Europe has exported its refugee crisis to north Africa. During the summer of 2017, a combination of European policy making and accurately aimed funding has caused the migrant masses to bottleneck in the north of Africa, among countries that are least able to deal with this issue.

In the Mediterranean, numbers of refugees committing to the arduous and often disastrous voyage across the choppy sea, fell by as much as 70%. This is no random occurrence, but, the outcome of a series of well placed policy measures from the EU to disrupt humanitarian rescue missions in the Mediterranean, whilst giving aid to to north African countries that commit to stemming the flow of people themselves.

The UN now receives funding from the EU to repatriate migrants stuck in Libya, whilst beefing up their coastguard.

Out of this dire situation, a few social enterprises have taken it on themselves to carve out opportunity for those stuck in perpetual limbo. The Pin Project, currently on Kickstarter, seeks to directly support refugees and displaced people by growing their skills and helping them to hold a stable income, in order to rebuild their lives. I spoke to Electra Simon, European lead on The Pin Project, to get more understanding on what it will achieve and how.

Q: Please give me some background into the origins of The Pin Project, what was the main ambition that sparked it all?

Electra Simon: The bleak picture of the refugee crisis is impossible for all of us to ignore. The traditional approach that has sought to ‘contain’ the problem in arid camps may have been acceptable in the short-term, but many refugees find themselves trapped in such camps for years where their skills are neglected and their aspirations crushed. The crucial challenge is to find ways to help these people become self-reliant once more. After reading a report by UNHCR, explaining that craft production was one of the top three ways refugees and displaced persons could begin supporting themselves, Hedvig Alexander – the founder of Far + Wide Collective – came up with the idea of The Pin Project.

Hedvig linked up with ISHKAR and Global Goods Partners, like-minded social enterprises committed to the power of craft, to develop The Pin Project. The immensity of the refugee crisis stretches across the world. To make a difference we believe The Pin Project also must be a global phenomenon. So, we all came together to create this small pin that we hope will make a big difference, providing refugees, IDPs and returnees with training and employment: a framework to re-build their lives.

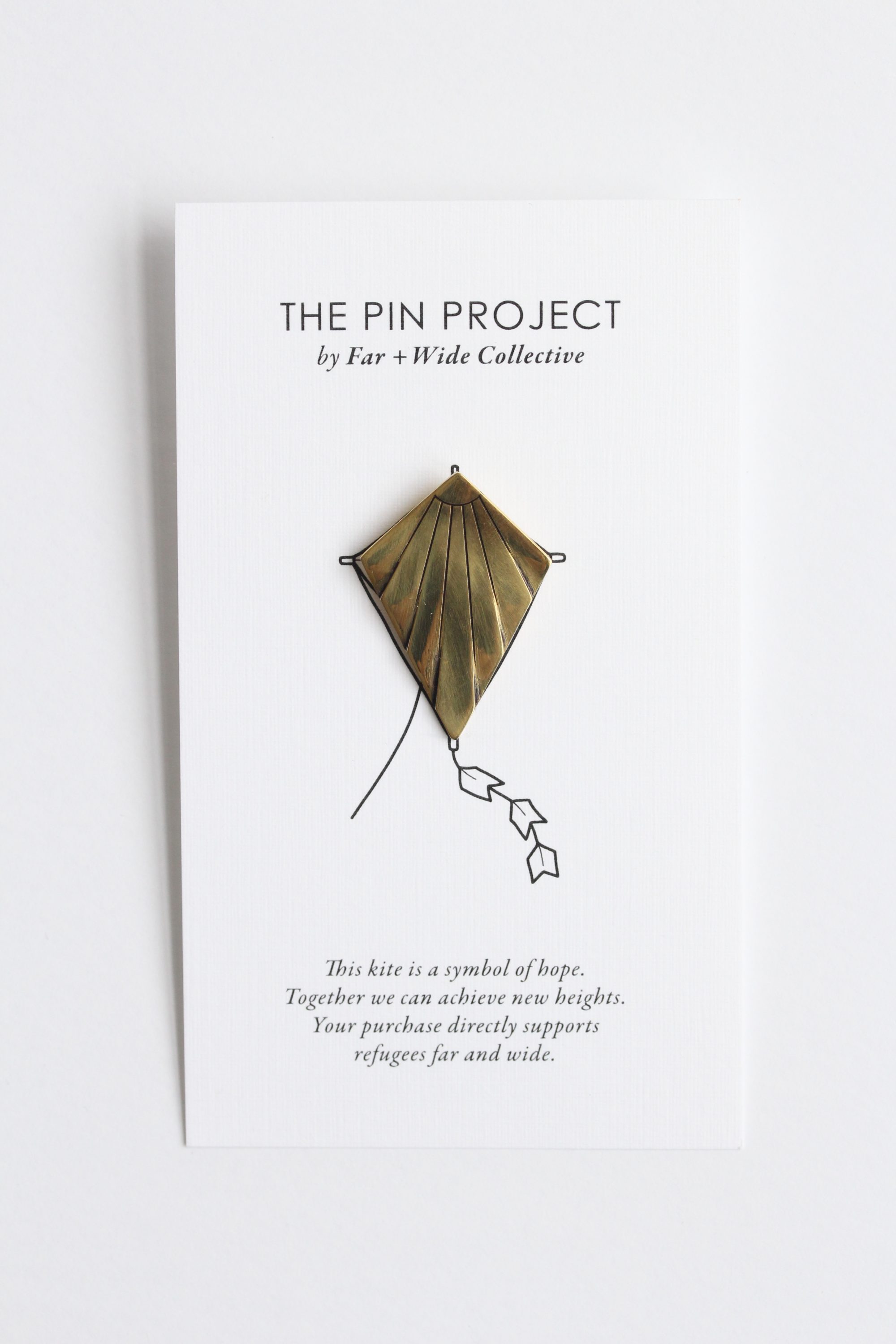

In the photo: The kite pin in presentation form, as purchased Photo credit: The Pin Project

Q: Can you tell me why the pin is a kite shape? what does this seek to represent?

ES: The kite is symbolic. “True courage is like a kite”, said John Petit-Senn, “contrary wind raises it higher.”

Kites do not collapse in strong wind, they fly higher. The Pin Project aims to help refugees, displaced people and returnees rise above the challenges and expectations, despite the crushing circumstances. Jenny Bird, the designer, was inspired by a man making kites for the children at a refugee camp she visited. Touched by the kindness and the hope that the kites represent, she decided to use the symbol for the pin.

Q: Can you explain to me why this project is sustainable in maintaining incomes for displaced people? Does their work stop when the orders stop coming in?

ES: To begin with we will be working with workshops that already exist, the makers of the pins will be their employees, a majority of whom are refugees, displaced people and returnees. However, it all depends on how many people pledge during our Kickstarter campaign. If over 30,000 pins are bought we will be able to create more jobs for more people partnering with other workshops in countries like Bangladesh and Kenya.

In the photo: A new artisan under The Pin Project Photo credit: The Pin Project

Q: Can you give some examples of how refugees and returnees are directly benefiting from this project?

ES: The benefits are three-fold. Firstly, refugees, displaced people and returnees will receive a salary from the project. This is dependent on where they are living, but it will be above the average salary for that region. The salary will reduce their dependency on aid and enable them to support themselves and their family.

Secondly, employment restores a structure to people whose lives have been shattered. The prevailing phenomenon amongst displaced people is boredom and helplessness. Many of these people desperately want to work but are restricted by the institutional apparatus.

Finally, the makers will be trained in how to use the equipment and materials provided. This is a valuable skill that can be used as an outlet for creative expression.

Q: You have a large number of partners and endorsers attached to this project, can you outline how some of them have aided in getting The Pin Project moving and gaining traction?

ES: All three commercial partners: Far + Wide Collective, ISHKAR and Global Goods have worked hard to develop the Kickstarter campaign and forming production partnerships. Our production partners like Turquoise Mountain have helped us by creating prototypes for us to test out the process, they are all essential components in the campaign’s success. As for our endorsers, they have helped us gain momentum and support amongst audiences who care about the cause.

In the photo: The pin being worn on a suit Photo credit: The Pin Project

Q: Lastly, what is the future of The Pin Project in your eyes? What are the goals you hope to achieve and in what time scale?

ES: We really want to make The Pin Project a long-term enterprise. If enough people pledge then more refugees and displaced people will be trained in the craft of jewellery making. After the Kickstarter campaign we would like to start selling the pins through commercial channels and then proceed to test out different designs. We hope to train enough people in craft so that they can also help to train others. Essentially, the trainee will become the trainer.

EDITORS NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com