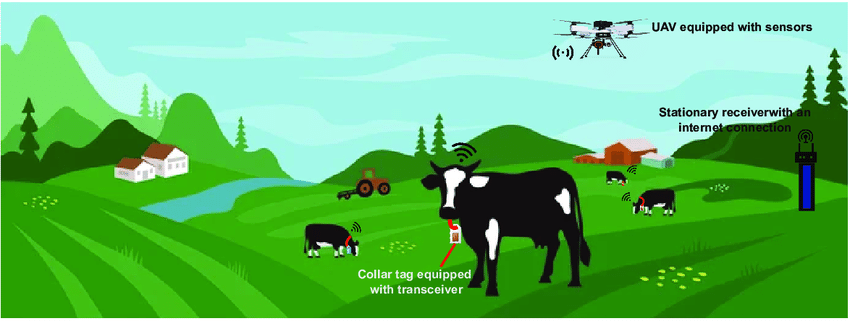

For the past few years, unmanned aerial vehicles (also known as UAVs or “drones”) have slowly but surely become part of the public consciousness. From their controversial use in war to the buzz generated by companies like Amazon, drones have departed from the realm of science fiction and firmly entered the realm of scientific reality.

One previously untouched area of interest that drones are now starting to get involved in is air cargo. For urban city-dwellers, getting supplies and products is pretty straightforward; freighter planes takeoff and land from the same airports as regular passengers. For those who live in rural or isolated communities however, getting supplies can be much trickier due to low population densities. As a result, drones, which by their nature don’t need humans to man them, offer a lot of promise and potential in making cargo deliveries easier and more direct for these populations.

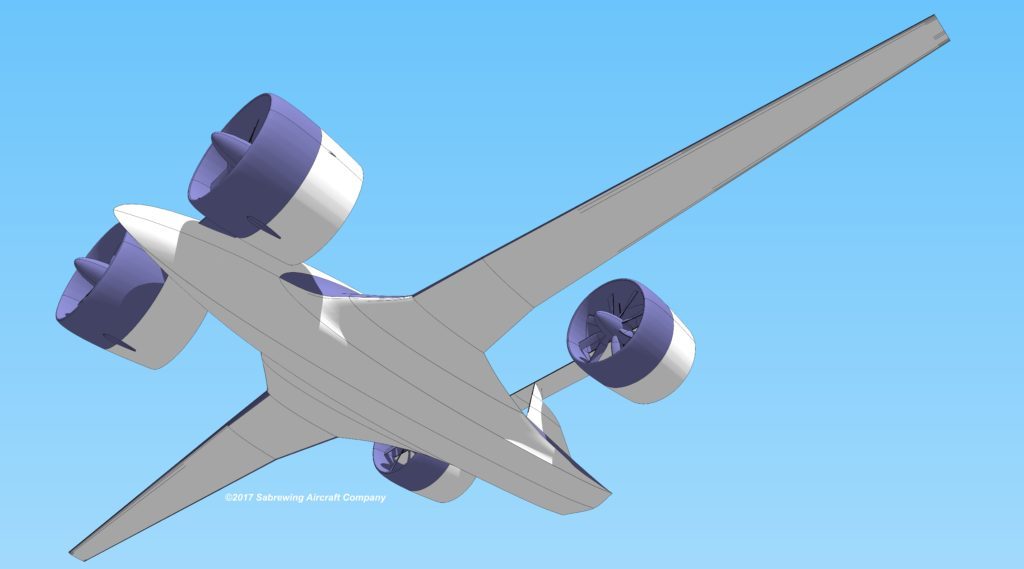

That value proposition was what motivated Ed De Reyes to co-found the Sabrewing Aircraft Company. The company, which has developed a UAV capable of carrying large loads of cargo over long distances, is also putting its name out there as part of the Pacific Drone Challenge, an international contest to see who can develop a drone capable of flying unmanned and nonstop from Japan to California. I chatted with Ed to learn more about Sabrewing’s beginnings, the Pacific Drone Challenge, and his company’s entrant in the competition, the DRACO-2.

How did the Sabrewing Aircraft Company originally start?

Ed De Reyes: The company itself first started when I met our Chief Technology Officer Oliver Garrow in Oshkosh back in 2014. We kept in contact, and I had seen some of his designs and was very interested in some of the stuff that he had done. I had had a design running around in the back of my head for years, a regional air cargo drone that could lift about a ton of capacity and was very fuel-efficient. I had spent several years doing basic paper calculations to figure out if there was some way this could be done before discussing them with Oliver. He had several designs that he put forth and worked on getting to fly. Finally, he and I collaborated on a final design, which is now the DRACO.

In the Photo: Rendering of Sabrewing Aircraft. Photo Credit: Sabrewing Aircraft Company.

In the Photo: Rendering of Sabrewing Aircraft. Photo Credit: Sabrewing Aircraft Company.

Sabrewing is competing in the Pacific Drone Challenge, could you talk more about it and why you decided to enter the competition?

EDR: The challenge is to fly from Japan to the United States unmanned, unrefueled, and nonstop. The drone space now is kind of what the manned aircraft space was in the late 1920s. They were developing very durable engines, cargo capacity, the ability to fly long distances, etc. There were a lot of advances made during that time, before eventually reaching a stage of maturity where it was possible to fly transoceanic. We’re in a similar state today. That was manned aircraft, now it’s unmanned aircraft, but even now the technology is there to fly transoceanic. At this point it’s really about being able to come up with a method of flying efficiently from one point to another, hence our aircraft.

iRobotics was the original company in Japan who first came up with the first idea and said, “we want to fly transoceanic from Japan to the United States, and anybody that wants to challenge us or join us is welcome.” That was really the birth of the Pacific Drone Challenge, and we were the first company to step up and say, “yes, we can do it, we want to do it, and we will do it.” The challenge has grown from there, and the rules have become more formalized, including things like flying nonstop, unmanned flying, no landing on a boat or rock or balloon, etc. But other than no rockets and no balloons there really aren’t any other restrictions in terms of power or propulsion or anything else.

We’ve had people that are interested, and there’s someone who’s currently very interested in picking up and running with the Pacific Drone Challenge in terms of sponsorship to make it a more official “race”. As of right now there are two official entries, iRobotics in Japan and Sabrewing Aircraft, but there are other people interested, including one party from Australia, another from New Zealand, a third from Ukraine, and a fourth from India.

In the Photo: A Ed De Reyes, Oliver Garrow and a rendering of Sabrewing Aircraft. Photo Credit: Sabrewing Aircraft Company.

RELATED ARTICLES:

![]() HopFlyt eVTOL: an Interview with Rob Winston

HopFlyt eVTOL: an Interview with Rob Winston

by Alessandro du Bessé

![]() Ampaire electric planes: Interview with Kevin Noertker

Ampaire electric planes: Interview with Kevin Noertker

by Alessandro du Bessé

![]() VerdeGo Aero VTOL: An interview with Eric Bartsch

VerdeGo Aero VTOL: An interview with Eric Bartsch

by Alessandro du Bessé

It’s true that the technology that we have today was once taken for granted, so it’s interesting to see that process happening again.

EDR: When the challenge first came up, that’s the thing that popped into my head. With UAVs especially, the technology is there, but a lot of it is off the shelf. I’ve had people tell me specifically that there’s no way our aircraft is going to make the 4,500-5,000 mile trip, and I keep telling them that there are aircraft that have done that, like the Global Hawks that are flown from the United States to Australia. But that’s a military aircraft, meant specifically for the military, and as a civilian I couldn’t buy one and convert it into a cargo carrier. That’s really the difference, we’re building something that is really meant for someone like a Japan Airlines to load up with cargo and send out to Hokkaido or to very remote villages in Alaska.

Sabrewing’s entry into the competition is the DRACO-2, how does it work and why do you believe it’s a contender for the challenge?

EDR: Two things, we built in the ability to fly long distance, and also we built in the ability to carry heavy loads. Our model is a gas-electric hybrid, which uses 15-20 gallons per hour of fuel burned, compared to a Cessna Caravan that burns roughly 90 gallons an hour. That’s a very large disparity between the two, and to be able to carry as much as a Caravan is really the big differentiator.

The DRACO-2 is more focused on flying long distance because it’s purpose-built for the Pacific Coast Challenge, but it’s a 65% to scale version of our full-sized vehicle, and both use electric motors for propulsion. The DRACO-2 is purpose-built strictly for cruising at a high speed and altitude, but the full-size model, what we’re calling the Wyvern, will be able to take off in a very short distance and go to altitude. As soon as it burns off the fuel it’ll have the capability to land vertically, drop off its cargo, and then take off again vertically and return home, or go on to a second location.

In the Photo: Rendering of the Sabrewing model. Photo Credit: Sabrewing Aircraft Company.

In the Photo: Rendering of the Sabrewing model. Photo Credit: Sabrewing Aircraft Company.

What do you see as the future of Sabrewing?

EDR: It’s always hard to look 10 years into the future, but I think that within the next 5 years we’re going to see unmanned cargo become much more ubiquitous, and it’ll be adopted in places like Alaska where a lot of small, disparate villages have air cargo as their only form of supply. We’ll also see it adopted in places like western Canada and other very rural areas where the air lanes are sparsely populated but the need for air cargo is growing by leaps and bounds.

As for us in 10 years…I don’t know. As I’ve told my investors, it’s a board decision, not an Ed De Reyes decision as CEO. But we’re positioned to be either an M&A target or an IPO. At this point, if things go according to plan, we don’t think we’ll even need a Series A to reach initial production. It’s not out of the question, but it doesn’t look like it’s a necessity for us. The thought is to build a healthy company and build a company that has a very good financial footing.

We’re really one of the only companies in this space too. Our only competitors are not in the same weight class. There’s the Natilus, but they’re focused on tens to hundreds of thousands of pounds of cargo load, with conventional takeoff and landing, basically taking the place of the 747 freighter and MD11 freighter. Then there is the Elroy, but they’re looking at 150 pounds in a 300 mile range. We’re the only ones looking at replacing current aircraft in one role, specifically air cargo.

That’s not to say that the Caravan or the Quest wouldn’t have a market though; they’d still have a market to transport people. We steered clear of having people on our aircraft simply because of regulations. The FAA has really come along and is more amenable to working with companies, but I still think that the human factor is still unknown territory. While Uber and everybody else want to fly people, I think that’s going to be a very, very difficult sell still because of the fact that there’s nobody in the pilot seat. Cargo’s not like that though. If you lose grandma’s china that’s one thing, but if you lose grandma that’s a whole other story.