It’s become conventional wisdom that technological progress destroys jobs but also creates new ones balancing out the loss after a painful period of adjustment. Painful for those out of a job who are too old or unable to learn new skills. It’s also conventional wisdom that with the tech revolution unleashed by Silicon Valley, this time will be different. That the jobs destroyed by Artificial Intelligence (AI), by computers and robots, will never be replaced. Tech entrepreneurs, like Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg and Sam Altman in the lead, and a growing number of politicians and social scientists, are however confident that they have a solution: Universal Basic Income (UBI).

Is UBI really a solution? And how serious is the disruption caused by automation of tasks and are most jobs left for humans only the low-paid ones in personal services? Is there another, better solution?

Here, I will argue that the disruption is not likely to be as devastating as predicted in most current studies with scary titles like “How The Robots Will Take Away Your Jobs and Kill The Economy”. And in any case, there’s another, better solution than UBI: Supplementary income to top up the difference and make non-automated jobs pay better. Call it: Utility-Added Income (UAI) – because it would recognize the utility (the value, the usefulness) to the whole community of jobs that are undervalued by the market in an AI-filled world, like personal services, nurses, care-givers, teachers.

So, in an AI-filled world, are we facing a devastating disruption in the job market, with permanent unemployment for the majority of humans? To be fair, not all tech titans and artificial intelligence experts think a tech Armageddon is around the corner.

One famous scientist, Fai Ku Lee, thinks otherwise. He developed the world’s first speaker-independent, continuous speech recognition system as his Ph.D thesis at Carnegie Mellon. This is a man worth listening to, he knows what he’s talking about, he once worked for Apple and Google and is now a successful Chinese venture capitalist based in Beijing, helping China become a leader in AI. He is also a best selling author and in the closing section of his latest book, AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order, he explains how creativity and compassion are the key to creating lasting and non-replacement jobs in an AI-filled future.

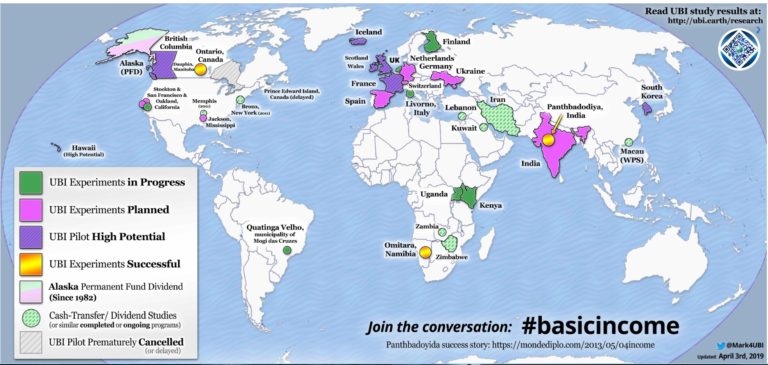

The Explosion in UBI Experiments

Fai Ku Lee’s reassuring words notwithstanding, people are in a panic. There is a plethora of UBI experiments around the world, as this map (updated to 3 April 2019) illustrates:

In the U.S., UBI research is fast becoming serious business. Four Stanford graduate researchers are currently setting up a platform to map UBI research that should come online soon in 2019. The aim, as they explain, is “to provide pertinent summaries of articles, research papers, books produced on UBI to date, highlighting important findings from each and ensuring that core areas such as health, crime, stigma, childhood poverty and gender equity are covered”.

There is even a UBI Cities Toolkit called Basic Income In Cities: A Guide to City Experiments and Pilot Projects. Launched in early November 2018 at the National League of Cities annual meeting, the toolkit highlights emerging practices and shares insights on the process of designing UBI experiments “in ways that are ethical, rigorous, informative and consequential for local and national policymaking”.

Unquestionably, even if some people like Fai Ku Lee see a silver lining in the AI revolution, most experts do not and the world is on a UBI research binge.

The most advanced experiments are in Finland and Kenya. Let’s take a look at both. Note that I’m not including here the “redditto di cittadinanza” (citizen’s income) that the populist Italian government started distributing last month because it hasn’t been set up as a UBI experiment with a control group. It’s merely political pork to fill a 5 Star Movement electoral promise. But even the best of UBI experiments have not given satisfactory results, and here’s why.

What’s Wrong with UBI Experiments

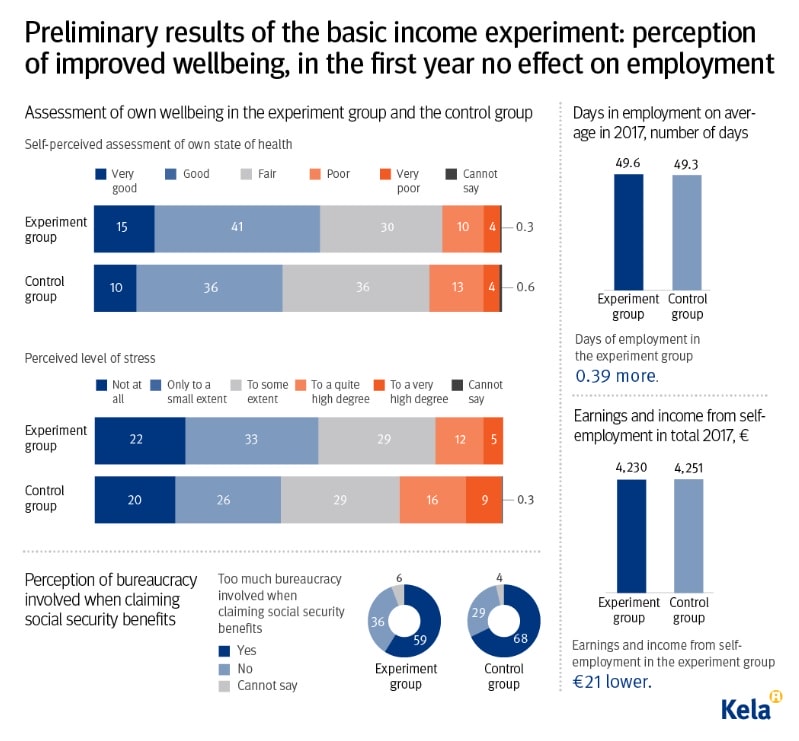

Finland’s results were disappointing. The experiment, carried out by Kela, the Social Insurance Institution of Finland, in 2017-2018 was stopped early as the government did not feel results warranted their continuation and that it would be better to explore other ways to improve social welfare.

The experiment involved a random sample of 2,000 unemployed people aged 25 to 58 who were paid a monthly stipend of €560 (£475) , with no requirement to seek or accept employment. Any recipient who took a job continued to receive the same amount. To evaluate results, a control group of similar people drawing standard unemployment benefits was set up.

This said, the experiment wasn’t a total disaster. Preliminary results were presented at Säätytalo, “House of the Estates” on Friday, 8th February 2019:

As you can see from the data, compared to the control group, there was measurable improvement in the first year on some parameters, particularly perceptions of well being and levels of stress, but no significant difference in employment results. Perhaps most worrying, is the fact that average earnings and income from self-employment in the experiment group were actually lower (€21), if not by much. As Olli Kangas, scientific leader of the study and Professor of Practice at the University of Turku, succinctly concluded:

“No significant effects on employment, but important effects on well-being.”

Looking at this from the standpoint of job disruption caused by AI, it is hard to see how an UBI-type measure can help. The reason is simple: The Finnish experiment did not have AI in mind. It was aimed at studying how it would be possible to reshape the Finnish social security system so that it better corresponds to changes in working life. The question simply was: Could a guaranteed income incentivise people to take up paid work by smoothing out gaps in the welfare system?

As we saw, there was no definitive answer. But, more importantly, the context for our purpose here is wrong. It assumes that there is actual paid work opportunities out there just ready to be taken up by the unemployed. This assumption may be correct for Finland today, but it cannot hold in a world where jobs are destroyed by AI.

This problem of the “wrong context” is likely to affect results of all presently ongoing (or planned) UBI experiments. It will inevitably bias all conclusions, leaving intact only one (self-evident) observation: That when people get more welfare money, they feel happier and less stressed.

In Kenya, the UBI experiment is still ongoing and results are far more encouraging than in Finland. Dubbed “the most important and thorough study about UBI in history”, it consists of cash transfers from NGO GiveDirectly’s $30 million fund, intended to benefit 21,000 adult Kenyans. The fund, created by four graduates of Harvard University and MIT is backed by GiveWell and Google.org.

In an interview on Impakter in 2016, Ian Bassin, COO Domestic of GiveDirectly gave a definition of what basic income is in a framework of aid to development and achieving the SDGs:

“A ‘guaranteed basic income’ or ‘basic income guarantee’ is the idea of providing a minimum floor for all members of a community. It’s enough to meet basic needs, so it would be enough to live on without work or other forms of income. It’s guaranteed over the long term so that you can make decisions about major life plans with a minimum level of basic security. And it’s universal in that everyone gets it.”

Note how the concept is linked to Maslow’s basic needs, a classic pillar of development aid. The idea is simple: Remove the shackles of poverty, trust the people to know best what they need, give them cash and thus the freedom to decide for themselves.

GiveDirectly is certainly part of “changing the debate on giving cash to the poor”. The fact that it relies on “rigorous experimental research (randomized controlled trials) to measure impact is a plus. The fact that GiveDirectly uses researchers that are “fully independent and independently-funded” (as announced on its website) adds to the credibility of evaluations of its work. Two major studies are currently in progress. One is designed to answer the question: What are the macroeconomic and long-term impacts? The other: What transfer timing and information are most effective for recipients?

Now, after some five years of operation, results of the Kenya experiment are becoming visible. Foreign experts who have visited the villages where  GiveDirectly is active have returned with glowing reports. For example, this one from Brazilian UBI expert Eduardo Matarazzo Suplicy, author of Brazilian Law 10.835 / 2004 which establishes the implementation, in stages, of a UBI for all people in Brazil. Of all the positive results he witnessed, Suplicy noted that “most remarkable was the redefinition of gender roles. Because women also receive the benefit, we hear from them how they feel freer in deciding where to spend their money.”

GiveDirectly is active have returned with glowing reports. For example, this one from Brazilian UBI expert Eduardo Matarazzo Suplicy, author of Brazilian Law 10.835 / 2004 which establishes the implementation, in stages, of a UBI for all people in Brazil. Of all the positive results he witnessed, Suplicy noted that “most remarkable was the redefinition of gender roles. Because women also receive the benefit, we hear from them how they feel freer in deciding where to spend their money.”

Several factors have facilitated GiveDirectly’s action and helped to turn it into the world’s main organization that administers “unconditional cash transfers”.

First, consider that by 2015, the ground was prepared to move from “conditional cash transfer” to “unconditional cash transfer” such as GiveDirectly does. Since the early 2000s, governments around the world had started experimenting with providing poor people with cash grants under conditions, for example that they follow through on a commitment like sending their children to school. Early success and the relative affordability of these conditional cash transfer programs made them popular and many began asking if the “conditions” were needed.

A groundbreaking study published in 2016 showed they were not. Carried out in Rarieda, Kenya, between 2011 and 2013 by two Princeton University experts Johannes Haushofer and Jeremy Shapiro, it used early GiveDirectly data with support from Innovations for Poverty Action to measure the data and funding from the National Institutes of Health.

The study showed, in the words of its authors, “significant impacts on economic outcomes and psychological well being” (see results of the randomized control trial).

Another element that facilitated GiveDirectly‘s experiment is the presence of M-Pesa, a mobile money service created in 2007 by Safaricom, a Vodafone telephone company in Kenya. It is widely used by Kenyans, including in rural areas. M-Pesa users simply rely on their cell phone and do not need a bank account; as a result, their financial transactions such as deposits, transfers, and savings are safe, fast and cheap.

As GiveDirectly likes to point out, cash transfers “have arguably the strongest existing evidence base among anti-poverty tools, with dozens of high-quality evaluations of cash transfer programs spanning Africa.”

There is no question that this is all good and well to tackle poverty now. But the problem to adapt this solution in a future AI-filled world is evident: Cash transfers (which can be thought of as an early form of supplementary income) are in fact an “anti-poverty tool” that works in Africa today, i.e. in the non-AI-filled world of developing countries. There are still plenty of low-skill jobs and tasks around that become within reach with the nudge of a cash transfer.

In an AI-filled world, such jobs no longer exist.

The Solution to the Labor Market Disruption Caused by AI: UAI

In principle, UBI is a logical solution: Once the jobs most people hold have disappeared, give them a basic income at a level such that they are kept out of poverty (basic needs are met) and can enjoy a dignified life. Tax the tech titans that have caused the labor market disruption to pay for UBI.

Tech titans are likely to agree to be taxed: After all, in a world where 99 percent of humanity is jobless and impoverished, there will be no market for tech goods. It is the same reasoning that visionary Henry Ford employed when he produced his Model T and said:

“I will build a new car for the great multitude, constructed of the best materials, by the best men to be hired, after the simplest designs that modern engineering can device; so low in price that no man making a good salary will be unable to own one, and enjoy with his family the blessing of hours of pleasure.”

The key words here are: “so low in price that no man making a good salary will be unable to own one”. In other words, there needs to be a balance between the cost of goods and the disposable salary of customers – or the goods won’t get sold. Ask Amazon’s Bezos or Alibaba’s Jack Ma: If prices are out of reach, people won’t buy.

In that respect, the AI-filled world won’t be any different from Ford’s world.

Yet the UBI scenario is still wrong on two counts:

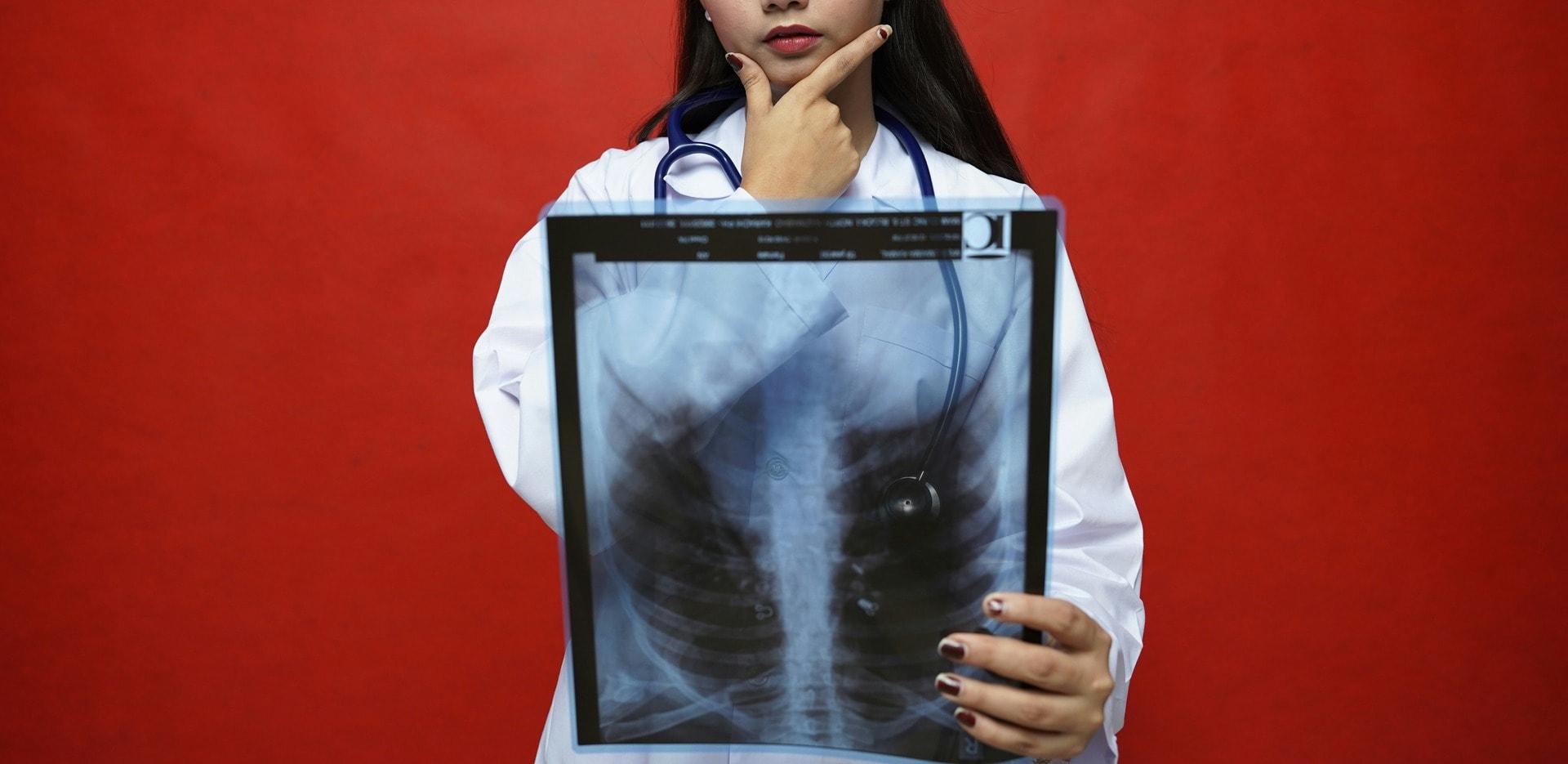

- UBI might save the market for tech titans, but it will not restore dignity to the people: To have a minimum income but no job won’t cut it; as Freud remarked, “Love and work are the cornerstones of our humanness”; without work, any work, people lose their identity, they suffer stress, in one word, they are unhappy. A recent Pew Research survey of over 4,000 adult Americans confirms that people find “life satisfaction in four areas”: friends, career, romantic partner or spouse and good health; in short, UBI is not the same as a good career;

- UBI does nothing to address the growing imbalance in salaries in personal services, particularly in the health and education sector compared to business management or entertainment.

Addressing that imbalance is what will save our future “careers” and ensure that the economy is not thrown out of balance by the onrush of automated jobs.

We all agree that nurses, caregivers, caretakers for the elderly or primary school teachers are woefully underpaid – even now, before the full onslaught of the AI disruption. That’s where a policy of providing a supplementary income to top up the difference makes more sense than UBI. I propose we call it UAI – Utility-added Income, to indicate that portion of income needed to reflect the job’s full utility (or usefulness) to the community at large.

Note that UAI is not the same thing as a minimum wage: UAI does not put a floor under wages, it “pumps” them up by adding cash – in that sense it’s like a cash transfer. Also, rather than settling on a fixed sum, the added cash could be a percentage of the income received, thus working as a premium, encouraging people in their work.

We also need to look at how to administer UAI. It is clear that it would need to be distributed within the framework of a broad policy of investment in the healthcare and education sectors.

But those are not the only sectors that matter. Consider highly “human” creative activities, like music, art and storytelling, even news reporting. Among scientists and AI experts who believe in the “singularity” – the idea that AI at some point, possibly as soon as 2040, will overtake human intelligence – there is a growing conviction that such activities are ripe for takeover by AI. Some, like Elon Musk and Stephen Hawking, even fear that AI and machine learning, in repeated cycles of intelligence improvement, could result in a powerful super intelligence eventually causing human extinction. Which is why they call for responsible management of AI development as of now – not waiting for the singularity to happen.

Even allowing that the singularity could happen (how likely is beyond the scope of this article), it is a fact that controlling AI is ultimately a matter of political will. We, humans, can decide not to give economic space to AI-produced art. Or to AI story-writing. We can decide to reward human artists and storytellers, and whatever other “creative” we want to protect, with UAI and reset society’s economic balance whenever AI threatens it.

Featured Photo Credit: GiveDirectly unconditional cash transfers M-Pesa agency, Kenya