The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) has earned over the years persistent bad press for its work to assist in a highly controversial area, family planning. Maligned and misunderstood, its activities have been summarily equated to the promotion of birth control. Yet this is unfairly reductive and wholly misleading. UNFPA likes to describe itself as the reproductive health and rights agency and it does many things besides family planning, working in many other areas in support of life and a better, more sustainable and dignified life. Midwifery is just one such area.

Today, July 31, a UNFPA report on the state of the world’s midwifery is coming out, in the form of a paperback:

The report is published by United Nations Publications, the official publisher for the UN, a unit in operation from the start of the UN in 1945 with the first publication of the UN Charter, and is now responsible for over 400 titles each year. Amazon has dedicated a special place to all UN publications which can be accessed here.

UNFPA led the development and launch of this State of Midwifery report in partnership with the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Confederation of Midwives (ICM) and with the support of an impressive range of organizations, including UN partners (UNAIDS and ILO), major government aid agencies (DFID, USAID, SIDA and Norad), major foundations (Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Johnson & Johnson) and universities (Dundee, Southampton and Yale) as well as Global Financing Facility, GIZ and Save the Children – among others. All concerned international associations were involved, including the International Paediatric Association and the International Council of Nurses.

Now in printed form, the report is a 76-page paperback that will prove useful as a handy reference for health organizations both public and private around the world as well as health experts and workers. The official launching of the report took place on 5 May, chosen because it was this year’s International Day of the Midwife that had the theme “Follow the Data, Invest in Midwives” – which is precisely the objective of this report, the first update since 2014 on the “state of midwifery” across the world.

The report represents an unprecedented effort to document health workers that assist women and children around the world, known in medical circles as the SRMNAH workforce, an unpronounceable acronym that stands for Sexual, Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn and Adolescent Health. The report, however, is especially focused on midwives and assessment of the impact of COVID-19. And it calls for urgent investment in midwives to enable them to fulfill their role.

As UNFPA Executive Director Dr. Natalia Kanem explained on introducing the State of Midwifery report, the situation is dire:

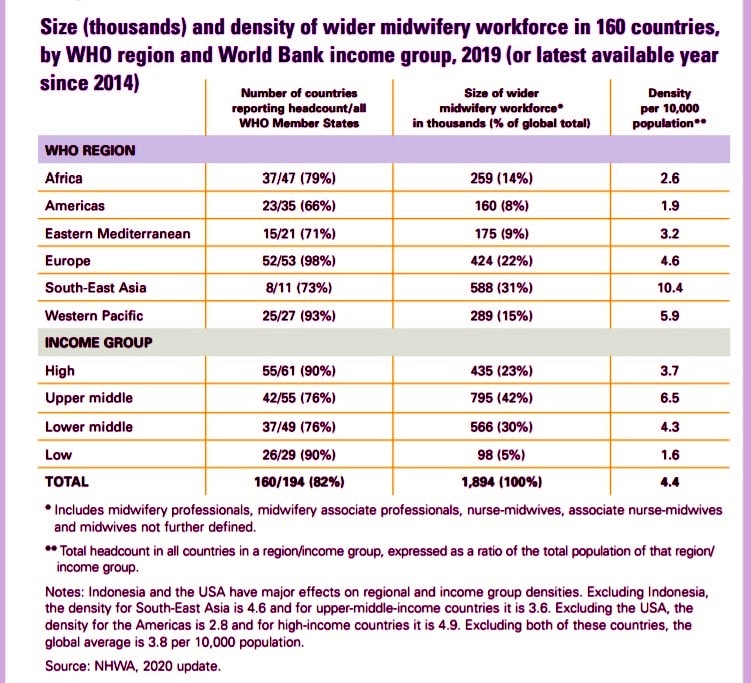

The world is currently facing an acute shortage of midwives. Fully a third of the required global midwifery workforce is missing: The world needs 1.1 million more fully-trained health workers to deliver the necessary healthcare, mostly midwives and mostly in Africa. At current rates, only 0.3 million of these posts are set to be created.

The COVID-19 crisis has only exacerbated these problems, with the health needs of women and newborns being overshadowed, midwifery services being disrupted and midwives being deployed to other health services.

An interesting question arises: How much and what kind of healthcare do women around the world really want for their own maternal and reproductive health? To answer that question, starting in 2016 in India, a broad survey was carried out – the global What Women Want campaign – led by the White Ribbon Alliance. Today, after canvassing 1.2 million women in 114 countries, we have some clear answers. Women’s top priority is “respectful and dignified care”; further down the list comes “increased, competent and better-supported midwives and nurses”; “increased, competent and better-supported doctors” and lastly (but not least) “more female providers”. Most of the other answers women related to the environment in which SRMNAH workers operate. These results clearly show the importance attached by women to the SRMNAH workforce, the quality of health care and the need for midwives.

Midwives Unique Role in Emergencies

The pandemic put the spotlight on the unique role midwives can play in saving lives. The experience of three midwives in Malawi and Namibia is an emblematic case in point (for a detailed account, see p. 32 of the report). They were participants in the ICM Young Midwife Leaders programme which enabled them to take place at the highest level of policy decision-making and thus participate in shaping their country’s response to the pandemic.

Their experiences showed that involving front-line SRMNAH workers leads to better policy decisions at the top because they work on the ground with service users – women, children, and adolescents – and know the situation from the inside. For example, they were able to stop a neonatal intensive care unit from being converted into a Covid-19 center; they raised awareness that a national shortage of cord clamps, caused by diverting resources to Covid-19, was putting newborn lives at risk.

Midwives bring a unique perspective to the policy process when they are involved at the highest levels. To illustrate the point: They can ensure that supplies of PPE are allocated fairly between and within health facilities; they can help design better guidelines for Covid-19 response that recognize the fear felt by midwives working in health facilities at such times and therefore are able to provide reassurance and communicate more clearly what needs to be done.

In short, the report gives a striking demonstration of the importance and effectiveness of midwives as core members of the SRMNAH workforce. When fully educated, licensed and integrated in an interdisciplinary team, midwives can meet about 90% of the need for essential SRMNAH interventions across the life course. Yet midwives comprise just 8% of the global SRMNAH workforce. A huge gap.

How to Fill the Midwifery Gap – What the UNFPA Report Reveals

Filling the gap could be, as UNFPA Executive Director said, “transformative”. As she points out, “Universal coverage of midwife-delivered interventions could avert two-thirds of maternal and neonatal deaths and stillbirths, allowing 4.3 million lives to be saved annually by 2035.”

As mentioned above, fully 1.3 million new “dedicated SRMNAH equivalent” (DSE) workers are needed to close the gap by 2030, and the need is for mostly midwives and mostly in Africa. In general terms, low-income countries can only meet 41% of their need for essential SRMNAH care, which compares to the world’s overall ability to meet 75% of needs.

Factors preventing the SRMNAH workforce from meeting needs include insufficient numbers, inefficient skill mix, inequitable distribution, varying levels and quality of education and training programmes, limited qualified educators (including for supervision and mentoring) and limited effective regulation. Covid-19 has only made matters worse, reducing workforce availability.

For midwives to achieve their potential, bold investment is needed in four key areas: education and training; health workforce planning, management and regulation and the work environment; leadership and governance; and service delivery. Because it’s not just a matter of funding, it’s also a matter of restructuring the public health system and giving midwives their rightful place.

The report also sounds the alarm that some population groups are at risk of restricted access to SRMNAH workers due to age, poverty, geographical location, disability, ethnicity, conflict, sexual orientation, gender identity, religion, etc. “Left behind” groups require special attention to ensure that they can access care from qualified health workers. In this respect too, the pandemic has made matters worse. Health professionals in many settings have lacked sufficient PPE, and there have been violations of women’s rights to respectful maternity care, such as by not allowing labour companions, instituting mandatory separation of the mother and newborn, restricting breastfeeding, and increasing potentially harmful interventions without indication (e.g. caesarean section, instrumental birth, induction and augmentation of labour).

What Can UNFPA and ICM Do for Midwives?

ICM has set up the Young Midwife Leaders (YML) programme to enable young midwives (aged under 35) from low and middle-income countries to learn how to develop as leaders of the profession and to strengthen their national midwives’ associations. This should go a long way to help restructure public health systems and make them more responsive to women’s maternal and reproductive needs as well as ensure that better care is taken of children, from babyhood to adolescence.

UNFPA works hand-in-hand with ICM and supports a YML programme in 11 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean and six states in Mexico. Several cohorts have now benefited from the programme. It is anticipated that the alumni will form a global community of young midwife advocates, sharing ideas and experiences to transform midwifery.

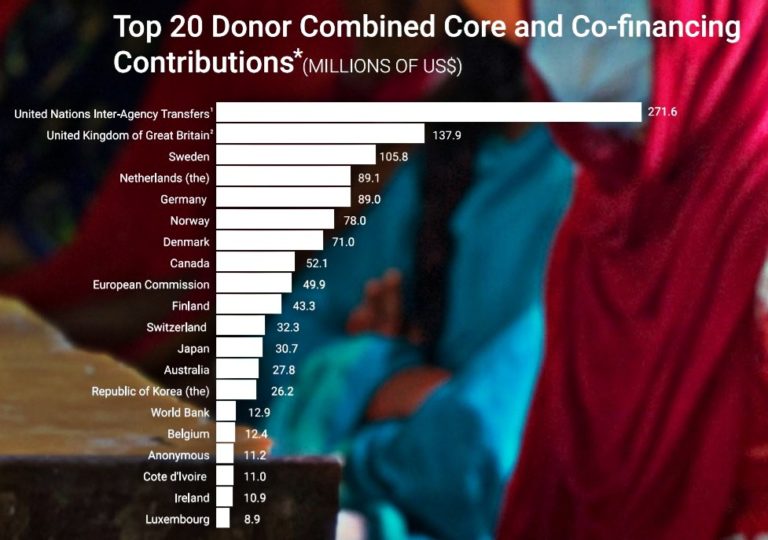

UNFPA has a regular number of programme activities in support of midwifery – but what is most interesting is about UNFPA is that the funding it gets is entirely voluntary. UNFPA, that started operations in 1969, is not an organization like the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) and it’s not a program like the World Food Programme. This makes it different from other UN specialized agencies and forces it to go looking for contributors every year to finance what it calls its “core” – this is totally unlike, for example, FAO that gets regular bi-annual contributions from its member states and can count on a regular core funding to finance what it calls its “regular programme”.

UNFPA mobilizes financial resources from governments and other partners to support programmes that aim to achieve the “three zeros” – zero unmet need for family planning, zero preventable maternal deaths, and zero harmful practices and gender-based violence – and accelerate progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.

UNFP however also relies on what it calls “non-core resources” that include funds such as UNFPA Supplies, the Maternal Health Trust Fund, the Humanitarian Action Thematic Fund and the Population Data Thematic Fund. It also relies on United Nations-pooled and inter-agency mechanisms like the UNFPA-UNICEF Global Programme to Accelerate Action to End Child Marriage; the UNFPA-UNICEF Joint Programme on Elimination of Female Genital Mutilation; and the Spotlight Initiative to eliminate violence against women and girls as well as other instruments such as issue-based, regional or multi-country programmes and initiatives and country-level, multi-level pooled funding instruments. Finally, other resources include consolidated global financing mechanisms and innovative financing such as blended finance, impact investment bonds, financial and insurance products, social entrepreneurship, debt swaps and guarantees.

Clearly, UNFPA has a task raising funds and has responded to the challenge seeking out all possible venues and strategic partnerships. Its top 20 donors include most European countries, Australia, Canada, Japan and Korea as well as one African country (the table, provided on the UNFPA website, refers to 2020):

Unsurprisingly, the United States is not among its top donors. This gives an added urgency to the funding challenges facing UNFPA, and consequently, the limitations to its ability to support midwifery across the world. That is likely to change only if more people realize that UNFPA is not all about birth control, far from it.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists or contributors are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the featured image: Health check at a clinic in Potracancha, Huanuco Region, Peru. © Gates Archive/Mark Makela.