Different doctors don’t treat the same disease the same way. Often, these inconsistencies in care are slight, without major effects on someone’s recovery. Sometimes, however, these differences are significant. If two hospitals in the same town have very different results when treating the exact same disease, how well someone heals may depend on whether their ambulance turns left or turns right. Even across small spaces, there can be big gaps, leading to variations in medical care that affect patients’ lives.

These differences in healthcare practices are not a new problem. In 1938, after decades of data collection by the British government, Dr. J. Allison Glover published an astonishing study that found drastically different rates of diagnosis and treatment for certain diseases among children in the United Kingdom. And while it would be easy to argue that certain illness would disproportionately affect certain communities, Glover came to a different conclusion: some, of the disparities in healthcare are the result of variation in how doctors practice medicine, leading to significant and haphazard variations in the treatment and diagnosis, even between relatively similar communities.

Dr. Glover was the first to describe a phenomenon that we now refer to as small-area variation. Simply put, even across a small space, where the demographics don’t differ, there can be enormous differences in how health care is practiced. In his study, called “The Incidence of Tonsillectomy in School Children,” Glover showed that the rate of children getting their tonsils surgically removed was ten times higher in Oxford than in Cambridge, two very similar communities. Both are wealthy, educated suburbs of London, roughly equal in size, nestled along a river, and home to a world-class university with a top-notch medical school run by eminent physicians. Why would there be ten times as many tonsil surgeries in Oxford? It’s possible that children from Oxford were ten-times more prone to tonsil disease than children in Cambridge, but it’s more likely that doctors at Oxford were just ten times more likely to recommend a surgery for it.

It’s possible that children from Oxford were ten-times more prone to tonsil disease than children in Cambridge, but it’s more likely that doctors at Oxford were just ten times more likely to recommend a surgery for it.

Forty-five years later, this problem was as alive as ever. In 1973, two American researchers, Drs. John Wennberg and Alan Gittelson, published a now famous study comparing healthcare across the state of Vermont. In many ways, Vermont was the perfect place to test whether small area variation was a real problem. The state consisted of many small to mid-sized towns, each of which was fairly similar by most major demographic and socioeconomic metrics. These were Oxford/Cambridge comparisons. And, even after another half century of medical research and progress, Wennberg and Gittelson found the same results that Glover had: the rates of tonsil surgery were ten times higher in some Vermont towns than in others, even if the two towns were very similar.

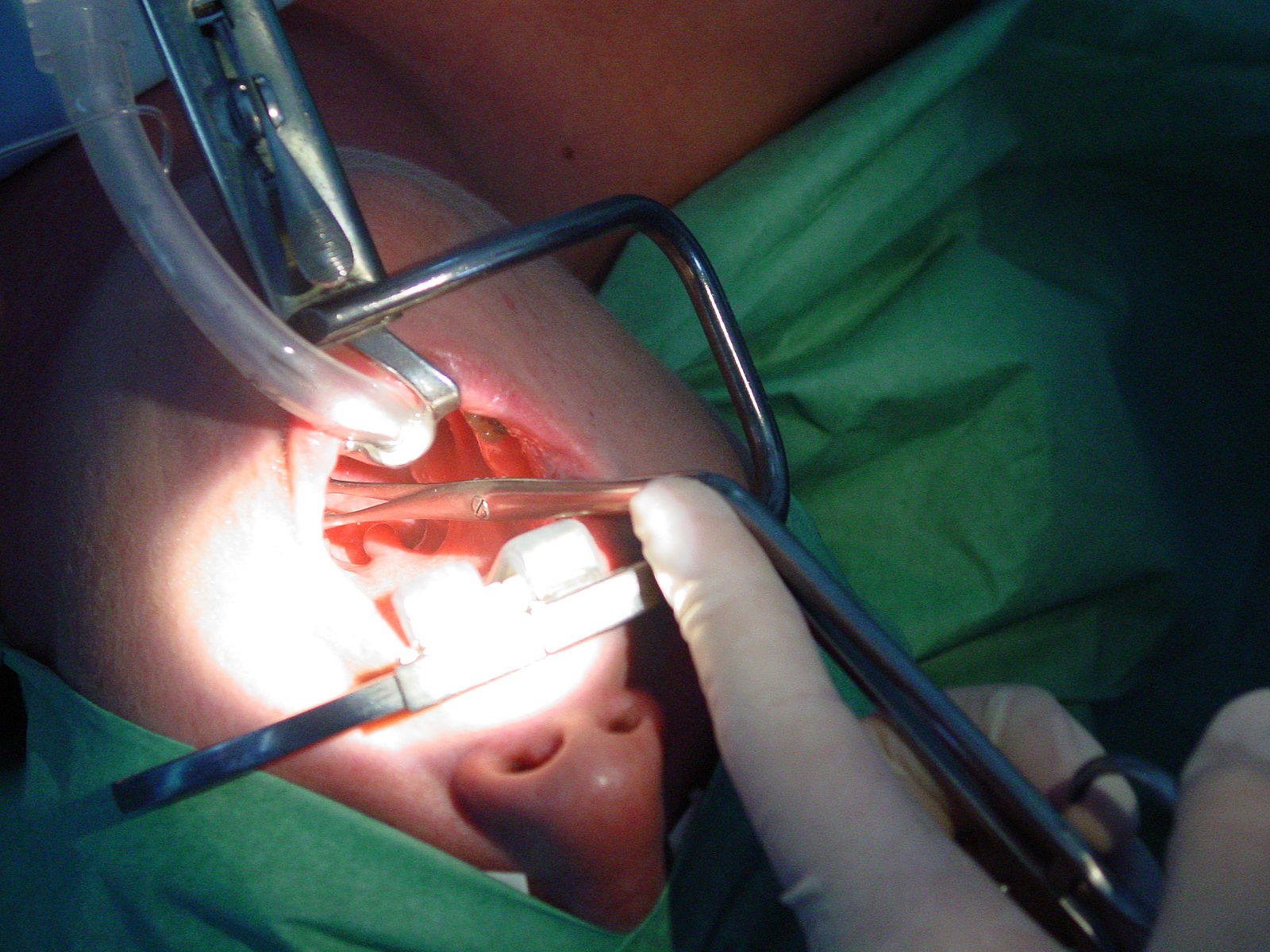

Photo: Tonsillectomy surgery.The rates of tonsil surgery were ten times higher in some Vermont towns than in others, even if the two towns were very similar citing small-area variation among practices. Photo credit: WikiMedia Commons

Now, healthcare probably should not be cookie-cutter. The same therapy does not always work equally well for everyone. That said, we expect some degree of consistency in how healthcare is delivered. And yet, Oxford and Cambridge, both of which have renowned medical faculty, each treated the same disease differently. Were the faculty at Oxford performing unnecessary surgeries? Were the doctors of Cambridge negligently letting their patients languish? And if there is this much variation in treatment for other diseases as well, how many tens of thousands of people are being misdiagnosed or inappropriately treated by their physicians?

As I continue my own surgical training, I have to consider whether I am learning to provide the best care I am capable of offering. But what are neurosurgeons at other institutions learning that I am not? What are they learning to do differently? Is their method better than mine? How do I even find answers to these questions?

Related article: “FLOSSING, HEART DISEASE, AND THE HUMBLING HISTORY OF MEDICAL SCIENCE”

One devastatingly common disease that neurosurgeons treat is intracerebral hemorrhage, or ICH, which is when bleeding occurs inside the skull. In Chicago, where I am training, there are five major academic medical centers that provide specialty care for diseases like ICH: the medical centers of Loyola University, Rush University, Northwestern University, the University of Chicago, and the University of Illinois. And, according to a study published earlier this month, led by Dr. Andrew Naidech, there are measurable differences in how ICH is treated at these different institutions.

IN THE PHOTO: A CT scan of the brain showing intracranial hemorrhage (ICH). The arrows point to the bleeding inside the brain. Would small-area variation cause doctors out of the 5 academic medical centers in Chicago to all perform ICH surgery differently? Photo credit: WikiMedia Commons

Any injury to the brain can cause seizures, and ICH is no exception. For a long time, it was standard for patients with brain bleeding to take anti-seizure medications, but it wasn’t clear which anti-seizure drug worked best for ICH. Then, in 2009, a study showed that people taking one common seizure medication do not recover from their injuries as well as people taking another. In response to this study, many doctors stopped prescribing the medication that was linked to poor recovery, and started prescribing the medication that was linked to good recovery. However, Dr. Naidech’s study showed that patients at each major medical center in Chicago were treated very differently. Patients at one hospital were almost five times more likely to get the drug linked to good recovery than patients at another. Each medical center is staffed with experts distinguished in their fields, yet patients at one of them receive markedly different treatment than patients at another.

Patients at each major medical center in Chicago were treated very differently. Patients at one hospital were almost five times more likely to get the drug linked to good recovery than patients at another.

One problem with this kind of analysis, however, is that it can be hard to tell if you’re comparing apples and oranges. Some of the Chicago medical centers in Dr. Naidech’s study are only a few miles from one another. Chicago, my home, is a city divided – it is one of the most segregated city in America, with certain neighborhoods plagued by poverty and violence, while other areas thrive only a short distance away. What can we make of the differences in the care offered at each? Do underlying socioeconomic circumstances produce a rift in care? Or do the diverging opinions of doctors lead to inconsistencies between practices?

Sometimes, it can be very hard to tell. Giving the recommended medication should be expected. Often, however, there is no one recommended pill, so there is no clear right answer. One thing that is clear, however, is that variations in healthcare are real, and can affect people’s lives. The solution isn’t just to do the right thing, but to do the right thing consistently, and to narrow the big gap between good care and great care.

Recommended reading: “HOW TELEMEDICINE IS TRANSFORMING HEALTHCARE”