined (accessed 16 January 2018 ).

(26) Interpress Service (IPS). Why is it Easier to Find Money to Destroy People than Protect Them?’ Asks U.N. Chief (accessed 17 November 2016).

(27) World Economic Forum. War costs us $13.6 trillion. So why do we spend so little on peace? (accessed 10 June 2016).

(28) Institute for Economics and Peace. Global Peace Index 2016 (accessed 19 November 2018).

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — Images: All diagrams are in the original published by Routledge; other visuals (photos, videos) are added by Impakter. In the Featured Photo: Soldiers Open Fire in Support of Troops During Operation Chakush in Afghanistan in 2007 Source: Flickr Photographer Cpl Jon Bevan Image 45153219.jpg