In the climate movement, we often hear, “climate justice is racial justice” because we typically focus on the disproportionate effects on both the production and impact sides of the climate crisis. The fossil fuel complex routinely exposes poor communities of color to the burdens of toxic pollution. We also know many communities in the Global South are experiencing the impacts of climate change at a higher rate, despite having little to no responsibility for the emissions that cause it. Both class and race enter into the equation to produce the climate emergency we face today.

I will admit, I’ve always been dissatisfied with the politics of disproportionality. Is the goal to achieve “fair distribution” of the “burdens” of the climate crisis as some environmental groups suggest? If so, wouldn’t we still be facing a planetary climate crisis?

I’m currently finishing a book entitled Climate Change as Class War. It argues climate change is at its core a class struggle.

In current political discourse, many assume a class focus is necessarily distinct from one centered on racial justice (or that they only “intersect” as distinctly separate variables). I would suggest this is only evidence of a shallow conceptualization of class as a descriptive characteristic based on income, occupation, or education.

Climate Change is a Class Struggle

I draw from a Marxist conception of class rooted in one’s relationship to the “means of production.” While this phrase suggests old slogans of socialist movements, a class analysis rooted in production takes on new meaning in the age of climate breakdown.

Production is at the core of the ecological relationship between humans and life. How we produce our food, energy, and other material necessities is also at the core of the climate crisis.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, industrial production alone constitutes 32 percent of collective emissions – ahead of all other sectors including buildings, transportation, and land use. Under capitalism, most production is for profit, notably the production of fossil fuels, but also carbon-intensive sectors like cement and steel that together make up 15 percent to 17 percent of global carbon emissions.

We tend to think of our responsibility for climate change in terms of our consumption or “carbon footprint” (e.g. household electricity use). Such an approach not only erases industrial production but also fails to acknowledge that other capitalist producers make a profit from our consumption; these producers at least deserve a share of “our” carbon footprints.

When we start to think of class as a relationship to production, suddenly race – or, racism – is not something distinct from class, but constitutive of class systems of power overproduction. What was plantation slavery but a racialized mode of production?

This system generated immense wealth and helped establish the U.S. as a major global power. Yet, as Barbara and Karen Fields remind us, we should not think of plantation slavery solely in terms of racism, “as though the chief business of slavery [was] the production of white supremacy rather than the production of cotton, sugar, rice, and tobacco.”

To be clear, I don’t mean all forms of racism are rooted in class and production. Certainly, there are assorted forms of hate and discrimination that take place outside production or the private workplace. My point is that a production-rooted theory of class helps us explain how racism structures class power.

Related Articles: Environmental Racism: Why Does it Exist? | The Science and Politics of Geoengineering

Racism, Class, and the Climate Crisis

This particular analysis has a connection to the climate crisis because the very systems of production at the core of the crisis are rooted in racialized modes of capital accumulation.

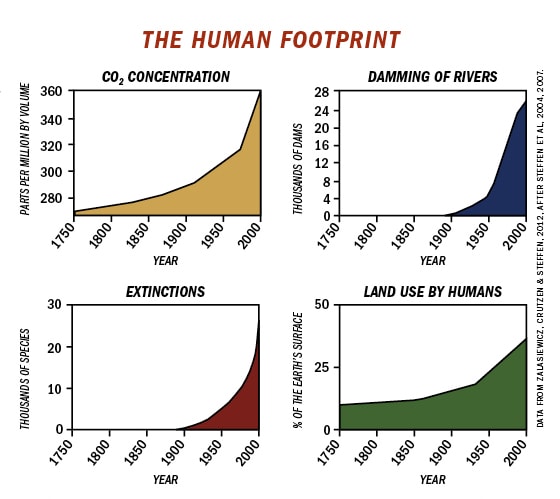

Post-World War II, capitalism in the U.S. was understood as a Fordist regime of accumulation based on mass production for mass consumption. This was of course a carbon-intensive mode of accumulation – including emissions from the oil, steel, auto sectors, and energy-intensive suburban life. Historians have labeled this era “The Great Acceleration” where all environmental indicators skyrocketed.

This regime of accumulation was predicated on suburban property ownership. As George Lipsitz reports, between 1934 and 1962, The Federal Housing Administration, together with the Veterans Administration subsidized over $120 billion in new housing to the American public, with less than two percent of this figure allocated to nonwhite families.

This was a mode of capitalist production dependent on racialized forms of housing segregation. In fact, when Black families attempted to integrate during the 1950s white communities in places such as Levittown, Philadelphia, broke out in riots.

Many Black individuals gained waged employment and actively organized unions in factories after migrating from the South. Yet it did not take long for those factories to shut down leaving racialized poverty in its wake.

Environmental Racism in “Cancer Alley”, Louisiana

The network of chemical factories and refineries along the Gulf Coast has been the center of environmental justice organizing against toxic pollution and death in predominantly Black or low-income communities. Specifically, environmental justice organizers call the corridor of factories along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans “Cancer Alley.”

This carbon-intensive production not only poisons these communities but also represents a whole geography constructed from the historical legacy of racist production and wealth accumulation. As scholar Barbara Allen shows, these chemical companies purchased large plots of land along the river from former sugar plantation owners, the plantation system made such land acquisition simple for industrial chemical capital.

I spoke with a daughter of a plantation owner who sold their land to ammonia producers. She lamented the sale as sullying an idealized past, “…Maybe it’s a romanticized idea of plantation life…Why ruin that beautiful land with those nasty looking chemical factories?”

While she views chemical production as the degradation of a nostalgic landscape, it is more accurate to describe “Cancer Alley” as the replacement of one racialized mode of production with another. It represents how historical legacies of race and class persist in the land, air, and water today – and, indeed, in the changing climate.

Furthermore, many of the Black communities that live within sight, smell, and breath of these toxic infrastructures were themselves set up by the “Freedmen’s Bureau” meant to allocate land to freed slaves in the Reconstruction South. As Allen makes clear, “not only is their property part of their identity, it is the only real thing of economic value they have.”

As W.E.B DuBois illustrated, we can connect the poisoning of these Freedmen communities to a prolonged history of reactionary backlash against the promises of Post-Civil War reconstruction.

When history and moral conviction create what Andreas Malm calls a “temporality of exasperation” it is up to social movements to demand their abolition.

As the climate movement increasingly calls for “carbon abolition” – and this goal is increasingly a scientific necessity – we should recall how previous abolitionist organizing had to directly confront the planter class who profited from production.

While the fossil fuel industry is currently projecting unconvincing plans to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, this class will always resist what history requires at every step.

Both climate change and racism are deeply embedded in the very structure of our society. If we are to dismantle those structures, we need to understand these problems as not just surface-level disproportionate impacts. A class focus on production clarifies the enormity of our challenge, but history shows that “abolition democracy” (DuBois) can be won through social struggle.

—

Matt Huber is an Associate Professor of Geography at Syracuse University. He is the author of Lifeblood: Oil, Freedom, and the Forces of Capital (University of Minnesota Press, 2013). His new book Climate Change as Class War will be out from Verso Books in 2022.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Chemical plants, which line the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans are visible from Louisiana’s State Capital. This part of Louisiana is known as “cancer alley” due to industrial pollution which contaminates the air, land, and drinking water often causing cancer. Featured Photo Credit: Flickr.