This is How The Protests Played Out. Construction of the Line 3 pipeline in Minnesota is facing determined opposition from protesters who have been active since December 2020, when work on a replacement pipeline through the state began. I traveled there recently from my home in Detroit, Michigan, to participate in the protests. My trip covered a week of activity, and this is an account of my experience.

The trip began with a couple of rallies, and I spent a few days in campsites that have been set up for people who are organizing against work on the pipeline. I took part in direct action one day and was arrested for the first time.

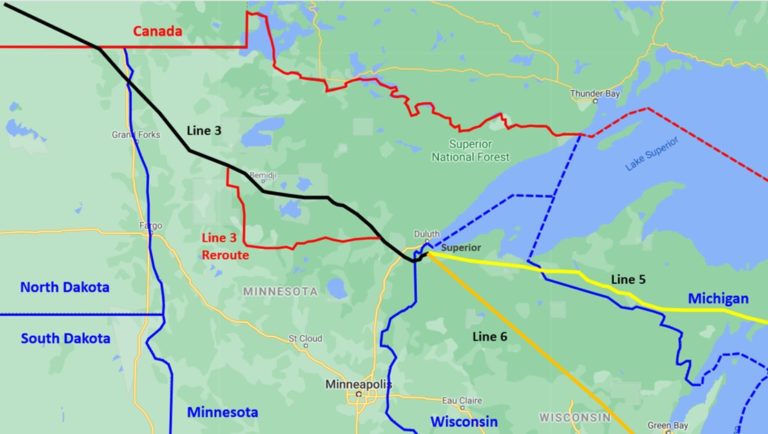

Line 3 originates in Alberta, Canada, and runs for about 1100 miles (1770 km), terminating at a huge refinery in Superior, Wisconsin, at the westernmost point of Lake Superior. Most of its length in the U.S. is in the state of Minnesota, with small stretches in North Dakota and Wisconsin. The pipeline is about 50 years old and is deteriorating.

The Canadian oil company Enbridge owns and operates the line, and is working to replace the old line with a new pipe that expands capacity. Not all of the new pipeline route follows that of the existing line, and many of the protests occur in the areas where construction on the new route is underway.

Pipeline Protests in Minnesota

My trip began with a ten-hour drive around the southern part of Lake Michigan for a rally and march the following day in St. Paul, near Minneapolis, on Jan. 29th. The rally was sponsored by the Minnesota chapter of 350.org, MN350. I’m in the picture below, holding the “Climate Chaos” sign.

There were 600 people at the rally. Many were Native Americans from the surrounding area, mostly Ojibwe and Dakota. The Native communities are organizing and leading many of the protest actions.

The pipeline route passes through treaty lands and crosses 227 bodies of water (including the Mississippi River, twice), posing a threat to wild rice cultivation in many of the lakes along the route. This is in violation of treaty rights established with the federal government. Hence the name the protesters took: “Water Protectors.”

The pipeline delivers tar sands oil from Alberta, Canada, one of the most carbon-intensive forms of fossil fuel. Once operational, it would produce the CO2 emissions of 50 new coal-fired power plants.

Pipeline construction leads to thousands of out-of-state workers being brought into rural areas, many in close proximity to reservation lands. They are housed in temporary settlements called “man camps,” and these are associated with increased levels of violence against indigenous women and girls. This issue is receiving increased attention, and is known by the title “Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women (MMIW).”

In my home state of Michigan, there are protests over our Line 5, which begins at the same refinery in Superior where Line 3 terminates. The refinery converts the heavy crude tar sands oil into a lighter grade of crude and pumps it east via Line 5, which runs for over 1,000 km with most of its length in Michigan.

From Superior, it stretches across the full length of our state’s Upper Peninsula, crosses the bed of the narrow Mackinac Straits into lower Michigan, and then crosses the St. Claire River above Lake St. Clair near Detroit, passing back into Canada at Sarnia, Ontario. Most of the oil in the pipeline flows back into Canada and is sold for export from ports on the East Coast.

Line 5 is also operated by Enbridge, and is over 50 years old. Michigan Governor Whitmer has revoked the easement for operation of the pipeline, and ordered Enbridge to stop pumping oil through the line by mid-April. This has gone to the courts, and Enbridge is of course resisting the shutdown order.

Much of the opposition to Line 5 is centered around the passage through the Mackinac Straits. Enbridge proposes to replace that length of the pipeline with a tunnel through the bedrock under the straits.

Opposition to Line 3 in Minnesota is directly tied to opposition to Line 5, as the same oil travels through the lines via the refinery in Superior.

Pipeline Protests in Wisconsin

During the rally in St Claire, I heard about another pipeline protest planned for the next day in Superior, Wisconsin, about a two hour’s drive north, and I headed up there early the next morning. This was another rally, in front of the Douglas county courthouse, and across the street from old office space for Enbridge.

Native Americans were again playing a leading role, and at one point a mournful song was played over speakers, repeating seven times. The song was in the Ojibwe language, with the lyrics translating to “Water we love you, water we thank you, water we respect you.”

The protest ended up with a die-in, with everybody playing the part of dead bodies for about 16 minutes, which seemed quite a bit longer in the cold (about -6 C). This symbolizes the effects of poisoning our land, air, and water with fossil fuels.

Back to Camps in Minnesota: For “Direct Action” Protests

After the protest in Superior, I headed back into Minnesota to visit a couple of camps that I’d heard about, where activists are staying in tents and working in opposition to Line 3 construction. There are four camps that I know of: The Giniw Collective, The Red Lake Treaty Camp, Camp Miigizi, and The Welcome Water Protectors Center at the Great River. The last one is close to one of the pipeline crossings of the Mississippi River, which has headwaters in Minnesota.

I first visited Camp Miigizi, which is the newest encampment, with little more development than a short dirt driveway connecting the campsite to the road. Miigizi is Ojibwe for “bald eagle.” Many tents are set up in the camp, with a central fire pit. A lone red dress hangs from a tree where cars are parked on the road, symbolizing the MMIW crisis.

When I arrived, there were several people chopping firewood with axes, and I joined in with that effort for a few hours. I also stayed for a couple of days at the Water Protectors Center, which is a larger encampment centered around a residence.

Visitors are welcomed in the camps and provided with meals and space to stay in a tent if one is available. Small propane heaters or wood stoves are used to heat the tents. The wood stoves are quite effective heat sources but have to be restocked with firewood during the night. I woke up from the frigid cold a few times when the fire died down. Some of the protest organizers stay in the camps full-time and sleep in tents every night through the winter.

While I was staying in the camps, I learned about “direct action” protests happening at a nearby pipeline construction site on the Fond Du Lac Reservation.

Direct action involves efforts to disrupt the work of the pipeline construction crews. I decided to take part and agreed to take a role where I would obstruct work.

The plan called for me to lock myself to one of the excavator cranes, along with another water protector, a Native American woman who lives in the area and is active in the cause. Her name is Lish LaBarge. She is brave, fierce, and dedicated, and is also the mother of young children. We were given a length of square pipe with a bar in the center which we could attach chain links to, from lengths of a small chain that were connected around our wrists.

A flood of visitors came into the camps to participate in the pipeline protests that day, February 2nd, many carrying signs that they had prepared themselves. There were over 50 protesters in action, once we made it on-site where the pipeline was being laid into the ground.

We marched from our cars for about ten minutes along the length of the pipeline, which was lying in a freshly dug trench, yelling and singing all along the way. We came to a group of six large excavator cranes that were working on laying a pipeline into the trench.

Our square pipe was quickly brought out, and we scrambled to find a part of the nearest crane to lock ourselves onto. We found a huge link on the front of the crane, which operates as a hitch. The pipe slid easily through the link, and we attached our chains so that we each had one arm locked inside the pipe, up to the elbow. The crane was shut off, and we settled in place for the duration of the action.

Pipeline security personnel and police arrived on the scene quickly. Our action took place on reservation land, and the Fond Du Lac Reservation police responded, along with Minnesota state police forces.

There is a large police presence along the pipeline route, and I was told that Enbridge is supplementing the funding for police in the counties where pipeline work is happening, for extra hours spent responding to protests.

A stand-off ensued, as the police made announcements that the protesters were trespassing, and we in turn continued to chant and yell. Some of us marched along the pipeline route between the cranes, all of which had stopped working.

The police offered several warnings and issued orders to disperse, and the bulk of the protestors ultimately left the worksite before being threatened with arrests. Our goal with the pipe on our arms was to keep the crane out of operation for as long as possible.

We were in place for just a couple of hours before the workers were able to remove the heavy link from the crane, without having to cut apart the pipe that we had locked our arms into. Lish and I were then removed from the excavator by the workers and police, and placed under arrest by the reservation police.

Once we were separated from the crane, and could no longer disrupt work on the pipeline, we unhooked our chains from the square pipe and removed our arms. We were then handcuffed and loaded into the back of a reservation police car, and taken to Carlton County jail.

Lish and I were the only ones arrested at that action, but there have been more than 120 arrests of Line 3 protestors since December, in numerous direct actions.

Life in Jail

The ride to jail was not long, and Lish and I were separated once we arrived. I was booked in, had my mugshot taken, and was placed in a holding cell to await bail. I thought I was putting on a brave face for the camera, but I got a look at the picture and was disappointed to see that I just looked miserable.

I was expecting to be released fairly quickly, after my bail would be posted by a legal support group that works with the protesters. Several hours passed, however, and I was given a tray of food for dinner. I had avoided eating much before the action, as I was expecting to be locked in place for several hours and not be free to visit a bathroom. I was hungry enough to eat the food and appreciate it, though it wasn’t so tasty that I’d go back again for more.

After the meal, I had to change into jail clothes and was moved from the holding cell to a jail cell, which was entirely empty except for two thin stacked beds, a sink, a toilet, and a metal desk and stool that were attached to the wall.

Because of precautions for the coronavirus, each of the cells was occupied by just one person. I had been a little worried about potential exposure to crowds and the virus, but everyone at the protest action and everyone in the jail seemed to be taking the risks seriously, and I didn’t see anyone without a mask.

For the most part, I was treated pretty well by the jail staff. They’ve seen many other protesters come through, and I think we’re not treated the same as your typical rowdy drunk or wife-beater.

My new cell was one of a group of about six that opened into a small central common area, and most or all of the other cells were occupied. The walls were made of cinderblocks, with a few square feet of open space by the door, with vertical bars in place as a barrier.

I was told by the guard as he was taking me in that I’d have one hour each day to spend in the common area, in addition to mealtimes that were also to be taken there. I picked up one of two books in the common area before my cell door was locked—a copy of Robert Ludlum’s “The Bourne Supremacy.”

I brushed my teeth and had something like a sponge-bath with a washcloth at the sink, with items from a toiletry kit that I was given before being taken to the cell. From there I got just a small hint of how dreadfully boring it must be to spend any amount of time in jail. A couple of hours went by, and I read a little bit of the book before the lights went out at 10 o’clock.

My fellow inmates had been making a bit of noise the whole time, but they seemed to be really energized by the lights going out. One fellow had a peculiar fascination with his toilet, which was very loud when flushed. He proceeded to flush it about every five minutes, and I resigned myself to a sleepless night.

After a bit more than an hour of this, a guard came and opened my cell door and turned on the light. He said that I had just made bail, which made me quite happy. I changed back into my own clothes and was released into the lobby, where several people were waiting for me, including fellow protesters and a pair of legal support volunteers. I learned that there had been a delay with my bail, which was set at $3,000—much more than is typical for protester arrests, possibly due to my being an out-of-state resident.

Another Line 3 protester, Jeffrey Haining, had been released from the same jail shortly before me. A day earlier, Jeffrey had jumped onto a pipe that was suspended from a crane and stayed in place for over seven hours before being removed and arrested. He had been kept overnight in jail.

Jeffrey and I were led outside and honored by two of the other protesters who had come out to the jail for us. These were Native Americans, and they had brought a round flat drum with them. I was deeply moved as they sang and beat the drum for us, there, by the jail parking lot in the cold, close to midnight.

With their song, the water protectors were thanking us for taking a stand against the pipeline, and for joining their fight to protect us all from the destruction of our changing climate. A memorable night for all of us.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: A flood of visitors came into the camps in Minnesota to participate in the protests on 2 February 2021, with many carrying signs that they had prepared themselves: There were over 50 protesters in action. Photo Credit: Charles King’s own photos illustrate the article.