The Impakter team, deeply saddened at the tragic loss of lives in the airplane crash near Addis Ababa, joins the Secretary-General of the United Nations in conveying their heartfelt sympathies and solidarity to the victims’ families and loved ones, including those of United Nations staff members, as well as sincere condolences to the Government and people of Ethiopia.

Editor’s Note: The world’s governments are gathering in Nairobi from the 11-15 March 2019 for the annual UN Environment Assembly (UNEA). Bobby Peek of groundWork South Africa explains how we can make progress with the SDGs, more specifically Goal 12 — ensuring sustainable consumption and production patterns — by working toward a safe, circular economy.

Fundamental Flaws With the SDGs

GroundWork takes the view that in general the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in themselves will not lead us to a path of sustainable development — many environmental justice organisations such as groundWork take the view that the SDG’s are “a distraction from the real work of fighting poverty done by social justice activists” because the causal links between systems of power that create poverty, waste, disease and climate change are fundamentally not addressed in the SDG’s. Mandatory measures are in our view necessary but lacking in many of the goals, one telling example being the omission of mandatory measures to address climate change through mandatory greenhouse gas emissions-cut goals in the SDG 13 — “Climate action.”

However, to make progress to “ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns” we need to implement this SDG goal in a manner that addresses this fundamental delink outlined above. Sustainable consumption and production is plagued by industry secrecy and unaccountability of the use of chemicals and products along their value chains. More alarmingly at this time approaches such as “cleaner-fossil fuels” distract us from the reality that, firstly it is not possible, and secondly we need to use whatever little carbon budget we have left to invest in a Just Transition, including the move towards renewable technologies that are socially owned.

Homeowners and businesses can participate by doing little things such as metal recycling and using renewable energy sources. There are Commercial Scrap Metal Recycling Services as well as scrap metal merchants that help collect scrap metal instead of dumping them into our landfills. Everyone can contribute to achieve a more sustainable way of living.

SDGs – The Tools we Have at Hand

However the SDGs are the tools that have been globally agreed upon to guide us towards sustainable development, and if these SDGs were to be meaningfully integrated at all levels into our development planning then arguably no other SDG has such a cross cutting importance for the fulfilment of other SDGs as SDG 12. Production and consumption drives resource extraction and production of raw materials and food, which results in waste, pollutants and climate change. The elite priority for economic growth is pushing ever more people into market based consumption to secure basic needs or aspire to the lifestyles of the global elite. Already now, the carrying capacity of many ecological assets are being compromised. Even the prevalent linear economic model is in itself inherently unstable. To continue business as usual is not an option. So how can we solve this equation?

Target 12:5 – Linear to Circular

“By 2030, substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse.”

By necessity, we have to change the way we think about the economy, and how we consume.

Linear Economy

Up until now, the prevalent economic model has been linear. A linear economy stays stable only if it is continuously growing, and in order to achieve that objective, policies and strategies that sustain consumption have been put in place. A key component of them is to encourage the spending of ever increasing amounts of money on goods and services; often goods and services that we do not even need and cannot afford. This is not only disastrous for our planet in the medium to long term, due to increased pressure on natural resources, and more polluting emissions from manufacturing processes and during the life cycle of the products, but also potentially disastrous in the short term for individuals. Consumption is now to a significant degree sustained by debt. We borrow money to continue consuming. Expansion of the linear economy through debt kept on without much concern until the 2008 global economic crisis, when the inherent instability of the debt driven linear economy became painfully obvious to many companies and individuals. Another key component is the fast flow of capital. Products in a linear economy are deliberately made to last for a short while, so that you need to buy new soon.

In the past century, costs for materials and energy have generally constantly decreased, while in the 21st century they are expected to constantly increase, when supply can no longer match the demand. The ongoing resource price paradigm shift, by necessity, will change priorities of companies and nations to increasingly manage existing resource stocks, since they provide future material security at costs invested in the past. “The resources of yesterday will become the goods of today, at the cost of yesterday,” to quote Walter Stahel, Director of the Product-Life Institute in Geneva, Switzerland, and one of the contrivers behind the circular economy concept.

In a circular economy, products are maintained and repaired, remanufactured or recycled, in the given order of priority. Metals can be recycled indefinitely, while other materials successively lose their value with each loop of recycling, and eventually have to be replenished by new feed stocks. Therefore, extractive industries and production of virgin raw materials cannot be completely eliminated, but significantly reduced. With some degree of generalization, for an average product, about three quarters of the energy is spent on extraction and raw material production; one third on the manufacturing. Consequently, a circular economy potentially comes with major reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. Furthermore, major savings of water and processing chemicals necessary for the raw material extraction or production, refining and manufacturing of products can also be achieved. Add to that a reduction in waste, as what we earlier considered to be waste is a resource to the circular economy. The economics behind the circular economy model is to maximize the value retention of materials or products throughout their life cycles, by extending their life spans, and this requires human resources to maintain, repair, remanufacture and recycle. A circular economy is, therefore, labour intensive and will generate new jobs locally, regionally and globally. Reforms that shift taxes from labour and wages to non-renewable materials and manufacturing will support the transformation of the economy into an increasingly circular.

Circular Economy

Unlike in a linear economic model, where cash flows are quick and focus on ever expanding markets, investments in a circular economy are more slow-moving and aim to secure our assets in the future. They include, of course, the productive capacity that allows us to provide goods and services, but must include development of durable, repairable and recyclable materials and products, as well as new clean technologies, to protect the ecological assets – the fundamentals of any economic model. In addition to that, in a circular economy investments focus more on humans, by creating labour-intensive enterprises retaining the value of the materials and products, which contributes to socially and environmentally more resilient societies. With this shift to new forms of enterprises, new forms of ownership can also emerge, where, for example, communities own their own value-retaining operations, with consequences for distribution of wealth. The conventional shareholder capitalism in the linear economic system sucks wealth out of the system and concentrates it to a few individuals, as consumers are constantly encouraged to discard and buy new products.

Ultimately we must also review our concept of what a “prosperous” life is. This may sound dramatic at first, but, in fact, is not so to most of us. What people in general wish from life is good health, education, social care, and a sense of leisure and recreation. Materials and products support these qualities, but the value is not in the materials or products themselves, rather in the functions provided by them. So why then do we need to chase novelties and trends, which makes us pre-maturely discard materials and products that are still functional and replace them with new ones? As mentioned, the circular economy is labour intensive. A linear economic model relocates people out of service-based sectors, to increase productivity in the manufacturing sector, while what most of us see as quality in life is provided from service-based sectors.

Target 12.4 — Sound Management of Chemicals and Waste

“By 2020, achieve the environmentally sound management of chemicals and all wastes throughout their life cycle, in accordance with agreed international frameworks, and significantly reduce their release to air, water and soil in order to minimize their adverse impacts on human health and the environment.”

Chemicals Essential in our Daily Lives, but Potentially Harmful

Chemicals are essential for development and welfare — we now use them in almost all aspects of our everyday lives. For example, processing chemicals support extractive processes, manufacturing and recycling operations, give functions to materials, are medicaments, and help us preserve food, among many things. However, chemicals must be managed in a sound way. This is, in many respects, not the case today. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), at least 1.6 million people die each year due to exposure of selected chemicals exposure, which potentially makes this total even higher considering global under-reporting from chemicals related exposure and deaths. The global production of chemicals is projected to double in the next ten years, according to the United Nations Environment (UN Environment). Many more will suffer from illnesses or die, and the degradation of the environment and biodiversity continue, unless serious efforts are urgently made to put in place sound management of chemicals.

Target 12.4, basically, reflects the overarching goal of the United Nations chemicals strategy, which is the Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM). The mandate of this strategy expires in 2020, and discussions on what the successor to SAICM post 2020 will look like are still ongoing. SAICM was created in recognition of the fact that the few legally binding multi-lateral environmental conventions in place for managing chemicals and toxic waste globally left some big gaps. Currently only 29 chemicals are banned or regulated at the global level, by the Stockholm and Minamata Conventions, but many more have hazardous properties among the tens of thousands of toxic chemicals in international trade. The original SAICM model chosen to address the gaps is fundamentally a voluntary regime with multi-stakeholder participation. Although a positive exercise and experience in many respects, 13 years after its launch, however, it is clear that SAICM has not delivered on its overarching goal: “sound management of chemicals throughout their life cycle so that by 2020, chemicals are produced and used in ways that minimize significant adverse impacts on the environment and human health”.

SAICM suffers from its voluntary nature with no obligations for the State stakeholders in the agreement to execute and monitor progress on activities outlined in the SAICM global plan of action, weak commitment from UN Environment and WHO (as they have no clear ownership over the regime), a chronic lack of funding, as funders expect to see value for the money in the form of systematic implementation of the targets in the global plan of action and regular progress reporting, which is also lacking.

In spite of this the international community now has an opportunity to address the shortcomings of SAICM post 2010. In this respect, a recent consultant report by Milieu offers useful advice. The consultants propose a hybrid model, with voluntary and legally binding elements for the successor to SAICM. One of the proposed legally binding elements address harmful chemicals in materials.

Towards Safe Circularity

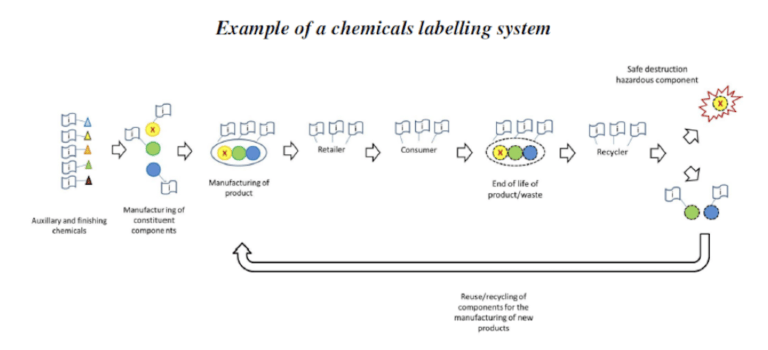

The presence of harmful chemicals in materials is an obstacle that hampers the full potential for a circular economy. With no mandatory transparency requirements for harmful chemicals in materials, indiscriminate reuse and recycling of materials may cause uncontrolled and widespread distribution of such chemicals. The European Union (EU) already works towards a clean circular economy by developing measures for an effective chemicals and waste legislative interface, and this thinking should also be adopted at the international level. Top priority to regulate are chemicals corresponding to what in the EU legislation is called Substances of Very High Concern (SVHC) — chemicals that are classified carcinogenic, mutagenic, toxic to reproduction, persistent to degradation, prone to accumulation in living organisms, and toxic, or of equivalent concern, such as affecting the regulation of the hormone systems in organisms.

If chemicals corresponding to SVHCs are banned, or if they cannot immediately be substituted with safer alternatives and are strictly regulated and coupled with mandatory transparency requirements, we at once unlock much more of the potential of the circular economy. Eventually, it will be necessary for manufactures of chemicals and manufacturers to provide full disclosure of the chemicals they use for manufacturing materials and products, since a chemical that is not considered to be harmful at the time it is used, may become so during the life cycle of the material and product in which it is. This would help us to track in which materials and products, including remanufactured products or products of recycled materials, that the chemical in question is in and limit its distribution and potential damages.

It is vital to address chemicals and waste together, especially at the global level, as they are highly intertwined, for example by the so called Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Convention synergy process. Furthermore, the economy nowadays is globalized, often with multi-national supply chains for materials and components of products. Certain harmful chemicals quickly gain widespread and uncontrolled distribution via the multi-national supply chain, and could rightfully be labelled “chemicals of global concern.” The majority of them are not regulated by international conventions.

Hence, regulatory actions in single countries to address “chemicals of global concern” in materials and products will be exceedingly costly, impractical, inefficient or insufficient, rather strong and well-coordinated global efforts will be necessary. We strongly believe that the successor to SAICM must contain a mechanism for global regulation of harmful chemicals that are not covered by existing conventions and have global distribution patterns in multi-national supply chains for materials and components of products (across the full life cycle), in order to protect a clean circular economy globally. Such a mechanism should include mandatory transparency for all harmful chemicals that cannot be immediately substituted. Key for securing a clean circular economy (other than a strong and well-aligned legislative chemicals and waste interface) are continuous efforts to substitute harmful chemicals with harmless or the least harmful chemical alternatives, or non-chemical alternatives. The responsibility falls on the industry to provide solutions.

Some two decades ago, the concept of “green chemistry” was launched. It strives for hazard reduction by designing least-toxic chemicals from renewable feedstocks, with minimal waste production and water and energy use in the manufacturing processes, recycling of auxiliary chemicals, such as solvents and catalysts, in the manufacturing, and reuse and recycling of chemical products. Efforts to encourage “green chemistry” must continue, for example by shifting the tax burden to chemical industries that do not operate according to these principles.

Several Targets to the Sustainable Development Goals Depend on SDG 12:4 and SDG 12:5

Circular economy is an important strategy in the work with the SDGs, but only if the SDG target 12:4 is first fulfilled. Fulfilment of the SDG targets 12:4 and 12:5 will help us progress towards achievement of a good number of the other targets of the SDGs, as outlined in the examples below:

- SDG 3.9 “By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination”.

A circular economy can result in both less emissions of pollutants by volume, and of less hazardous chemicals.

- SDG 6.3 “By 2030, improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimizing release of hazardous chemicals and materials, halving the proportion of untreated wastewater and substantially increasing recycling and safe reuse globally”.

A circular economy can result in both less emissions of pollutants by volume, and of less hazardous chemicals.

- SDG 6.6 “By 2020, protect and restore water-related ecosystems, including mountains, forests, wetlands, rivers, aquifers and lakes”.

A circular economy can result in both less emissions of pollutants by volume, and of less hazardous chemicals.

- SDG 7A ”By 2030, enhance international cooperation to facilitate access to clean energy research and technology, including renewable energy, energy efficiency and advanced and cleaner fossil-fuel technology, and promote investment in energy infrastructure and clean energy technology”.

Sound management of chemicals, in which “green chemistry” is a strategy, will be part of finding clean solutions to renewable energy with high energy efficiency, and less toxic waste at the end.

- SDG 8.4 “Improve progressively, through 2030, global resource efficiency in consumption and production and endeavour to decouple economic growth from environmental degradation, in accordance with the 10-year framework of programmes on sustainable consumption and production, with developed countries taking the lead”.

This is what a circular economy will help us with.

- SDG 8.5 “By 2030, achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value”.

This is what a circular economy will help us with. A circular economy is labour intensive and can create many new job opportunities for people with all levels of skills.

- SDG 8.8“Protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants, and those in precarious employment”.

A clean circular will help us with this. In many low and middle income countries, there are now informal recycling operations handling materials with unknown compositions of hazardous chemicals. By phasing out harmful chemicals from the material cycles in a clean circular economy, we will automatically also protect these informal economic sectors.

- SDG 9.4 “By 2030, upgrade infrastructure and retrofit industries to make them sustainable, with increased resource-use efficiency and greater adoption of clean and environmentally sound technologies and industrial processes, with all countries taking action in accordance with their respective capabilities”.

Sound management of chemicals, in which “green chemistry” is a strategy, will be part of finding clean technology solutions.

- SDG 10.1 “By 2030, progressively achieve and sustain income growth of the bottom 40 per cent of the population at a rate higher than the national average”.

A circular economy can potentially be part of a strategy for achieving that target. It can create job opportunities for people with all levels of skills.

- SDG 11.1 “By 2030, ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums”.

Sound management of chemicals, in which “green chemistry” is a strategy, will be part of creating materials for safe housing. Nowadays, many building materials, insulation materials, fillers, glues, paints and other components of houses contain hazardous materials.

- SDG 11.2 “By 2030, provide access to safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable transport systems for all, improving road safety, notably by expanding public transport, with special attention to the needs of those in vulnerable situations, women, children, persons with disabilities and older persons”

Sound management of chemicals, in which “green chemistry” is a strategy, will be part of creating sustainable transport systems, for example powered by renewable energy sources.

- SDG 11.3 “By 2030, enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanization and capacity for participatory, integrated and sustainable human settlement planning and management in all countries”.

A circular economy has the potential to employ more people in the transformation of the urban environment into sustainable. This includes aspects of waste management and reduced emissions to water and air.

- SDG 11.6 “By 2030, reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including by paying special attention to air quality and municipal and other waste management”.

This is what a circular economy will help us with.

- SDG 14.1 “By 2025, prevent and significantly reduce marine pollution of all kinds, in particular from land-based activities, including marine debris and nutrient pollution”.

A circular economy can result in both less emissions of pollutants by volume, and of less hazardous chemicals. It will also reduce the influx of waste to oceans.

- SDG 14.3 “Minimize and address the impacts of ocean acidification, including through enhanced scientific cooperation at all levels”.

A circular economy will decease atmospheric emissions of acidifying agents, such as carbon dioxide, and sulphur and nitrogen oxides.

- SDG 15.5 “Take urgent and significant action to reduce the degradation of natural habitats, halt the loss of biodiversity and, by 2020, protect and prevent the extinction of threatened species”

A circular economy can result in both less emissions of pollutants by volume, and of less hazardous chemicals. This will help nus protect ecosystems with their associated biodiversity.

- SDG 17.3 “Enhance global macroeconomic stability, including through policy coordination and policy coherence”.

A circular economy has the potential to be inherently more stable than a consumption-driven linear economy, which will improve macroeconomic stability, and the need for global harmonization of chemical regulation will strengthen policy coordination and coherence, to the benefit of companies that in all countries will get more predictability and a more even playing field in the global market. ´

- SDG 17.4 “Enhance policy coherence for sustainable development”.

A circular economy has the need for global harmonization of chemical regulation, and hence will strengthen policy coordination and coherence, to the benefit of sustainable development, as well as of companies that in all countries will get more predictability and a more even playing field in the global market.

For more information: rico@groundwork.org.za