U.S. President Donald Trump ordered what he called the “total and complete blockade” of all sanctioned oil tankers entering and leaving Venezuela, a move aimed at choking the Maduro government’s main source of income.

These words, coupled with new related actions, such as the recent pursuit of a tanker en route to Venezuela, may have unforeseen repercussions beyond the Western Hemisphere. For example, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) may view this as an opportunity to pursue longstanding goals regarding Taiwan. Indeed, it could serve as a normative precedent for justifying the encirclement of Taiwan.

“If the U.S. blockades to change political outcomes in Venezuela, China can justify coercive measures against Taiwan on so-called security grounds,” said Craig Singleton, a China expert at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies in Washington.

Furthermore, the Trump blockade affects China economically, as it has been the primary destination for Venezuelan crude oil and the largest buyer of Venezuelan crude (accounting for more than half of Venezuelan oil exports).

China’s claims for Taiwan: brief background

China’s assertion of sovereignty over Taiwan is predicated on the “One China” principle and a selective interpretation of UN General Assembly Resolution 2758, which is not universally accepted as a matter of international law.

While Resolution 2758, approved in 1971 by the UN General Assembly, recognized the PRC and expelled representatives of the Republic of China (ROC), it did not determine Taiwan’s sovereignty or political status for many nations and international bodies.

Rule governing blockades in international law

The international legal framework governing naval blockades is primarily governed by the United Nations Charter, which prohibits the threat or use of force (Article 2(4)), and the San Remo Manual on International Law Applicable to Armed Conflicts at Sea, a widely-recognized compendium of relevant law and custom on the subject by international experts.

Blockades are generally considered acts of war under international law, and are permitted only under strict conditions, primarily during armed conflict. In the absence of a formal war, a blockade would be inconsistent with international rules. As indicated in the San Remo Manual, there are specific conditions for the legitimacy of blockades, including which vessels may be affected, what should be done regarding survivors, and so forth. In part, the Manual states:

“94. The declaration [of a blockade] shall specify the commencement, duration, location, and extent of the blockade and the period within which vessels of neutral States may leave the blockaded coastline.”

With respect to drug cartel actions qualifying as an “armed attack” (and a basis to label such actions “terrorism”), the key question is whether the shipment of drugs into a State (and related non-violent actions) is the type of activity that qualifies as an armed attack.

Regarding a blockade based on drug-cartel “terrorism,” there is no universally accepted rule; but, if claimed as done for self-defense, especially if the host state of the cartel is complicit or incapable of enforcement against the cartel, the blockade should be supported with strong justification and proportionality.

Current U.S. actions

A March 2025 Executive Order 14245 imposed a 25% U.S. tariff on all imports from any country that continues to import Venezuelan oil (in theory, including China). In December 2025, the Trump administration designated the Venezuelan government a “Foreign Terrorist Organization” (FTO), citing alleged links to drug smuggling and human trafficking to justify military action against tankers entering or leaving Venezuela.

Although there has not been a formal statement of the reasons for the U.S. blockade, it seems to be based on claims of expropriated assets and drug trafficking. On this basis, the U.S. has been intercepting/seizing sanctioned oil tankers traveling to or from Venezuela. The result has been a ratcheting up of tensions in the Atlantic and the Caribbean, with the Venezuelan Navy now escorting vessels in response (destruction of alleged drug boats also has taken place in the Pacific).

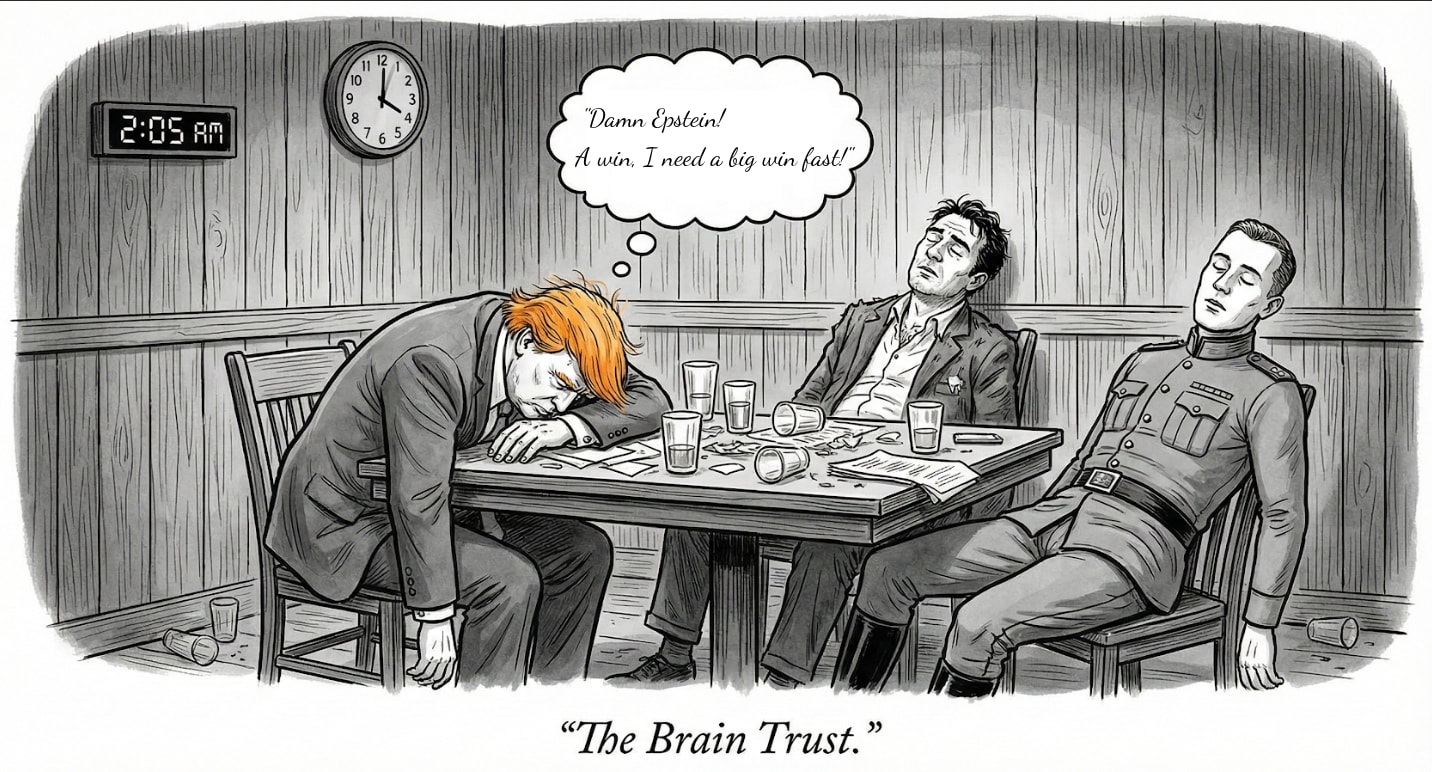

Some experts consider this U.S. claim of “narco-terrorism” and the domestic political attractiveness of military responses to transnational crime as outpacing the law. “This reality is highly problematic, not least for the United States,” writes Michael Schmitt, Professor of International Law at the University of Reading, Affiliate at Harvard Law School’s Program on International Law and Armed Conflict, and Visiting Research Professor at the International Institute of Humanitarian Law.

Responses by other countries

On December 17, 2025, Venezuela requested an emergency meeting of the United Nations Security Council, citing “ongoing U.S. aggression.” The meeting was held on December 23, 2025, and backed by UN Security Council permanent members China and Russia, which criticized the United States for its military and economic pressure on Venezuela, calling its actions “intimidation.” No formal resolution was adopted by the Council.

In Latin America, Venezuela has support from longstanding allies such as Cuba (which depends on cheap Venezuelan oil), Nicaragua, and Bolivia. These governments consistently defend Caracas in regional bodies and maintain close ties through frameworks like ALBA-TCP and Petrocaribe.

That said, the left-wing governments of Brazil and Colombia have not recognized Maduro’s 2024 re-election, but have voiced concerns about the military threats against Venezuela. Mexico’s leader, Claudia Sheinbaum, has said that, regardless of “opinions” about the leadership of Maduro, Mexico’s position is to reject “foreign interference,” and that “the entire world must ensure that there is no intervention and that there is a peaceful solution.”

Related Articles

Here is a list of articles selected by our Editorial Board that have gained significant interest from the public:

China and the U.S. Venezuelan blockade

Beijing has repeatedly signaled that a de facto naval blockade could be a central element of a campaign to gain control of Taiwan. China’s military has practiced blockade-style drills with increasing frequency in recent years around the island, whose government rejects Beijing’s sovereignty claims. The PRC’s efforts to enforce the island’s economic and diplomatic isolation have been augmented by spying, cyber-sabotage, mass surveillance, and disinformation.

To justify its actions to an international audience, Chinese officials could or would portray such a move around Taiwan as a domestic quarantine or law enforcement matter, arguing that the U.S.’s use of a blockade to pressure the Venezuelan government for a political outcome justifies similar “coercive measures” against Taiwan on China’s own “security grounds.” This would be a way to counter efforts to rally any global coalition opposing Chinese actions against Taiwan.

Damage to International Law and Custom

Precedents in international relations are shaped by narrative as much as by laws. When a powerful government decides alone to take, and does take unilateral action to undermine another country, and in this case implicitly to remove a government, the asserted justification for its actions becomes part of the rules for others.

Although President Trump mentioned a “full blockade,” that language probably overstates current U.S. actions. Moreover, Taiwan’s political and legal status is fundamentally distinct from Venezuela’s internal political dynamics, which are those of a recognized sovereign state and United Nations member. This differing legal status, levels of international recognition, geography, and other factors make a possible Chinese blockade of Taiwan distinguishable in crucial ways from the current Venezuelan situation. That said, the erosion of the rules-based international framework applicable to blockades will make it easier for the PRC and other countries to engage in hostile acts. That is a real and present danger.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Cover Photo: USS Sampson (DDG 102). Cover Photo Credit: U.S. Pacific Fleet.