Once again, European politicians disappoint, showing that they are not able to call a spade a spade and prefer to resort to the “safety” of bland language to make everyone happy. Last Friday, we learned that the EU Commission had agreed to change the name of its European defence plan. In response to complaints from Italy’s Giorgia Meloni and Spain’s Pedro Sanchez, von der Leyen’s original strong name for it, ReArm Europe was downgraded to “Readiness 2030.” The two politicians feared that the name would be misunderstood by European citizens, causing a backlash.

Moreover, the core of the EU plan would be given the even blander name “SAFE.” This is a €150 billion fund made available for EU member states in low-interest loans for purchasing advanced weaponry — with the proviso that at least 65% of the funds be used for “buying European.” And that, as I will show in this article, is precisely what could make a big difference in terms of impact on the economy.

In case you wondered about that date in the new name, 2030 refers to the year by which Russia is expected to have the military capability to effectively launch an attack against any EU or NATO member state. This is a little strange insofar as most European citizens probably had no idea that this Russian capability was still five years away into the future. I, for one, thought that Russia already had that “capability” — whether it could succeed is another question. It’s been hammering Ukraine, a much smaller country, for three long, tragic years, yet it still hasn’t won the war, far from it.

Indeed, for most Europeans, it’s perfectly clear why we need to “re-arm” or get “ready by 2030” (whatever you want to call it): The triggering event is not something that could happen in 2030. It’s something that has already happened as soon as Trump arrived at the White House. In just two months, with a tornado of executive orders, Trump has demolished the international order in place since World War II and turned his country into a rogue state.

Right now, here is where we are: Trump sees Europe as a commercial adversary and insists that it should spend its fair share on military expenditures. And Europe, in this case, is complying, and as I will show later down, it is in its best interest to do so.

What is in the €800 billion EU Commission’s European defence plan

Ursula von der Leyen, the head of the EU Commission, doesn’t mince her words: “Europe must prepare for war to secure peace,” she told the Royal Danish Military Academy last week:

In this historic address, von der Leyen outlined the “Readiness 2030” roadmap, aiming for a robust European defense posture by 2030, with increased defense spending, joint procurement initiatives, and strengthened support for Ukraine. She stressed the importance of a united and prepared Europe to deter aggression and maintain sovereignty.

A key feature of the plan is her proposed targeted relaxation of EU fiscal rules. Meant to assuage fiscal fears over the inevitable debt-building that increasing military spending entails, it makes it easier to rearm (or “get ready by 20230”). The expectation is that SAFE will have a stimulating effect and that it will be possible to mobilise up to €650 billion for a total of €800 billion over the next five years (until 2030).

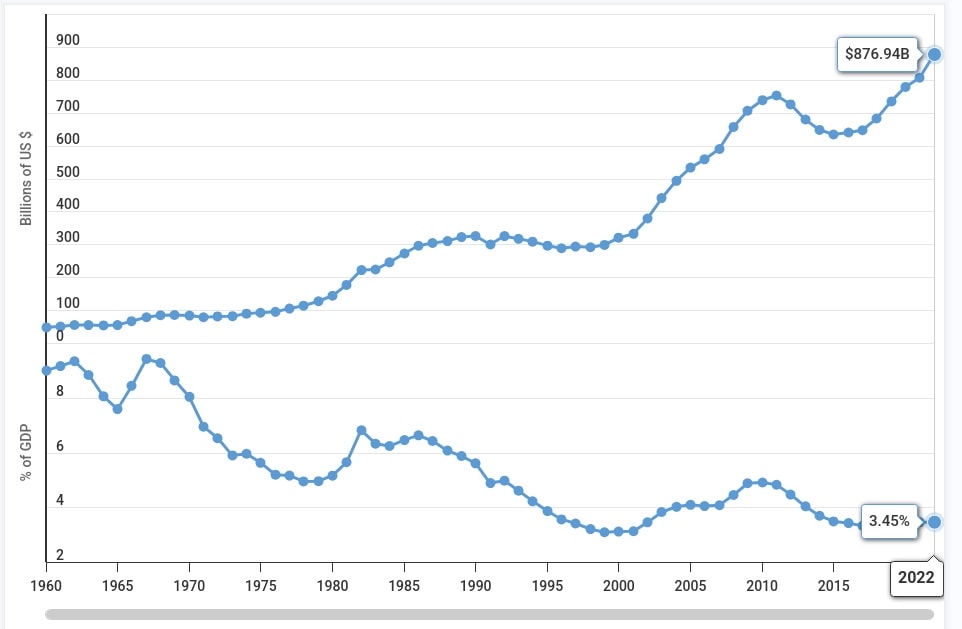

That sounds like a lot — but it isn’t. Consider that the US annual military spending has been regularly higher than that and is still trending upward: in 2022, it was $876.94B, an 8.77% increase from 2021. That’s the figure for one year, not five years as per EU Commission plans.

But the good news is that the EU Commission is not alone. Now we have Germany. With the new chancellor, Friedrich Merz, arriving on the scene, things have changed radically. On election night, he announced that establishing a European defence capability was his “absolute priority,” that with Trump in charge, we were “five minutes from midnight.”

Germany’s new military spending plan: Almost unlimited defence capability

Germany is poised to become once again a leader in Europe, paired with France as it had been in the past. At least until (former German Chancellor) Angela Merkel broke that partnership, no doubt one of Merkel’s major errors. Putting on pause the historic German-French collaboration, she paralyzed a major force that had been driving Europe forward.

Last Friday, a day after the European Union’s plan was agreed upon, the upper house of the German parliament gave the green light to an almost unlimited increase in defense spending. This involves lifting the “debt brake,” a constitutional rule that has limited Germany’s borrowing. Spending on defense and security, including aid to Ukraine, will be exempt from the national debt rules for spending above 1% of GDP.

The plan includes significant investments in Germany’s military capabilities. It also addresses the need to modernize Germany’s infrastructure (railways, airports, etc.), and a 500 billion euro infrastructure fund is part of the package. Funding has even been allocated for climate-related spending.

It sounds like a lot, but not all experts agree that it’s going to be enough to turn Germany’s defence capacity around and make it independent of US support.

For example, Marina Miron, a military analyst at King’s College London, is pessimistic and told the German media, DW News, that all this requires time to give results. She argues that modern warfare is reliant on advanced digital software that only the US possesses, that a country like Germany, unlike France, does not have nuclear power or an equally developed military industry, and that for some time yet, it will have to rely on American military support.

Other countries, however, are more realistic and worry that Trump could block access to software updates, components and maintenance should one politically disagree with him: This certainly puts a dark shadow on the famous F-35, the most advanced military planes of their kind, real “computers with wings.”

Already Canada, threatened with annexation by Trump, is considering alternatives to the F-35 and Portugal has already made a first step in that direction. Countries like Italy, with a decades-long addictive habit of buying American, will also need to consider breaking it.

Why “Buy European” is key for drawing maximum benefit from defence spending

The central question is: What is the real impact of defence spending on the economy, good or bad?

Right-wing politicians like Italy’s leader, Giorgia Meloni, argue it is bad news for the national debt. But they’re not just worried about increasing the debt: What they really want to see is “less Europe” and a return to the 1950s when Charles de Gaulle famously called for a “Europe of independent states.”

But history tells us that increased military spending is actually good news for the economy. Every EU member should take advantage of the EU Commission plan. Not to do so would be a serious mistake: A lost opportunity to strengthen the economy, and even make it more resilient and able to face the shock wave that will inevitably come in the near future when Trump is done crashing the US economy with his trade wars.

Because, as Pascal Lamy, former WTO Director General (until 2013) and EU Commissioner for Trade (up to 2004), powerfully argued in a recent France 24 interview, Trump is an “idiot who doesn’t understand economics” and his “trade policies are stupid” and will inevitably cause a world recession, as demand from America falls short.

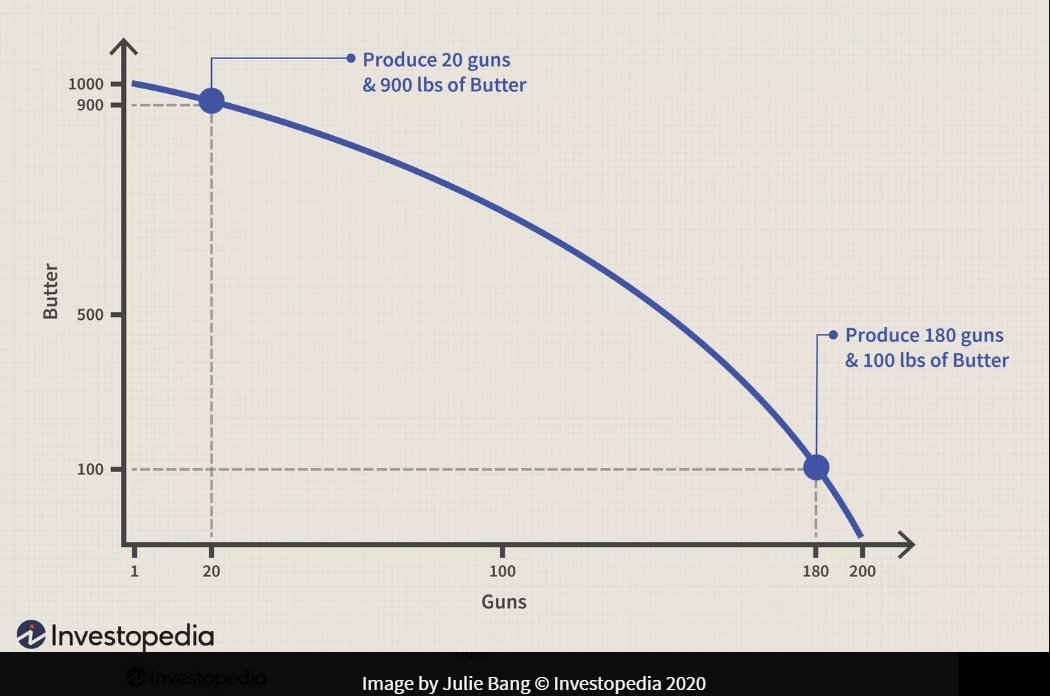

Unfortunately, most people don’t realize the role military spending plays in the civilian economy. Classic economics would have us believe that we have a choice between guns and butter, and all we can do is choose the most comfortable spot on that curve. Since Americans have always chosen to spend their money on guns in their role as defender of the peace and international order, Europeans have felt comfortable enjoying their butter.

The curved line on the diagram shows all the possible combinations of “guns” (meaning military expenditures) and “butter” (civilian goods) that can be produced when an economy’s resources are fully and efficiently employed. The curve demonstrates that to produce more of one good (“guns” or “butter”), a nation must produce less of the other. This “loss” is the opportunity cost.

That, of course, is both woefully simplistic and misleading. The guns-butter diagram is unrealistically two-dimensional: We humans are not two-dimensional, nor are we frozen in time. Whatever we do, whether we eat butter or produce guns, has an impact over time on the rest of the economy. Because making butter and guns both require labor. But working in the military industry has a far greater impact on technology than butter-making. The “opportunity cost” for guns is not a cost but a real opportunity.

Guns are a technological product; as such, they stimulate technical progress. The military is always looking for more effective weaponry. That means more investment in R&D (research and development). Inevitably, choosing guns calls for improving technology, stimulating invention and technical innovations.

That — the necessary focus on R&D — has been the historical key to American leadership in all economic areas over the past 80 years. Notably, digital tech developed in the 1970s and 80s, which gave America a second, post-industrial period of unprecedented growth.

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) played a pivotal role in shaping American technology, with impacts that extend far beyond military applications: Without DARPA investment, space exploration, and the Internet would never have been born, and Silicon Valley wouldn’t be where it is today.

Remarkably, the percentage of America’s GDP spent on military expenditures decreased over that period, from the 1960s to the present, even though more was spent on guns than anywhere else in the world, and this upward trend in military spending continued right through the fall of the Soviet empire up to now, as this diagram shows (source: macrotrends):

What this diagram shows is that, strikingly, despite its high and rising military spending, the American economy boomed. The economic pie grew larger, and the slice spent on weaponry smaller.

In short, America was able to have both its guns and butter. How could that happen?

How military expenditures jumpstart economic growth: The American model

Nobody explains this phenomenon better than British-Italian-American economist, Mariana Mazzucato. She is known for her work on the role of the public sector in innovation and her books, such as “The Entrepreneurial State” and “Mission Economy,” emphasize the government’s crucial role in driving innovation and shaping the economy. In particular, her work features analysis of how government programs, like those from NASA and DARPA, have been integral to technological innovation in America.

Mazzucato strongly advocates for exactly what I am arguing here: A reevaluation of the public sector’s role in creating value within economies, notably the key role of military expenditures.

In short, whether you give it the resounding name of “ReArm Europe” or the somewhat weaker sounding “Readiness 2030” and “SAFE,” its greatest benefit, besides providing the defence shield Europe needs, is purely economic: It will boost innovation and sustain economic growth, exactly as it had done for America when President Kennedy tasked NASA to reach the moon.

If Europe wants to live up to its historic destiny as the cradle of Western civilization, defending freedom and democracy, it’s time to adopt the NASA model, as Mazzucato advises. In an Impakter article four years ago, I referred to her advice and suggested that the G20 should adopt a public policy of investments NASA-style as a model to stimulate economies and achieve the SDGs.

By now, it is abundantly clear the world will never achieve the SDGs by 2030, but the EU could not only re-arm itself but also ensure that the investments are

(1) entirely local (buy European!) and

(2) intertwined with the private sector.

That is something the EU Commission can and should oversee. There is no need to “invent” a commission for the purpose; we already have at hand all the monitoring capacity in Brussels to keep every EU member on track and ensure the necessary collaboration.

This public-private approach is something the EU can do today: All it will take is a clear political vision and strong will on the part of EU political leaders. They need to understand the stakes and give their full support to the von der Leyen defence plan.

For a recent, striking example of how this military-industrial complex fueled by public sector investment works, consider this latest invention to provide better, more reliable predictions of climate change: Exclusive interview: How IBM and NASA’s foundational model will transform climate forecasting.

So “Re-Arm Europe,” no matter what you call it, is really Re-Boost Europe. It is the kind of government expenditure that Europe has never engaged in, leaving it to America without realizing that, by doing so, it was missing out on the most important benefit: The essential boost to innovation, which was always the key to not only the rise of Silicon Valley but more generally, American leadership globally and in all sectors.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Cover Photo: European fighter planes Source: Screenshot from Europe SKY SHIELD Plan for Ukraine STUNS Russia, a video from Military Show, 23 March 2025.