In September 2018, the United States decided to suspend $300 million in aid assistance to Pakistan in light of what the U.S. saw as the country’s failure to combat terrorist groups. This decision was based on the claim that the war on terror in Afghanistan has gone on for 18 years too long, and Pakistan must do more given the country’s tactical border position and its history of militant groups residing in North Waziristan. The $300 million had been designated from the Coalition Support Fund (CSF) and was reassigned just before the funds were set to expire on September 30 last year.

The primary goal of the CSF is to reimburse U.S. partners for their provision of logistical, intelligence, and military support to U.S. operations. It is important to recall that the Department of Defence’s Appropriations Act of 2018 stated that Pakistan would not qualify for reimbursement for its military assistance unless the nation complied with the U.S. in its 12 counterterrorism efforts.

When the South Asia Strategy was introduced in August 2017 it acknowledged Pakistan’s alliance and the sacrifices of its people, but also suggested that the nation must maintain stronger efforts to combat the numerous terrorist groups active in both Pakistan and Afghanistan. The decision to suspend aid to Pakistan was made on the basis that the country had failed to commit to its partnership with the U.S. and to removing terrorist groups that have continued to use north-western Pakistan as a safe haven to flee from U.S. forces in Afghanistan.

Pakistan’s decision to refrain from military operations against the Haqqani network — a North Waziristan based insurgent group with close ties to Al-Qaeda and other terrorist groups (Lashkar-e-Taiba, Tehrik-e Taliban, and Harakat-ul-Mujahideen to name a few) — has been a significant point of contention. While Pakistan sees the group as an ally and source of intelligence, the U.S. views Pakistan as the devised strategy’s weakest link due to this approach.

The South Asia Strategy also proposed a strengthened partnership between India and the U.S. in order to increase economic prosperity in Afghanistan. The U.S.’s burgeoning military and business partnerships with India along with their mutual interest in China, have contributed to further tensions with Pakistan.

Pakistan’s utilization of U.S. aid has come into question on several occasions given challenges the country encounters during disbursement. Pakistan’s inability to reassure international actors and the U.S. that foreign aid does not make its way to Taliban groups raises notable concern, especially since the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) placed the country on the terror financing watchlist in 2018. In October of 2019, the FATF will make its decision on whether or not to blacklist Pakistan for activities indicative of continued terrorism financing.

While the U.S. was one of Pakistan’s first allies after the latter’s independence in 1947, their political relationship has been a tumultuous one.

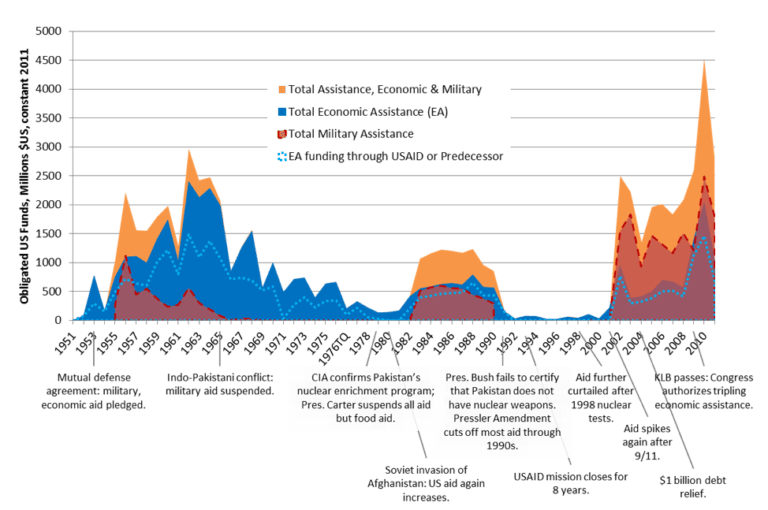

It is worth noting that anti-American sentiments in Pakistan have little to do with the current administration in either country. The two have inherited extremely fragile hostilities and security threats over decades of inconsistent political ties. While the U.S. was one of Pakistan’s first allies after the latter’s independence in 1947, their political relationship has been a tumultuous one. In fact, the U.S. suspended military, economic, and food aid to Pakistan as early as 1965 and through most of the 1990s (see Table 1).

Indeed, Pakistan became an important player in the aftermath of 9/11 when it opened its airspace to the U.S. and shared intelligence on militant activity. Nevertheless the relationship between the two allies remains weak. While the Trump administration has publicly held Pakistan responsible for harboring the Taliban and other groups, this is not an isolated incident of blame. Several years earlier, the Bush administration reportedly gave Pakistan an ultimatum — comply in the fight against Al-Qaeda or face the consequences of a more aggressive approach by U.S. forces within the nation.

Additionally, it was during the Obama administration in 2011 that Osama bin Laden, the Taliban leader who claimed responsibility for the 9/11 attacks, was killed in a raid in Abbottabad, Pakistan on May 2nd. The U.S. kept this operation a secret from Pakistani authorities until they carried it out. After the operation, the U.S. suspended $800 million in military aid to Pakistan, reflecting its continued frustrations with the country.

Tensions have continued over the arrest of Dr. Shakil Afridi by Pakistani authorities shortly after Osama bin Laden’s death. Afridi had led a fake vaccination campaign in Abbottabad which aided the CIA in confirming Bin Laden’s whereabouts. With multiple charges of anti-state actions, Pakistani courts have been reviewing Afridi’s petition since 2014. His original sentence was 33-years (later reduced to 23).

While Pakistan seemingly holds Afridi hostage pending negotiations with the U.S., it is pertinent to note that Pakistan has been demanding the release of Dr. Aafia Siddiqui for several years. Siddiqui is a Pakistani neuroscientist who disappeared for five years and resurfaced in Ghazni, Afghanistan in 2008. She was arrested for the attempted murder of two U.S. soldiers and has been in U.S. custody ever since, serving an 86-year sentence. Dubbed Lady Al-Qaeda, the narrative around her life before and during her disappearance varies from militant support activities, to Pakistan’s intelligence agency picking her up, to Pakistan and the U.S. holding her captive at various points in time. Her release is fervently fought for by social activists in Pakistan as well as ISIS who has demanded an exchange for captives of its own.

In December 2018, in response to the accusation that Pakistan knowingly harbored Bin Laden, Foreign Secretary Tahmina Janjua stated that such accusations could seriously impact Pakistan’s support in Afghanistan and impede vital cooperation moving forward. Prime Minister Imran Khan countered President Trump’s public statements of the nation’s neglect of militants, citing the 75,000 Pakistani lives lost in addition to an economic loss of $123 billion fighting the U.S.’s war on terror. He maintained that no amount of aid provided or suspended would ever make up for Pakistan’s sacrifices.

Pakistan is resolute in its stance that it has played a key role in the fight against terrorism and that the U.S. will realize as much over time. In fact, Pakistan has taken several strategic actions prior to Prime Minister Imran Khan’s meeting with President Trump on July 22nd.

In June 2019, Khan vowed to take a more aggressive stance on militant groups with bases in Pakistan. On July 17, authorities re-arrested militant group leader Hafiz Saeed, the same man purportedly responsible for plotting the 2008 Mumbai terror attacks and labelled a designated global terrorist by the U.S. According to new charges, he used his charitable organization, Jamat-ud-Dawa, as a front to support militant groups with donations. Indian Ministry of External Affairs spokesperson Raveesh Kumar heavily criticized the arrest stating that Pakistan has arrested militant leaders and followers in the past only to allow them to walk free soon after. This includes Saeed who was put under house arrest in early 2017 and released later that same year.

Local community sentiment in Pakistan is deeply affected by the weight of such accusations under the international spotlight. While some engage in intelligent debate citing historical and current facts, others participate in defensive and hostile arguments which further fuel fear and misunderstanding. The more extreme groups take to the streets of major Pakistani cities and hold anti-U.S. protests.

As it stands, opposing U.S. and Pakistani narratives desperately need transparent communication rather than Twitter feuds and roadside protests.

When PM Imran Khan visited the White House on July 22nd, the surprisingly cordial and almost friendly banter between the two leaders was a far cry from the Twitter sparring the two have previously engaged in. Both PM Khan and President Trump recognized that they are in a capricious yet optimistic position in terms of peacebuilding efforts in Afghanistan, and negotiations with the Taliban are the most productive they have ever been. President Trump acknowledged that Pakistan has been extremely helpful and cooperative in recent efforts made. He also expressed anticipation to repair their alliance with the possibility of resuming aid and/or lifting sanctions (on some level) in the future.

During PM Khan’s interview with FOX news anchor Bret Baier, when asked about the likelihood of Dr. Afridi’s release, Khan responded that in Pakistan the former physician is considered a spy loyal to the U.S. He added that tensions remain around the lack of Pakistani involvement in the operation that led to Osama bin Laden’s death. Khan clarified that it was originally the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) Agency’s intel that led to locating bin Laden in the first place. In short, the operation continues to be a source of embarrassment for Pakistan and has resulted in feelings of betrayal between the two allies.

To answer Baeir’s question, the release itself is a difficult decision to make, even for a man in Khan’s position, due to strong opposition. Khan did however cite the possibility of negotiations over time, vaguely indicating a potential future prison swap of Shakil Afridi and Aafia Sidddiqui. Khan shared that he and his team appreciated President Trump’s straightforwardness on all issues addressed during their closed White House meeting. He clarified that the purpose of this meeting was not to address the recovery of financial assistance, but rather bring both leaders on the same page to resolve a persistent history of mistrust and hostility.

Editor’s Picks — Related Articles:

“Transboundary Rivers of South Asia – The Case for Regional Water Management”

“Global food systems and Aid for Trade: a good mix for financing the SDGs”

“Global food systems and Aid for Trade: a good mix for financing the SDGs”

With Baier, Khan also discussed the India-Pakistan conflict, specifically the need for U.S. intervention over issues including Kashmir.

The Kashmir Question

Khan highlighted his agreeable stance on U.S. mediation, paralleling President Trump’s press conference statement that India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi had made the same request. Khan went on to claim that Pakistan would willingly give up its nuclear weapons if India does the same because a nuclear war between the two would be an act of self-destruction. After his visit, Khan continued to reiterate his agreement with President Trump that the U.S. can play a pivotal role in conflict resolution between India and Pakistan.

It is interesting to note that while the Indian Ministry of External Affairs quickly retaliated that no such mediation request was made, Modi’s usually active Twitter account failed to acknowledge or reject as much himself. Indeed, according to the 1972 Simla Agreement and the 1999 Lahore Declaration, bi-lateral meetings are the designated mode to resolve issues between India and Pakistan, particularly over the disputed territory of Jammu and Kashmir. Perhaps after over 50 years of persistent political tensions, parties both directly and indirectly impacted by the India-Pakistan conflict are asking, “is there a better way?”

Unfortunately such presumptions were short lived, and the political climate between India and Pakistan recently escalated. On August 5th PM Modi’s nationalist government passed a legislation that stripped India-occupied Kashmir of its statehood, effectively scrapping the provisions (Articles 370 and 35-A of India’s Constitution) that have granted Jammu and Kashmir the autonomy to pass its own laws since 1949. The bill also proposed that the territory be split into two separate union states.

Kashmir has been under complete lockdown since then, with hundreds arrested and injured amid violent protests, and many pilgrims and tourists hastily evacuated. The situation continues to worsen with many civilians prisoners in their own homes with limited transport, food, and other resources.

The legislation has taken the rest of the world by surprise, particularly China and an infuriated Pakistan.

In his public address on August 9th, Modi stated that this move will mark the end of terrorism that was allowed to grow in power and presence because of Pakistan’s support of militant activity within Jammu and Kashmir.

Thousands of Pakistanis have taken to the streets in protest and government officials, including Khan, are condemning the human rights violations taking place before the rest of the world. Fear of genocide to turn the Muslim-majority region into a Hindu-majority one has made the possibility of war a very real and imminent threat.

What was mutual hope for a reset of Pakistan and the U.S.’s relationship leading to a genuine alliance, has become a situation in which PM Khan is urging President Trump that this is the time to mediate.

Will Khan make good on his promise of Pakistan doing its part in peacebuilding efforts in Afghanistan? Will Pakistan walk away from peace negotiations with the Taliban in protest over what it dubs as the U.S.’s silence over Kashmir’s loss of autonomy? Given decades of complex history and the current state of affairs, the next step is difficult to predict.