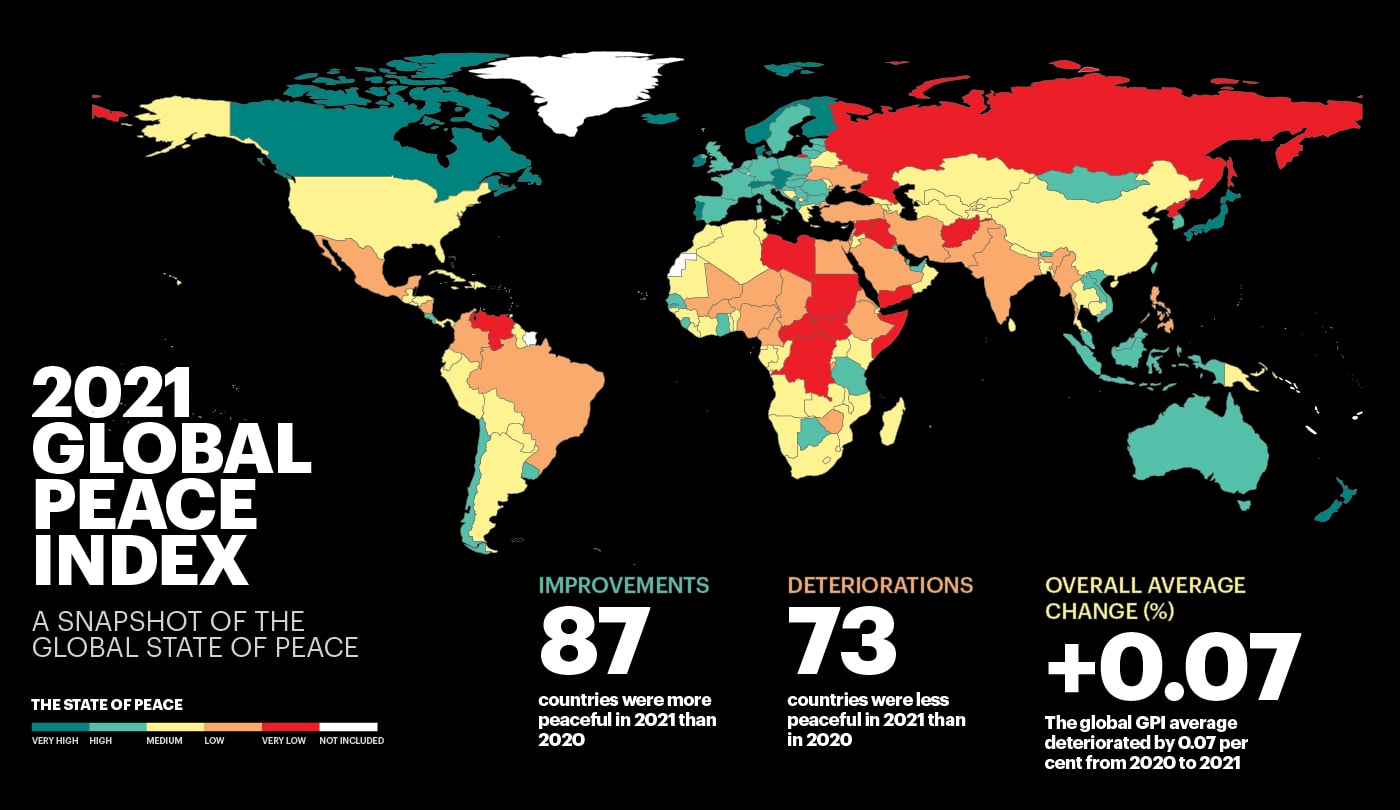

Since the global wars of the 20th century, there has been a focus on ensuring the world never sees such widespread conflict again. Institutions like the League of Nations and its successor the United Nations sprung to be houses of peace negotiations. Formal commitments followed, with nations signing and ratifying international documents. The second half of the 20th Century had an international focus on preventing a repeat episode of these tragedies even while struck by the paralysis of threatening nuclear war.

Now, humanity is facing challenges unparalleled in history. New global issues call for new global solutions. Climate change, decreasing biodiversity, over-population and new technology present complex and multidimensional challenges. Necessarily, the world must reframe its focus to invest in opportunities to thrive, rather than focusing on delivery responses to threat. The solution to these issues is positive prevention techniques, rather than emergency responsive approaches.

PHOTO CREDIT: Annie Spratt

Positive Peace provides a new way of conceptualising the way communities can develop in order to sustain peace or to recover from conflict. The focus is too often on responding to violence or the threat of violence. The Institute for Economics and Peace empirically derived the Positive Peace schema to address the lack of prevailing guidelines countries could use in their journey towards meeting peace goals. Positive Peace puts forward the framework for investment in the presence of attitudes, institutions and structures that create and sustain peaceful societies.

Positive Peace investment promotes the optimum environment for human potential to flourish: in a personal, societal, and economic sense. Grasping Positive Peace doesn’t only prevent violence. Many desirable characteristics of society ensue with robust investment in Positive Peace, like a thriving economic environment and low levels of corruption. The Institute for Economics and Peace produces an annual Positive Peace Index that ranks 163 countries on their commitment to levels as peace, as well as a Positive Peace Report. The pillars of Positive Peace are closely tied with all of the Sustainable Development Goals, especially Goal 16: Promote just, peaceful, and inclusive societies. There are eight pillars of Positive Peace.

PHOTO CREDIT: Institute for Economics and Peace

To fully grasp Positive Peace, one must understand the inextricable nature of the pillars. When one pillar improves, it’s expected another should improve in tandem. The elements of Positive Peace are cohesive because they target key elements of society: attitudes, institutions, and structures. For example, high levels of human capital will likely result in a sound business environment. The greater “stock” of potential a society has from increased education, health, and youth development; the more economic value the citizens possess. Yet High Human Capital and Strong Business Environments are enabled through a Well-Functioning Government. Each pillar can act as a driver for the growth in another pillar. A statistical evidence to this is the IEP analysis of corruption demonstrates that 80 percent of countries scoring poorly in Low Levels of Corruption, also score poorly in High Levels of Human Capital. The pillars are interdependent.

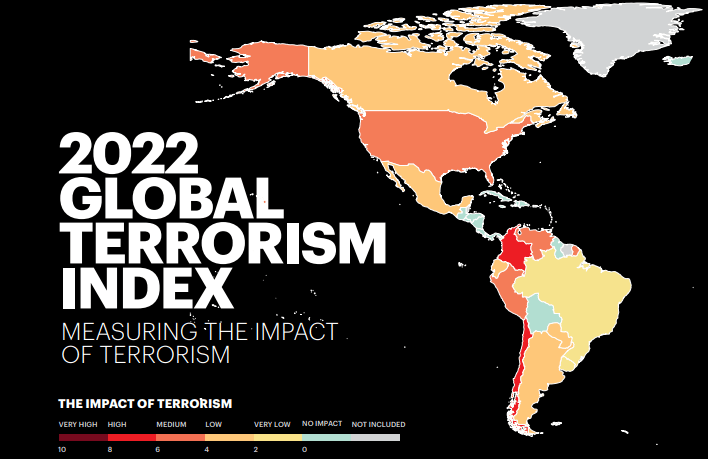

However, IEP’s research has found that unequal progress in Positive Peace may have negative effects. For example, the increased allocation of funds to education for youth development improves the High Levels of Human Capital pillar. Though, if the economy is not healthy enough to absorb this educated generation into the market then grievances may develop. A market flooded with university graduates without jobs may have an effect of radicalisation. This is a grievance militant organisations in the Middle East and North Africa leverage for youth recruitment.

It would be remiss to suggest that simply throwing money at the eight pillars of Positive Peace will sustain peace or recover communities in a context of conflict. The investment in the pillars has a timely connection to their stage of transformation into peacefulness.

PHOTO CREDIT: Institute for Economics and Peace

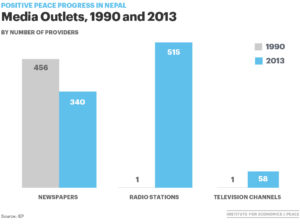

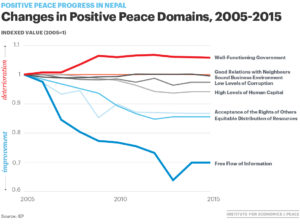

An apt case study here is Nepal. After a decade-long internal conflict, a Comprehensive Peace Agreement was signed in 2006 marking the cessation of violence. The majority of violence stopped. Anyone could note that in comparison to the years before, Nepal was peaceful. Nepal was characterised by the presence of Negative Peace. In order to sustain a society resistant to the threat of violence, investment in Positive Peace is necessary. The Nepalese progress towards Positive Peace was driven by focusing on the weakest pillar: Free Flow of Information. This impacts how informed citizens are, and the rationality that crises are responded to with.

PHOTO CREDIT: Institute for Economics and Peace

In 1990, there was just one Nepalese radio station, and one television channel. By 2014, Nepal had 515 radio stations and 58 TV channels. Peaceful countries have free and independent media that disseminates information in a way that leads to greater openness and helps society and individuals to work cohesively. By 2014, Nepal’s phone subscription rate reached 83 per 100 people. A 59 percent increase of mobile phone subscriptions over a five year period has supported Nepal’s Positive Peace progress. By investing in an individual pillar, Free Flow of Information, Nepal has also seen marked progress in the pillars Acceptance of the Rights of Others, and Equal Distribution of Resources. By equipping a community with quality, free and accessible information, the citizens are afforded a chance at resilience to crisis. Thus, Nepal has moved away from being a community characterised only by the absence of violence. Instead, Nepal is characterised by a commitment to attitudes, structures, and institutions of Positive Peace.

For the purpose of looking at the economic benefit of the Positive Peace pillars, we can turn to Rwanda. In 1994, an estimated 800,000 Rwandans were killed, and 3 million were displaced, in the space of 100 days in internal conflict. The genocide was enabled by a structurally flawed society. About 85 percent of Rwandans were part of the Hutu ethnic group. The minority that had long held power, the Tutsis, were targeted by Hutu extremists. The country was devastated and society crumbled.

IN THE PHOTO: Rwandan children dance in a circle in the shadow of one of several volcanoes which loom over the Rwandan refugee camps March 15, 1995. PHOTO CREDIT: REUTERS/Corinne Dufka

The Rwandan recovery continues to be held as a positive example in the international community. The current President Paul Kagame has been hailed for the rapid economic growth of the tiny African country, achieved through investment in Positive Peace tenets. In a state of recovery, Rwanda invested significantly in education and health. By 2005, the primary school enrolment rate had reached 95 percent. This statistic is a testament to the economic and social benefit of investment in human capital, as the percentage of the population living in poverty decreased from 78 percent to 57 percent in the same period. It dropped further to 39 percent in 2014. Economically this has been incredibly fruitful. Rwanda’s GDP has grown nearly 9 percent annually from 1995 to 2014.

The crucial nature of peace to global development is underscored by Goal 16 of the SDGs: Peace, Justice, and Governance. The pillars of Positive Peace provide guidance about the active steps towards achieving these goals on a local and global scale. Countries evolve in unique ways and paces, hence the need to be understood and practically nurtured towards peace. Once a commitment to Positive Peace has been established, a virtuous cycle of improvement and support for peaceful structures begins.