As Russian troops are rolling into Ukraine’s separatist regions of Donetsk and Luhansk, the US is working closely with Europe, and especially Germany to strengthen sanctions against Russia. The first step came yesterday for Germany with Chancellor Scholz announcing the suspension of Nord Stream 2, the just-completed pipeline that was to transport Russian gas directly to Germany (and Europe) and was due to open sometime this summer, after obtaining all the necessary permits from the German authorities.

The Russian financial system is also directly threatened: A “first tranche” of penalties was announced by US President Biden yesterday Feb. 22, that included sanctions against Russian bank VEB (Corporation Bank for Development and Foreign Economic Affairs Vnesheconombank), one of the oldest financial institutions in the country. That means, as the President explained in a televised address, that Russia’s government is cut off from Western financing, and that “it can no longer raise money from the West and cannot trade its new debt on our markets or European markets either.”

The US Treasury Department also released yesterday a list of blocked entities, which included, in addition to VEB restrictions against Promsvyazbank Public Joint Stock Company (PSB), along with 42 of their subsidiaries. Moreover, five Russian commercial vessels, including oil tankers Linda and Pegas, were also on the Treasury’s list.

The EU followed suit, pledging to “react with unity, firmness and with determination in solidarity with Ukraine” and by Tuesday evening, a package of sanctions was adopted by the EU that included the exact same range of sanction measures adopted by the US aimed at limiting Moscow’s access to financial markets.

Likewise, the UK and Japan adopted sanctions.

UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced that five banks have had their assets frozen, along with three Russian billionaires to be hit with UK travel bans. The Foreign Office later announced the UK would also sanction Russian parliamentarians who voted to recognize the two rebel-held areas as independent last week but unlike the sanctions on billionaires, that will take longer to be applied as new legislation is required. Also, in the coming weeks, British firms would be prevented from doing business in the two breakaway areas – a measure similar to the one adopted when Crimea was illegally annexed by Russia in 2014.

Japan Prime Minister Fumio Kishida said today that sanctions against Russia would include prohibiting the issuance of Russian bonds in Japan and freezing the assets of certain Russian individuals as well as restricting travel to Japan. Further details would be provided in the coming days but he reassured his fellow citizens, noting that while Japan has sufficient reserves of oil and liquefied natural gas (LNG) in the short term there should not be a significant impact on energy supplies. However, should oil prices rise further, he said he would consider “all possible measures” to limit the impact on companies and households. And Japan, he said, would continue to coordinate closely with other G7 nations and the international community.

Close coordination on sanctions is a leitmotif of all the sanctions declarations so far, and all of them are clearly indicated as only a first step response. More is to come if Russian troops accelerate into Ukraine.

The sanctions strategy: Coordinated but incremental, leaving room for a harder response to stop sales of Russian oil and gas

All the sanctions adopted so far leave plenty of room for more sanctions should Russia continue with its military action. “If Russia goes further with this invasion, we stand prepared to go further with sanctions,” Biden said.

The ultimate goal – the hardest-hitting sanctions that could be adopted by the West – would be to stop Russia from selling its oil and gas. If sanctions managed to do that, Russia would be badly hurt. Yet Putin, no doubt in the expectation of such a reaction from the West, has created what some observers have dubbed “Fortress Russia”: He has doubled gold reserves, halved the national debt and strengthened the domestic banking system, trying to make Russia as economically strong and autarchic as possible.

But such a “fortress” could not withstand a collapse in Russia’s gas and oil markets. Russia’s economy is heavily dependent on oil and gas that, alone, are responsible for more than 60% of Russia’s exports and provide more than 30% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) and 39% of the federal budget revenue.

Oil and gas are quite simply the backbone of the Russian economy. As Anatoly Chubais told the Russian edition of Forbes magazine in May 2020 oil was a “dead horse” that “Moscow would do well to abandon”. Chubais is a former economic minister to Boris Yeltsin and one of the few liberal economists from that era still in the Kremlin’s good graces, presently heading Rusnano, a state-sponsored technology venture tasked with finding alternatives to Russia’s dependence on fossil fuels. But of course, Moscow hasn’t abandoned that “dead horse” yet so expect sanctions hitting Russia’s oil and gas to bite.

Unfortunately, there are two sides to the story. Europe is also heavily dependent on Russian oil and especially on gas. Suspending Nord Stream 2 makes for good headlines, but it wasn’t operative yet, so it’s more smoke in the eyes than anything real.

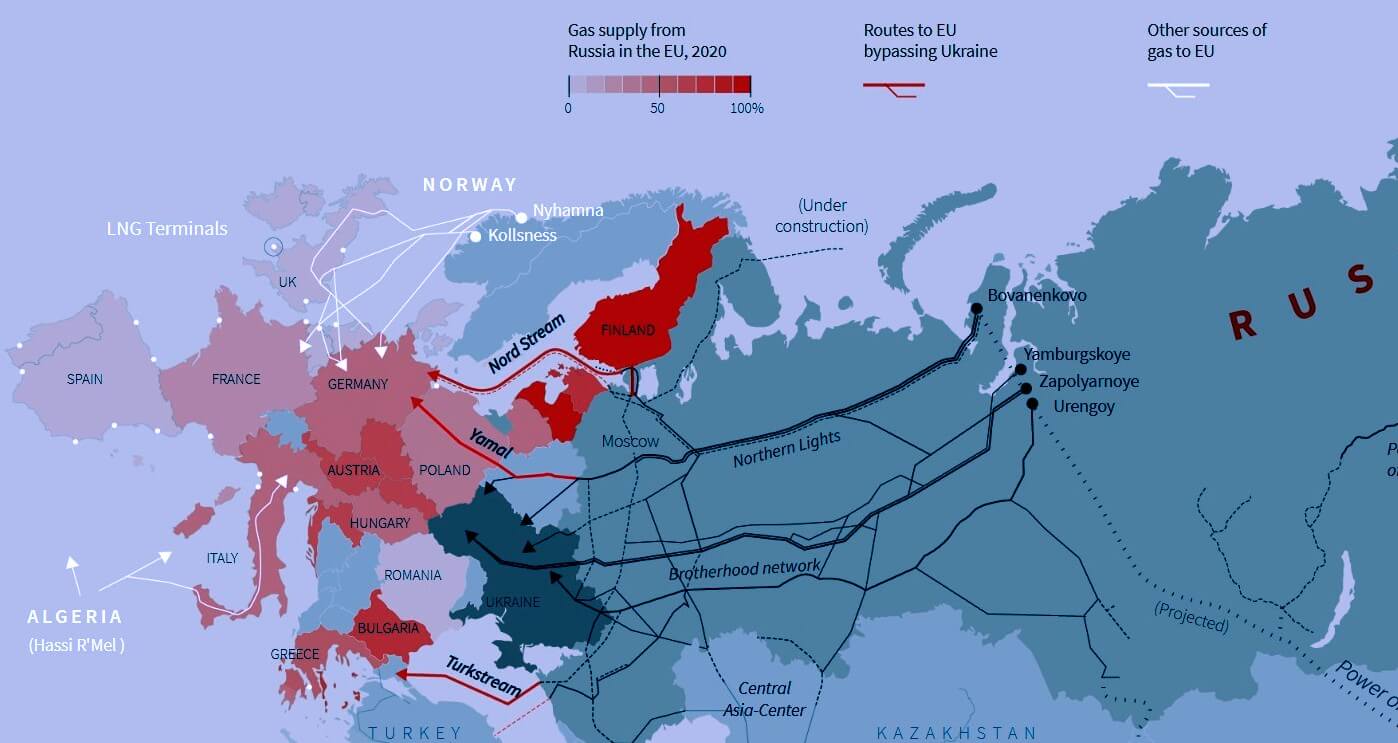

Reuters prepared a remarkable map showing Europe’s dependence that visually speaks volumes and says far more than words can say:

A close examination of the above map reveals that Europe is almost entirely dependent on Russia and that Ukraine (in dark blue) is quite literally at the center of most current working energy routes to Central and Western Europe – moving from south to north, from Bulgaria to Finland (both standing at 100% dependency), and from east to west, from Poland and Austria to Italy, France and Germany (where dependency is very high, hovering around 50%).

Only three routes out of Russia bypass Ukraine, two in the north (Nord Stream and Yamal) and one in the south (Turkstream through Turkey – also with gas coming from Central Asian fields in Azerbaijan).

The rest of European energy comes from North Africa (Algeria), Central Asia (Azerbaijan) and the North Sea (Norway and the UK). Biden has assured Scholz that America would come to the rescue if gas or oil were needed, but America is definitely not next door.

In short, this is a geopolitical mess for Europe. Setting aside the unlikely scenario whereby Russia would completely suspend gas flows to Europe, even small disruptions – given the current post-pandemic global gas reserve shortage and steeply rising price – would, according to a recent analysis by market experts at S&P Global Platts Analytics, cause “deep pain for European energy markets and downstream consumers”. Now that Nord Stream 2 has been suspended, any disruptions to any of the four main gas routes — Nord Stream, Yamal, Ukraine and Turkstream — could send Europe into an energy crisis.

Not so bad for America, of course, as going to war is always a good business proposition. And behind Washington’s constant warnings about the coming war in Ukraine and pushing NATO to maintain a strong position against Russia’s demand for Ukraine neutrality, there is little doubt that one can find the American industrial-military complex which would welcome the lucrative business now that the war in Afghanistan is finally wrapped up.

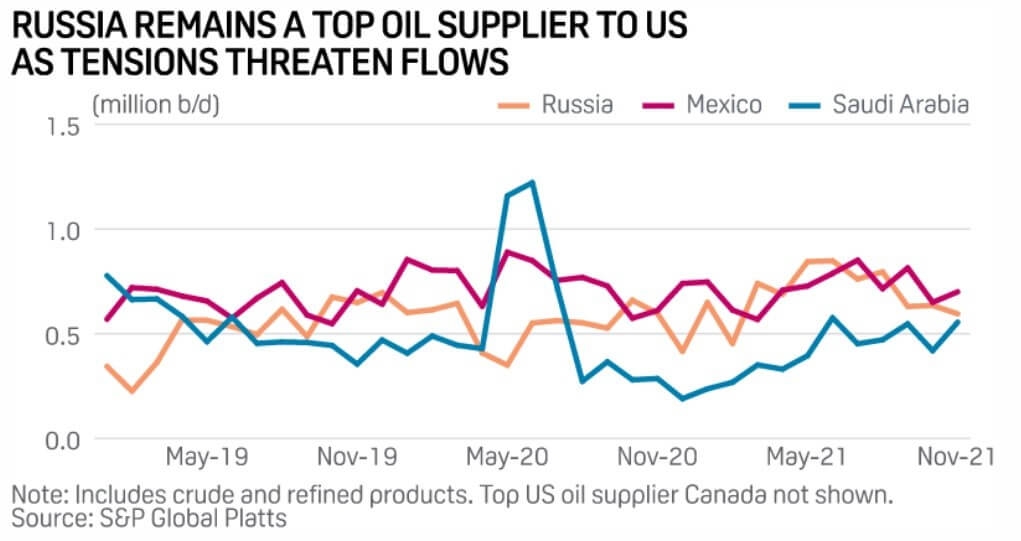

But the situation is not clear cut for Washington either that could suffer a very real blowback if Moscow decided to shut its oil spigots. Because America, although it has its own shale oil and reserves that ensure its autonomy, is also much more dependent on Russian oil than is generally realized. Here’s a just-published analysis from S&P Global Platts market experts that again makes the point visually that Russia is indeed currently among America’s top three oil suppliers:

What happens next: Could Russia cut off gas to Europe?

For the past 20 years, Russian policy has been to develop pipelines to run around Ukraine and try to avoid regional problems there. According to The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), shutting off Ukraine entirely would directly affect only a few countries, in particular Slovakia, Austria and Italy – besides Ukraine itself (even though it no longer buys gas directly from Russia but through a gas buy-back system).

Russian oil Gazprom appears to play a complicated game of slowing gas flows through some pipelines and increasing it in others – for example, the critical Yamal pipeline has dropped to a fraction of its normal flow from Russia and since Dec. 21, it flows in reverse, from west to east, sending German gas reserves to Poland; meanwhile, Nord Stream 1 is flowing at near-maximum capacity rates. Of course, Russia says it is meeting all its contractual obligations on gas export and denies it is disrupting gas flows.

According to the Atlantic Council, Russia could directly attack European gas through covert physical or cyber attacks against Ukrainian and European infrastructures and damage pipelines.

In short, expect the coming conflict in Ukraine to play out in all sorts of ways, including cyberattacks against gas pipeline infrastructure.

How can Europe retaliate? In the short term, Europe has been able to pick up some of the shortages of Russian gas in the past with a boost of liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports and it can do so again. However, there is relatively little flexibility: For now, Norway, Europe’s second-largest supplier, is delivering natural gas at maximum capacity and cannot replace any missing supplies from Russia, its prime minister said. In the end, the only response Europe may have at its disposal is to…cut demand.

Not a happy prospect.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In Featured Photo: Nord Stream 2 pipes. Featured Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons.