Picture a wind turbine on a hillside or an electric vehicle humming through the streets of a major city. Inside, powerful permanent magnets made from lithium, cobalt, and nickel, among others, combined with high-strength alloys, quietly enable its revolution. Neither of these green technologies would exist without rare earth metals.

Yet here lies a paradox: China currently accounts for over 50% of the global market in mining, refining, and magnet manufacturing, effectively suffocating the market from upstream to downstream. This bottleneck can potentially stall global net-zero targets, and as demand for permanent magnets surges with electric vehicles and renewables, many policymakers are asking: Can Greenland become an alternative to Chinese dominance?

The answer is complex. Greenland does possess genuinely world‑class rare earth deposits, including one of the largest known ore deposits in Kvanefjeld. Yet access to these resources hinges not on mining capacity, but on how rare earths behave in the ground, how they are mined and processed, and how a handful of countries currently dominate those stages. To see why Greenland looks so tempting and why it is no simple fix, we first need to understand what rare earths actually are and why they matter.

What Are Rare Earth Metals?

Firstly, the terms “rare earth metals, “rare earth elements”, and “rare earth minerals” are all essentially the same in principle and are often used interchangeably. However, the term “rare earth” is a misnomer. For example, Cerium is an element commonly used to make TVs, yet, despite being classed as a “rare earth,” it is more prevalent than copper, tin, or lead in the Earth’s crust. The “rare” label reflects not true scarcity but a geological quirk, as these 17 elements concentrate in economically mineable quantities only under specific geological conditions.

This creates the fundamental extraction problem: they rarely occur as pure deposits and are difficult to separate from one another. They frequently occur in association with radioactive uranium and thorium, complicating both mining and processing. When concentrated in ore bodies, however, they appear in specific mineral forms: bastnasite, monazite, and xenotime, known as “the workhorses of commercial mining”.

The elements are divided into two groups based on their chemical properties. Light rare earths, such as lanthanum through gadolinium, are more abundant and easier to extract; heavy rare earths, such as terbium, lutetium, and yttrium, are scarcer and often in greater demand for cutting-edge applications. Greenland’s deposits are valuable precisely because they contain substantial concentrations of heavy rare-earth elements, which are rare outside China.

The environmental footprint of extraction is steep, as processing these ores requires crushing, leaching with sulfuric or hydrochloric acid, multiple solvent extraction steps, and pyrometallurgical refining. As a result, each phase is energy-intensive and chemically demanding, often producing significant tailings with trace levels of radioactivity.

Why Rare Earth Metals Matter to Modern Tech and the Green Transition

Walk into a smartphone factory and look for rare earths: you will find neodymium in the speaker magnet, and terbium and europium in the display phosphors. A wind turbine’s permanent magnet generator requires 150-600 kilograms of rare earth alloy per megawatt, dominated by neodymium, dysprosium, and praseodymium. An electric vehicle’s motor contains 1-2 kilograms of permanent magnets, and the battery relies on lanthanum and cerium. These are not niche applications; they are foundational to the technologies driving decarbonisation.

According to Natural Resources Canada, the largest share is attributed to magnets (45.7%), followed by catalysts (16.4%), while polishing powders, metallurgical uses, glass, ceramics, batteries, phosphors, and pigments make up the rest.

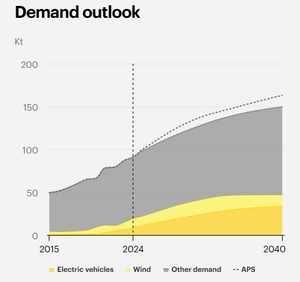

Furthermore, according to the IEA’s 2025 Global Critical Minerals Outlook, these figures are expected to rise. Rare earth demand is led by magnet elements like neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium, and terbium for electric vehicles and wind turbines, with total magnet rare earth metals use expected to double from 2024 to 2050, and clean‑energy applications taking an ever‑larger share.

Hence, the critical constraint is not total abundance but the supply security of specific elements; without them, electrification stalls, and the uncomfortable truth is: you cannot meet net-zero without rare earths. The green transition is not an alternative to resource extraction; it is a more demanding version of it. This reality explains why governments are frantically seeking new sources beyond China’s control.

Why Supply Is a Geopolitical Headache

For decades, rare earths barely registered as a geopolitical issue. American mines dominated until the 1990s, when China, with cheaper labour, looser environmental rules, and larger ore bodies, captured the market.

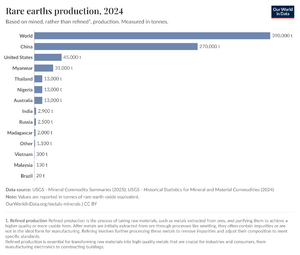

Case in point: as of 2024, data shows that the world mined around 390,000 tonnes of rare earths, and China single‑handedly accounted for about 69% of that total.

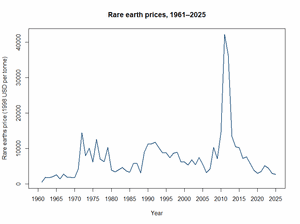

The shock came in 2010–2011, when China halted rare-earth exports, triggering a massive price spike per tonne from 14,500 1998$/tonne to 42,100 1998$/tonne (from $28,832.94 to $83,714.95, adjusted for inflation). Hence, the US scrambled to reopen the Mountain Pass mine, and Australia’s Lynas Rare Earths began large-scale production. Furthermore, because China controls over 50% of the entire rare earth value chain, from mining to processing and magnet manufacturing, it can undercut new entrants on price, effectively squeezing them out of the market through sheer scale and cost advantage.

For governments in the US, Europe, and Japan, rare earths have shifted from obscure industrial inputs to strategic materials, due to their concentrated supply and the difficulty of finding alternatives. Strategic minerals policies differ by country, creating friction in supply chains and raising procurement costs.

On the ground, these supply‑chain risks materialise as environmental and social damage: in China’s mining regions, rare earth extraction has led to tailings leakage, groundwater pollution, and community health impacts. While in Malaysia, opposition to Lynas Corporation’s processing plant has centred on fears of radioactive waste. These cases show that without strong environmental and social safeguards, ‘diversifying’ supply can simply relocate harm to another jurisdiction rather than reducing overall risk.

Greenland: Geology Meets Politics

Greenland sits atop one of the world’s richest deposits of rare earth metals. The Ilímaussaq complex in southern Greenland hosts multiple significant projects, most notably Kvanefjeld and the emerging Tanbreez field. Kvanefjeld alone is estimated to contain over 800 million tonnes of ore with 8–11% rare earth oxide concentration, making it globally competitive in both scale and grade. The deposits are particularly valuable for their high rare-earth content, especially dysprosium, which is scarce outside China. Geopolitically, Greenland is attractive: it sits in the Arctic, close to North America and Europe, and is tied to NATO rather than China, hence for the US, EU, and allied nations, a Greenlandic rare-earth supply would be a strategic coup, diversifying away from single-country dominance while strengthening Western Arctic presence.

Yet geology is only half the story. Kvanefjeld has flirted with starting mining operations since the 1970s, yet has produced not a single tonne. Why? Because of interlocking barriers such as uranium-thorium co-occurrence, public opposition, and unclear profitability relative to Chinese production costs. The uranium–thorium problem is not trivial: Kvanefjeld ore contains significant uranium alongside rare earths, so every project has to confront radioactive waste and health concerns head‑on.

In 2021, Greenland’s Inuit Ataqatigiit party won parliamentary elections and immediately passed legislation banning the exploration and mining of mineral deposits with a uranium concentration over 100 ppm (parts per million), effectively blocking the development of the Kvanefjeld rare earth mine, which has a uranium concentration of approximately 300 ppm. As of now, development of the Kvanefjeld has been in litigation since 2022, but it could end within the next year, as Greenland could be forced to pay the operator of Kvanefjeld, Energy Transition Minerals Ltd. (ASX: ETM), a total of $11.5 billion. Until those processes conclude, any start date for Kvanefjeld remains uncertain and speculative, so watch this space.

Yet despite these domestic constraints, international interest is intense. China, the US, the EU, and even Japan have explored options. Greenland is currently at a crossroads between Chinese interests, Western security concerns, and local self-determination; this tension ensures that the mineral geology is not the binding constraint on production.

Related Articles

Here is a list of articles selected by our Editorial Board that have gained significant interest from the public:

Looking Ahead: Uncomfortable Trade-Offs

Meeting net-zero energy targets and ensuring supply-chain stability for rare earths creates an unavoidable trilemma: decarbonisation speed, environmental protection, and geopolitical risk management cannot be optimised simultaneously.

The questions are hard:

- On speed: How much new mining (on land or seabed) are we willing to tolerate, and on what timeline? Greenland’s deposits are large, but developing a mine takes 10–15 years from permitting to first ore. Meanwhile, demand grows yearly. Can substitution, recycling, or efficiency gains buy time?

- On fairness: Should countries like Greenland become “rare earth states,” economically dependent on exporting these metals to fuel others’ energy transitions? And on whose terms? Local control, national revenue, or international oversight?

- On alternatives: How much can recycling and material substitution realistically blunt future demand? Currently, recycling recovers less than 1% of rare earths from end‑of‑life products. Substitution in permanent magnets is largely infeasible without performance loss.

No perfect solution exists. Expanding Greenlandic, Australian, and North American production will reduce Chinese leverage but requires accepting mining’s environmental and social costs. Recycling is essential, but at current rates, it is insufficient, and substitutions are limited.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of impakter.com — In the Cover Photo: A fragment of chalcopyrite, pentlandite, and pyrrhotite. Cover Photo Credit: USGS.