Our oceans are a dangerous place to live. A recent report authored by scholars from Oxford University found that some parts of the world’s high seas face man-made threats so severe, from climate change to pollution, that these regions are near their ecological tipping point.

One of these threats is lesser known but just as dire, endangering marine animals, the ocean ecosystem, and people alike. This menace is ghost gear: in 2009 the UN estimated that a staggering 640,000 tons of fishing equipment is lost, discarded or abandoned in global waters annually, and this figure does not include gear loss from illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing. Once derelict, this lost gear continues, unintentionally, to catch marine life.

Plastic is so durable in the marine environment that when one entangled animal dies, the debris still has the potential to trap another animal

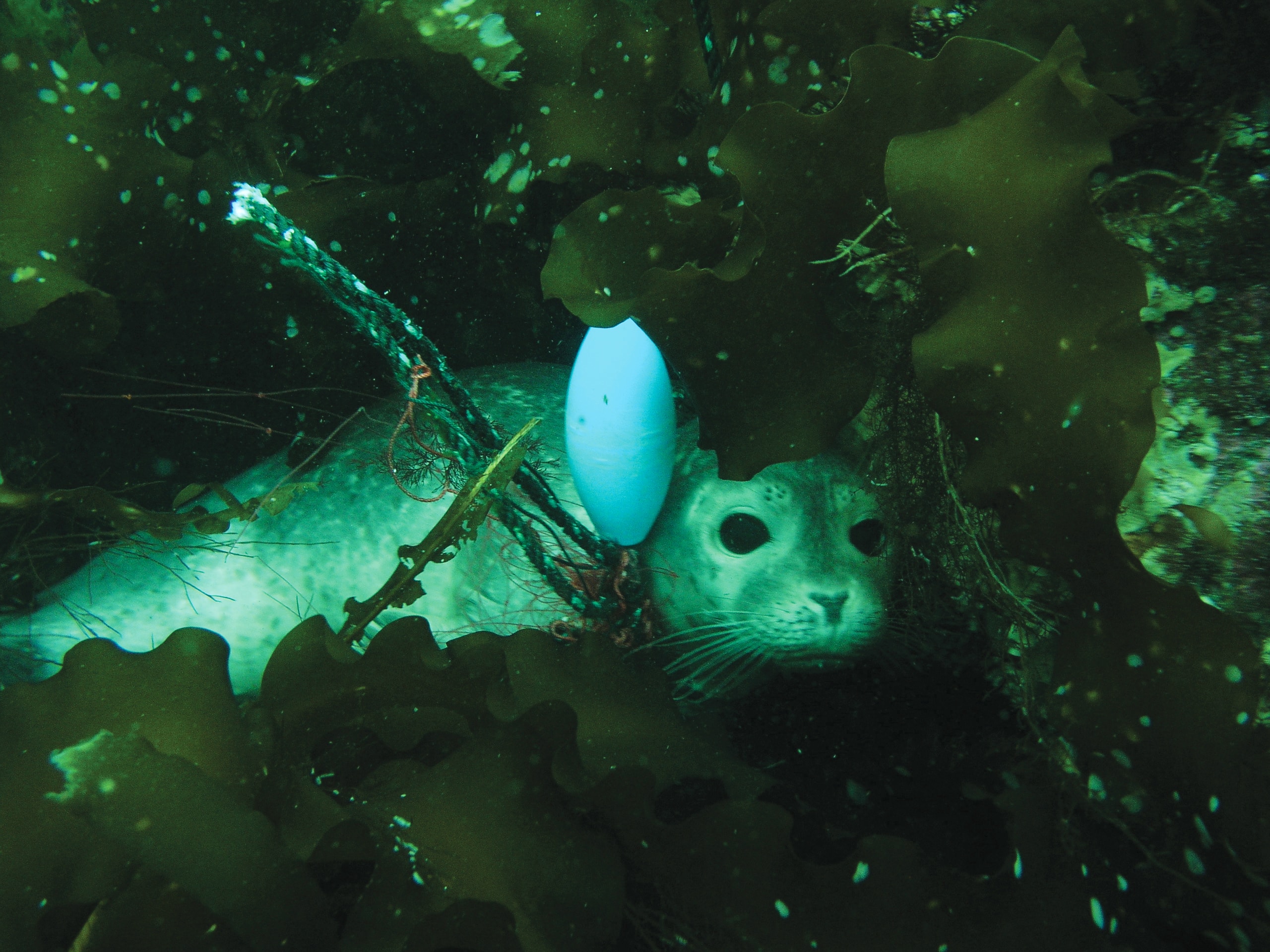

Every year, more than 100,000 whales, dolphins, seals and turtles are caught in this lost, abandoned or discarded fishing gear, or ‘ghost gear.’ Entanglement has various impacts on animals. Smaller animals, like seal pups, may put their heads through rope or monofilaments (single, continuous strands of synthetic fiber commonly used in fishing gear) that then become firmly fixed around their necks or bodies, slowly cutting into their flesh as the young animals grow. Many bigger animals become chronically entangled in ghost gear for months or even years, causing immense pain and suffering, and prolonged entanglement can prevent an animal from feeding to the point of starvation. Animals such as whales towing large amounts of fishing gear become exhausted and may ultimately drown or die of exhaustion. This prolonged suffering can take up to 6 months. The rope and line ligatures in fishing nets can cause amputations and infected wounds, further reducing an entangled animal’s chances of survival.

What lies beneath the surface: Causes of ghost gear

Why does ghost gear enter our oceans to begin with? Much gear loss is accidental. A 2009 report by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) found that the predominant causes of ghost gear are gear conflicts (e.g. when active trawlers pass through an area where static nets are positioned), extreme weather, or strong currents.

In the photo: A seal pup entangled in ghost gear, in the Isles of Shoals, off the coast of Maine and New Hampshire.© – Credit: Steve Whitford / Marine Photobank

Some fishing gear loss is intentional; fishers fishing illegally may purposely abandon their gear to avoid law enforcement. And some intentional gear abandonment is caused by avoidable factors, such as a lack of accessible onshore gear and waste disposal facilities.

While the causes of ghost gear are varied, derelict fishing equipment is consistent in its durability. Most ghost gear is made of plastics that take centuries to decompose into microplastics, some as long as 600 years. Such plastic is so durable in the marine environment that when one entangled animal dies, the debris still has the potential to trap another animal. A single lost fishing net can be enormous, the size of a football field. Other forms of ghost gear, like packing bands commonly used around bait and packing boxes, may be smaller, but just as deadly, frequently entangling seals and sea lions.

How ghost gear harms marine animals

Ghost nets have driven some species to the point of extinction. The vaquita porpoise, a little-known species found only in Mexico’s Gulf of California, is the world’s most endangered marine animal, with an estimated 25 individuals left on earth. Ghost nets are the single biggest contributor to the vaquita’s near eradication. Local fishers use illegal nylon gillnets to catch a fish called the totoaba, a critically endangered species sold illegally in China where its bladder is used in traditional medicine. Once abandoned, these gillnets don’t just catch the totoaba, itself a critically endangered species; they entangle and drown vaquitas.

In the photo: Christina Dixon of World Animal Protection observes the collected debris at beach clean-up on Perranporth beach, Cornwall, UK. Credit: © World Animal Protection / Greg Martin

The impact of ghost gear doesn’t end with snaring animals at sea. Throughout their long life cycle, fishing gear and other debris in the oceans slowly break down to become the size of grains of sand – known as ‘microplastics’. These minute plastic granules are found in water and sediments and may have a toxic effect on the food chain that scientists are only beginning to understand.

Reports show that over 800 species of marine life are affected by ghost gear. It’s found in every ocean and sea on the planet; even remote Antarctic habitats experience such pollution. And this gear is known to travel long distances from its point of origin, accumulating in hotspots around oceanic gyres. The tags of lobster pots set in Maine and Newfoundland have washed up in Scotland, making the transatlantic journey of over 3,000 miles; nets found in Hawaii, an oceanic hotspot, have traveled from as far away as Asia.

Ghost gear doesn’t just cause harm for animals – it negatively impacts seafood and marine industries themselves. For every 125 tons of fish caught, about a ton of ghost gear is left behind. Derelict fishing gear causes large-scale damage to marine ecosystems and compromises yields and income in fisheries; it’s been estimated to have caused a 10% decline in fish stocks globally. U.S. researchers have estimated, for example, that a single ghost net can kill almost USD$20,000 worth of Dungeness crab over 10 years. Governments and marine industries spend many millions of dollars annually to clean up and repair damage caused by ghost gear. Ghost gear is a true global problem, one that requires global solutions at scale.

Hope for ghost-gear-free seas

But the good news is that awareness of the ghost gear problem, and its urgency, are growing. In 2015, World Animal Protection launched the Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI), the first cross-sectoral alliance working to drive solutions to the ghost gear problem worldwide. The GGGI’s strength lies in the diversity of its participants, including representatives from the fishing industry, the private sector, academia, governments, intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations. The GGGI aims to offer achievable guidance for the seafood industry to meaningfully reduce marine litter, and is working collaboratively with the fishing industry to do so.

In the photo: World Animal Protection staff visit Steveston Harbour Authority in British Columbia, Canada. Steveston Harbour Authority is working with partners Aquafil and Interface Inc. on a net recycling program to turn old fishing nets into carpet tiles and other products. Credit: © World Animal Protection / Rob Trendiak

Earlier this year, the GGGI launched a new Best Practice Framework for the Management of Fishing Gear, which recommends practical solutions and approaches to combat ghost fishing across the entire seafood supply chain, from gear manufacturers to port operators to seafood companies. Advancements to fishing gear design, sourcing decisions, fishing policies and disposal of end-of-life fishing gear can significantly reduce the impact of ghost gear on marine ecosystems, livelihoods, and wildlife. Bureo, a Chile-based GGGI participant, for example, makes skateboards, sunglasses and other from recycled fishing nets. Their recycling program in Chile, ‘Net Positiva’, provides fishing net collection points to keep plastic fishing nets out of our oceans. Their program protects wildlife and supports local fishing communities through financial incentives, preventing harmful materials from entering the ocean.

And these measures aren’t just theoretical; the Best Practice Framework also includes accompanying case studies on how changes have been achieved in practice by those working to prevent ghost gear. Such approaches include net recycling programs, derelict gear removal initiatives, and fishing management policy adjustments, among others. GGGI participant World Animal Protection Canada is, for example, supporting a derelict crab trap recovery project in the northern British Columbia Dungeness crab fishery that will set the stage for a longer-term approach to recovering lost gear and addressing economic and ecological impacts of lost crab pots. Despite having a well-managed fishery and undertaking stray pot removals each year, fishers in the area report that there are many stray pots underwater that have not been retrieved due to logistical and financial limitations. Lost crab traps can continue to “ghost fish”, cause navigational and safety hazards to other vessels in the area, detrimentally impact the marine habitat, and potentially entangle marine mammals.

As the seafood industry looks to become more sustainable and limit its impact on vulnerable marine ecosystems, seafood companies, retailers and fishing industry representatives have been very receptive to the practical guidance developed by the GGGI through a wide public consultation. Surveys during the consultation period showed that over one-third of participants ranked ghost gear as a moderately or highly significant issue.

On World Oceans Day this year, Young’s Seafood’s Head of Corporate Social Sustainability David Parker, a GGGI participant and Steering Group member, commented that: “A clean and healthy marine environment is imperative to great quality and sustainable seafood, and what’s good for our oceans is inherently good for our industry. We are pleased to have had a hands-on role in the GGGI since its inception, bringing a seafood industry perspective through the network of our supply chains around the world.”

Parker continued, “We believe that sustainable practice is the only way to safeguard the future of fish for generations to come. As a leading processor of responsibly sourced fish, we strive to do the right thing, always. Since we started out, the GGGI has helped to reduce litter in the world’s oceans in three major ways. Firstly, through direct on-the-ground action with divers retrieving hundreds of lost fishing gear to be recycled. Secondly, raising awareness globally through innovative projects and political awareness work with the FAO, which has the potential to translate into lasting policy. And, thirdly, by providing recycling facilities for end-of-life gear with end-use developments such as transforming this plastic into anything from skateboards to bikinis to sunglasses. At Young’s, we’ve been supplying fish for more than 200 years. We believe that sustainable practice is the only way to safeguard the future of fish for generations to come.”

It is our hope that companies will start adopting the framework’s recommendations in their Corporate Social Responsibility programs and in standard-setting and certification programs in the future. “The Best Practice Framework fills a vital need for the seafood industry,” said Jonathan Curto, Sustainability Coordinator at TriMarine, a GGGI participant. “Reducing ghost gear is important to all of us, and the practical guidance and case studies the Best Practice Framework provides will help companies to implement positive changes and processes across the seafood supply chain. Participants in the GGGI hope that the document will not only protect the environment for wildlife and other marine users, but also increase productivity for suppliers and retailers.”

Sustainable Development Goal 14: Protecting our oceans

Pressure is also growing for countries to take an active role in reducing marine litter. After all, our planet’s wellbeing – for people and animals alike – depends on healthy oceans, and here lies the United Nations’ responsibility and mandate.

In 2015, the UN established 17 ambitious global targets, known as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Goal 14 is entirely focused on the world’s oceans or “Life below the water”. The first target under this goal, target 14.1, concentrates on marine pollution and calls for a significant reduction of marine pollution of all kinds, including ghost gear, by 2025. As part of its far-reaching efforts to protect our oceans, the UN also held the first-ever Ocean Conference this June at its New York headquarters. The aim of the event was to turn Goal 14 into tangible, positive action items to drive change for the world’s oceans and the life within them. At the World Economic Forum in January this year, Peter Thomson, President of the UN General Assembly, said: “The ocean underpins trade, tourism, employment and food security. Therein lies the call to action, since the oceans’ health is vital to humanity’s well-being, and since it is human activity that is causing the decline of the oceans’ health, then it is our responsibility to correct our actions and set about reversing that decline.”

Real action, including encompassing solutions, is needed now, and this was very much the spirit in which countries from all over the world gathered at the UN this summer. World Animal Protection was there to encourage and motivate countries to recognize that the issue of ghost gear greatly affects our oceans and the life within them. After all, ghost gear is four times more likely to impact marine animals by trapping, injuring, mutilating or killing them than all other forms of marine debris combined.

We were heartened to find at the Ocean Conference that countries very much acknowledged this shared responsibility to protect our oceans. More than 1,393 commitments were pledged to take action and reverse the global decline in ocean health. And ghost gear featured high on the agenda, with an incredible 11 countries signing Statements of Support for the Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI). These countries — Belgium, Sweden, New Zealand, Tonga, Panama, The Netherlands, The Dominican Republic, Tuvalu, Samoa, Palau and Vanuatu — all welcomed the GGGI and publicly supported its commitment to improve the health of marine ecosystems, protect marine animals from harm, and safeguard human health and livelihoods.

In the photo: World Animal Protection and the Gulf of Maine Lobster Foundation, in partnership with local fishermen, removed ghost fishing gear off the coast of Portland, Maine. The group removed 147 derelict traps and 1,000 pounds of rope and line. Any animals found inside lost traps (mostly crustaceans) were released back into local waters, and 44 traps in good condition were returned to their owners. Gear that could not be reused was recycled by the NFWF Fishing for Energy Program. Credit: © World Animal Protection / Kristian Whipple.

In addition, Belgium partnered with the GGGI as a key sponsor and has pledged significant financial support to deliver a pilot project on the marking of fishing gear in the South Pacific. While seemingly simple, marking fishing gear to identify who owns it and where it originated is hugely important. Gear marking allows fishers to retrieve gear they have accidentally lost, dissuades them from deliberately abandoning it, and helps identify fishing activity happening illegally. Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) fishing, a global problem, is a major contributor to ghost gear.

Mr. Didier Reynders, Belgian Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign and European Affairs, said: “We must strive to make the private sector, fishing industry, academia and governments work together to reduce the impact lost gear has on the economic sector, food security and most importantly on marine ecosystems. Certification and marking of gear to make it traceable and recycling of retrieved materials are some of the most promising solutions. My country supports the gear recovery initiative and recycling as a principle.”

Ahead of the Our Ocean Conference taking place in Malta at the start of October, we are hoping to see more Governments pledging a commitment to address the issue of ghost gear by implementing national marine litter plans and joining the Global Ghost Gear Initiative. Since 2014, Our Ocean conferences have invited world leaders to look forward and respond, delivering high-level commitments and transforming the challenges ahead into an opportunity for cooperation, innovation and entrepreneurship. We are hoping that we can build on the momentum of the UN Ocean Conference and see commitment be translated into action.

A call to action for sea life

The time to act for the world’s marine life is now. A 2016 study published in Marine Policy by Wilcox et al. found fishing-related gear to be one of the three sources of marine litter – along with balloons and plastic bags – posing the greatest entanglement risk to marine wildlife, including seabirds, sea turtles and some of our most iconic marine mammals like whales and dolphins.

Businesses also have a crucial role to play, by getting involved with the Global Ghost Gear Initiative. To learn more, visit www.ghostgear.org. You can also find the GGGI’s Best Practice Framework for the Management of Fishing Gear and contact the GGGI for more information via our website.

Government action is vital. We urge national and international representatives from countries around the world to join the GGGI’s efforts to eliminate ghost gear and create safer, cleaner oceans.

And how can you take action to help combat ghost gear? World Animal Protection’s Sea Change campaign works around the world to reduce the volume of ghost gear, remove and recycle such gear from the oceans, and rescue entangled animals. You can visit our website to learn more and join our mailing list, at www.worldanimalprotection.us.org/seachange. In addition, as a consumer, you can also become educated on where fish comes from before buying it and understand which fisheries you are buying into. As Martin Stelfox from the Olive Ridley Project, a GGGI participant, highlights: “As consumers, we have the power to protect our fisheries and stock levels.”

If advocates, governments, and industry come together as committed partners and champions, we believe that we can achieve ghost-gear-free seas. The future of our oceans – and their inhabitants – depends on it.

In the photo: Rescuers were able to untangle the gill net from this entangled sea lion in California. Credit: © Kanna Jones / Marine Photobank

World Animal Protection is an international non-profit animal welfare organization that has been in operation for over 30 years. The charity describes its vision as: A world where animal welfare matters and animal cruelty has ended.

World Animal Protection is an international non-profit animal welfare organization that has been in operation for over 30 years. The charity describes its vision as: A world where animal welfare matters and animal cruelty has ended.