We, humans, are problem-solvers. As soon as a problem appears in our mental space, our brains immediately start whirring, looking for a solution. We’re filled with a sense of accomplishment when we find a solution that “fits”. The flip-side of that is that we find it depressing to contemplate a seemingly irresolvable issue. It’s a common occurrence for our minds to shut down when we encounter words summarizing gargantuan problems such as poverty, world hunger, nuclear threat, immigration. That is why it helps to speak of restoring planetary health instead, a friendlier term – let’s see how it works.

Consider climate change, it is perhaps the most all-encompassing and daunting issues of all. The underlying causes are so complex and inter-related that they are too vast for even the most informed and intelligent among us. Mother Nature is endlessly more intelligent and interconnected than we humans are. We as a race seem to be in denial over what we are doing to the planet which sustains us. When we have the courage to look at reality, we see that we pretend that finite resources are infinite, we pollute the air we breathe, contaminate the water we drink, pave over the soil in which we grow our food. We are the only species intelligent enough to devise ways to speed our extinction.

CREDIT: Habitat 3

Dealing with environmental despair

Anyone who follows ecological matters has to reckon sooner or later with environmental despair. The graphs that spike into uncharted territory in terms of gas emissions, ocean acidification, deforestation and arctic thawing grind combined with images of famished polar bears, now extinct rhinos, vast swaths of plastic in the open ocean and dying coral reefs grind into our psyches. On top of this, we have many benighted politicians around the globe who either ignore environmental matters or, even worse, purposely undermine any legislative progress that has been made.

A good summary for our reasons for despair can be found in the article entitled “I Felt Despair About Climate Change—Until a Brush With Death Changed My Mind” published on Slate in March 2018. It was written by Alison Spodek Keimowitz, assistant professor at Vassar College with a focus on environmental chemistry and pollution. She’s a scientist and lays the situation out in a bleak sentence: “The overall trajectory of life on Earth is well-understood: We are in the midst of Earth’s sixth mass extinction, and the odds of human civilisation reaching the 22nd century are often estimated at no better than 50/50.”

This is the sort of sentence that stops me in my tracks. I find it almost physically painful and I find myself entering into my own dance with denial. It may be the truth and yet I find it psychologically counter-productive. It risks paralysing me, like a deer frozen in the headlights.

I’m not willing to resign myself and believe that beyond any doubt humanity is condemned to unimaginable pain and potential destruction. As far as I’m concerned, we must find a way. We must work tirelessly to promote and enact solutions.

Breaking issues down into more manageable pieces

Many of us have been taught that when a task before us is overwhelming, an effective strategy is to break a problem into smaller pieces. This renders a complex project more manageable. It simplifies it and allows our minds to focus on a given aspect, rather than spinning out of control in a frustrating attempt to solve an impossibly complex issue all at once. We just hone in on a smaller part that we could effectively contribute to.

This is one of the many reasons why I find the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to be the single most encouraging and important environmental initiatives ever launched. They begin with an overarching, comprehensive vision which then has been broken down into 17 goals and related sub-goals. Individually the goals address basically every issue that worries us about our world: ending poverty and hunger, promoting quality education, sanitation, good health and gender equality, promoting peace and justice, and generally finding ways to take care of our fragile planet and its finite resources upon which we depend.

IN THE PHOTO: Jaipur, India – clean drinking water is a colossal challenge. CREDIT: Sarah Marder

Every single SDG is of capital importance and they are interrelated. We must work towards achieving all of them to transform the world’s development paradigm into a sustainable model for all. That said, I feel that SDG 11 regarding sustainable communities is arguably the single most important of all the goals. To be more specific, SDG 11 states the following goal: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.

When you examine the components of that goal, it becomes clear that it aims at the all-around well-being of our communities and asks us to mitigate the impact that we humans are having on the Earth. It draws an image of places that are not only environmentally sustainable but also geared towards social justice and peaceful living for all. In just ten words the goals convey the interdependent relationship between people and place, which is a universal issue and it requires holistic thinking and solutions.

Fighting climate change and restoring planetary health begins in the city

The importance of cities in the climate change equation cannot be overestimated. As we know, more than half of the world’s population lives in the urban environment. By 2030 that proportion will rise to 60 percent. This human concentration naturally corresponds to a concentration in production, consumption and waste. The world’s cities occupy roughly 2 percent of the Earth’s land but account for approximately 60 percent of energy consumption and 70 percent of carbon emissions.

Moreover, world population is forecast to climb to 11 billion by the end of this century and urbanisation is expected to continue at a blistering pace, simultaneously exerting pressure on fresh water supplies, sewage, the living environment, and public health.

As I write this, I have just returned from a trip to Jaipur, a world heritage city in the State of Rajasthan in India. While in India, the universality and urgency of SDG 11 and its targets struck me in a particularly powerful way. The trip was a poignant and potent reminder of the challenges we are facing that may seem abstract when we live in comfort, surrounded by few visible signs of environmental degradation, economic poverty and human struggle.

IN THE PHOTO: Cities are the arenas where many climate challenges converge. CREDIT: Sarah Marder

Many important bodies have recognised the centrality of the city and are laser-focused on finding and promoting solutions to these vexing issues. One of these is the World Urban Forum, a non-legislative technical forum convened by the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) held since 2002. It recently convened in Kuala Lumpur and resulted in declared goals of localising and scaling up the implementation of the New Urban Agenda. Clearly, much work remains to be done but the fact that practitioners and policymakers from around the world converge and share ideas is an important part of the process.

A concentration of problems can also allow a concentration of solutions

Without being gullible or entering into downright denial, we can make a conscious effort to focus on what gives us hope. In the case of cities, there is a flip-side to the concentration of consumption, emissions and waste; there is also a concentration of people, intelligence and social capital. Cities are high-density human settlements that, if organised in a wise way, can create technological innovation and can achieve efficiency gains to reduce consumption of energy and other resources. In other words, rather than looking at cities as the places creating the problems, we can look at them as incubators and vital areas that can generate solutions.

Groups such as C40 cities say that “ending climate change begins in the city”, showing concrete examples of how municipal governments are taking responsibility for dealing with environmental issues, rather than waiting for national level governments to take the initiative. The Mayors of the cities involved in C40 rightfully see their urban areas as an empowered entity where issues can be identified and solutions can be sought and enacted.

“No matter what decision is made by the White House, cities are honouring their responsibilities to implement the Paris Agreement,” says Anne Hidalgo, Mayor of Paris and C40 Chair. She adds, “there is no alternative for the future of the planet.” While many of us would agree with these words, in theory, it is crucial that cities find ways to turn these words into reality. Below are some of my observations about a few of the sub-goals of SDG 11.

By 2030, reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including by paying attention to air quality and municipal and other waste management

Living in Milan, Italy, one of the European cities with the most chronic air pollution problems, I have seen how intractable these problems can be and how difficult it is to get both politicians and citizens to embrace courageous measures that would be necessary to improve air quality. In the case of Milan, politicians point fingers at the geographic conditions which cause smog to collect in this low-lying area surrounded by the Alps to the north, trapping toxic air here, leaving all of us breathing unhealthy air, resulting in increased chronic respiratory problems among the population and even reducing life expectancy.

IN THE PHOTO: Jaipur, India – a hand-painted wall welcoming visitors to this UNESCO heritage city. CREDIT: Sarah Marder

Citizens tend to be resigned to the situation, unthinkingly repeating the clichéd phrase that this is part of living in a city and if you want to breathe good air, you should go to the mountains on the weekends and for vacation. This is obsolete thinking and it certainly doesn’t factor in the importance of air to our health.

To achieve good air quality would mean that countless environmental battles will have been won, so it’s a fine proxy indicator of how well Milan is doing to move towards becoming a sustainable and healthy city. To have fewer contaminants in the air we need to increase access to public transportation (a sub-goal of SDG 11) while reducing car dependence, we need to plant more trees and increase green and blue spaces, we need to convert buildings to heating systems that don’t pollute.

All of this requires not only vision and courage from the municipal government but also pressure, awareness-raising and collaboration from below. For instance, the city is building more cycling infrastructure and, concurrently, groups in civil society are carrying out campaigns to promote Milan as a city that is good for cycling, since it is small, dense and flat. When these top-down and bottom-up movements collaborate and converge, they can become powerful to the point of becoming paradigm changing, one piece of the puzzle at a time.

An example of this is China, as recently reported in the New York Times article Four Years After Declaring War on Pollution, China Is Winning, telling of how the government declared war on pollution as it had previously declared war on poverty and is achieving significant reductions in particles in some urban areas, resulting in lengthened life expectancy. News of this sort was unthinkable even a few years ago. Imagine a proliferation of this sort of attitude in cities and countries around the world.

IN THE PHOTO: Jaipur, India – a subway system is under construction, to alleviate some of the city’s traffic problems. CREDIT: Sarah Marder

Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage

Switching gears, another sub-goal of SDG 11 which I care deeply about encourages us to take care of the world’s cultural and natural heritage. To some, this might seem nice-to-have but not particularly important. Perhaps because I’ve spent my whole adult life living in Italy, surrounded by awe-inspiring landscapes and places of antiquity, I see this topic as being of vital significance and deeply interrelated with other goals, no matter where we live. For instance, if you live in the United States, you might realise how deeply you care about our National Parks and how they contribute to our well-being, even on an emotional level. For many of us, they represent some of the more appealing aspects of our country’s character.

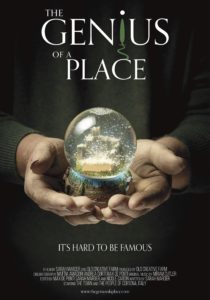

I believe we have a symbiotic relationship between ourselves and our places. I explored this relationship in the documentary The Genius of a Place, filmed in Cortona, the ancient hill town in Tuscany made famous by book then movie “Under the Tuscan Sun”. During our five years of filming in Cortona, which was an economic backwater before being launched to fame, we saw how the community tended instinctively to make a decision based upon commercial interests only to realise afterwards that they risked collectively selling the body and soul of their place of beauty. While the unexpected economic growth was welcome in many ways, they realised that they were losing other valuable aspects, potentially degrading the environment and community and lowering their quality of life that they had inherited from their forefathers.

IN THE PHOTO: Movie poster CREDIT: Paolo Volonté

While we were making the film, I came to see the fragility of places in the modern world. I felt that Cortona was a canary in a coal mine. If even Cortona could succumb to the forces of globalisation, surely every place on the planet was at risk. There were moments when I felt that we were ruining the planet, one place at a time.

Luckily, my internal pendulum swung away from those moments of despair and moved back towards hope. I became attracted to holistic thinking about place and planet. Influenced by David Suzuki, I began to see that we needed to reclaim our place in nature and what he calls “The Sacred Balance”. As I share in the video “We Need a Healthy Earth”, I began to see places through this lens. I began to see the link between our inside and outside world. As Kaid Benfield writes in People Habitat, “there is no sustainability without places that help limit environmental impacts while also nourishing the human spirit.”

Along the same lines, Mahatma Gandhi said: “Earth provides enough to satisfy every man’s needs, but not every man’s greed.” He also famously exhorted us to “be the change we want to see.”

Thus, the same way we might be ruining the world one place at a time, we can also learn to take care of it one place at a time. We humans may be problem solvers yet it’s counterproductive for us to be overwhelmed by planetary problems.

We’re better served to whittle down the scope of our concerns. We can realise that our well-being is intimately connected to every aspect of our specific surroundings. This is true whether we live in the city, the suburbs or the countryside. No matter where we live, Nature is our lifelong mother, providing the sun that warms us, the water we drink, the air we breathe, the food we eat. We need a healthy earth.

IN THE PHOTO: Sarah Marder interviewing Abbas Kiarostami for THE GENIUS OF A PLACE CREDIT: Antonio Carloni

If we’re city dwellers, we can contribute to efforts to bring more Nature into our city and stave off the expansion of our cities into Nature. Every single act that restores planetary health is of utmost importance. Collectively, we can learn to take care of this lovely and bountiful yet fragile planet that we inhabit. We each have a role to play. And if we’re wise, we’ll relish the opportunity.

Editors Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com

Featured image credit: Sarah Marder