I am fortunate to have a wide circle of progressive intellectual friends, but I am worried about them. There is a good reason for that. Unlike most of them, I’ve had the lucky experience of meeting early in my life an activist who knew how to organize for political success: How to move from protest to a movement to political change. My friends who haven’t had the same experience, have been in a state of grief and horror for almost four years now, alternating between outrage and helplessness, talking and talking about what they don’t like in American politics, their astute analyses often dissolving into the plaintive query “what can I do?”

If you reframe their question as “But what can I do” there is a simple answer – nothing. There is nothing you can do about societal problems as an individual. Tufts University professor Eltan D. Hersh, the author of Politics is for Power, deplores in a New York Times Op-ed, aptly titled Listen Up, Liberals: You Aren’t Doing Politics Right, the news bingers, on-line debaters and kitchen-table exasperators who are emotionally invested but do not participate in political life.”

Among “educated whites” whom he surveys, “one-third of his respondents” reported two hours a day consuming news and thinking and talking about politics. Of those, very few spent more than a trivial amount of time working in organizations.” “But if liberals,” he concludes, “shy away from face-to-face political communities, choosing to spend their free hours as at-home hobbyists rather than participating in weekly political meetings and canvasses, they should expect to reap as little as they sow.”

In an article about how Climate Research Needs a Better Understanding of Power, science journalist Sara DeWeerdt concurs that “What’s needed now is research on tactics and strategies at the organizational and societal levels: moving beyond public opinion and messaging to get elbow-deep in how the proverbial sausage is made.”

COVID restrictions have not kept me and my friends from our political sausage-making. In this article, I will explain both pre-pandemic and pandemic modes of getting this job done.

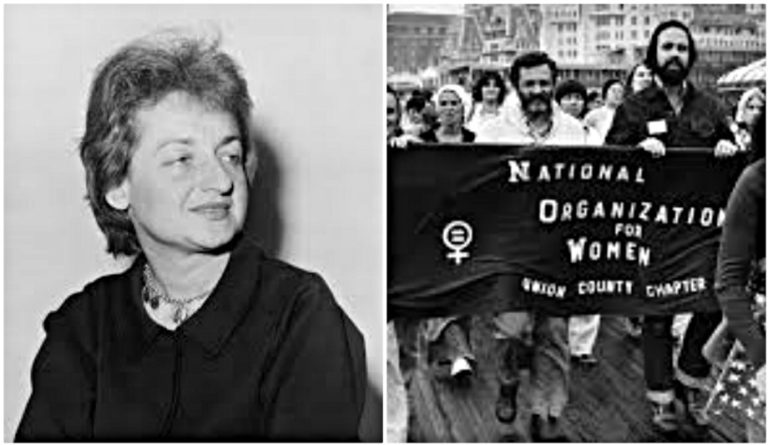

My First “Political Success” Experience: the National Organization for Women

Let me take a step back in time. In 1967, I felt helpless to the point of depression because Emory University in Atlanta, where I taught part-time, refused to consider me for a full-time job because Henry, my husband, worked there too. An enterprising feminist, Henry thought this nepotism rule might be illegal, so he got on the phone with Betty Friedan in New York, already at the time a noted feminist thanks to her 1963 bestseller The Feminine Mystique.

Betty Friedan agreed, reassuring us that the NOW leadership was working on an Executive Order to withhold federal funds from Universities that discriminated against women. As a kind of quid pro quo, she asked the two of us (men were active NOW members in its early years) to organize a NOW chapter in Atlanta.

The whirlwind of getting our Chapter started, hosting Betty’s visits to Atlanta, appearing on television and radio to talk about equal rights for women, collaborating with Nurses’ unions and Welfare organizations – lifted me out of my lonely funk. Eventually, it paid off handsomely: I was hired and promoted when the University of Wisconsin-Madison came under pressure from the federal government.

In contrast to the Women’s Liberation Movement, which got started soon after NOW and prided itself for being “structureless,” NOW had rules and by-laws, procedures, and directions for every aspect of our work, from the national to the local level. There were by-laws for chapter meetings and officer duties, how-tos for media contacts and press releases, and detailed instructions for coordinating every chapter in the country to hit the media with protests on the same day.

The Example of RESULTS

NOW’s strategies and tactics bridged the gap between my remaining a helpless individual and becoming a politically engaged one. You can see the same kind of approach NOW used in the work of Sam Daley-Harris.

When Sam Daley-Harris founded RESULTS in 1980 to work on poverty issues, he wanted to teach individual Americans how to develop the “political will” to influence change.

Like the founders of NOW, he was convinced that volunteers needed structure to participate in what he termed “deep advocacy.” He applied the term “trim tabbing,” which involves using small surfaces to change an aircraft’s performance, to teaching volunteers how to lobby members of Congress.

“My life’s work,” he wrote in Reclaiming Our Democracy: Healing the Break between People and Government, “is to empower individuals to work with others to joyfully make the difference in the world they always dreamed of making.”

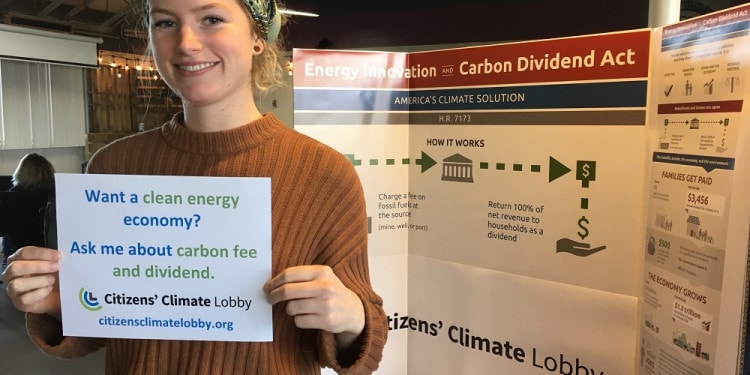

The Citizens’ Climate Lobby

My experiences with NOW taught me the importance of choosing one organization in the political movement I supported. When I felt helplessly anxious about the threat of climate change and decided to become active in environmental causes, my choice fell on the tightly organized Citizens’ Climate Lobby (CCL) with its cheerful local Chapters intent on developing the political will to enact a specific carbon fee and dividend legislation.

CCL’s founder, Marshall Saunders, launched it in 2007 under the tutelage of Sam Daley-Harris. CCL’s goal became “thousands of ordinary people organized, lobbying their members of Congress with one voice, one message, and lobbying in a relentless, unstoppable, yet friendly and respectful way.”

Fast forward to 2017, when protesters from the Resistance movement gathered every day outside our Republican Congressman’s office to demand that he hold a town hall. They yelled “coward” at his windows and brandished rubber chickens to emphasize their disapproval.

If, as Sarah Deweedt suggests in her article about “making political sausage” (para.4), “What climate advocates need to know is how to build enduring relationships with political decision-makers,” was this the way to do it?

Although the Resistance got good media coverage (which may have influenced his stepping down before the 2018 election), their relationship with their Member of Congress was neither enduring nor endearing.

That was why I was not among them. CCL’s strategy involves developing a relationship of mutual trust with Members of Congress through the tactic of long term civil conversation. I had already been visiting my member of Congress for several years with CCL members from his congressional district, lobbying him to co-sponsor the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act.

For an example of CCL’s conversational tactics, here is how our meetings were organized:

- We start with an affirmation, a statement of gratitude for an action our member of Congress has taken.

- We ask for his/her views on environmental issues and listen as he/she talks to discern goals we hold in common.

- We speak from those mutual interests, then provide information on carbon fee and dividend policy.

- We have one “ask” per meeting. For example, “Would you consider joining the Climate Solutions Caucus in the House of Representatives?

- We provide or update a notebook of carefully organized background materials and remind him/her that we are willing to be resources on any further environmental questions as time goes on.

By no means a moderate, our Congressman came out against Pipeline 5, which endangered Lakes Michigan and Huron; he signed a letter to President Trump asking him to urge Canada not to dump Nuclear Waste near Lake Huron; he joined the Climate Solutions Caucus in the House of Representatives and, to top it all off, co-sponsored the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Bill when it was introduced in the House of Representatives late in the 2018 congressional session.

Results/CCL methods seek the development of political will in both constituents and Members of congress through mutual trust; we are given monthly practice sessions for dialogues with even the most virulent opponents. The strategy is to pay Respectful visits with Members of Congress all over the country for a period of years, using the tactic of civil discourse to achieve legislative results.

Movement Formation

In the same way that an individual is empowered through participation in a like-minded organization, NOW, Results, and CCL achieve wide-reaching results by combining forces with other groups pursuing similar agendas.

Although tensions can arise over different methods (as between NOW and Women’s Liberation and between the NAACP, SCLC, and the Black Power Movement) long-established groups like the Sierra Club and The League of Conservation Voters can multiply their impact by finding common ground with more recent climate advocates, like the Green New Deal.

It was when a broad coalition of activists, particularly religious leaders, found common ground with Dr. King that the Civil Rights Movement achieved the passage of key legislation. Christians, Jews, Muslims, Hindus, and other faiths have all written stewardship of our beloved planet into their missions, working together to collaborate in environmental advocacy. With the exception of one recent example, Interfaith Power & Light, a coalition of religious environmentalists is contributing to the 2020 election season by partnering with the Environmental Voter Project on a Faith Climate Justice Voter campaign.

What about Resistance?

In The Path of Greatest Resistance, David Cole, National Legal Director of the ACLU and law professor at the Georgetown University, worries that demonstrations and marches do not, in and of themselves, create movements.

“The challenge is this,” agrees Sarah Deweerdt: “in most cases, the null assumption is that activism becomes power at scale: that collective action is merely the sum of its parts, and the more people who take action, the more likely a movement is to achieve its goals.”

Historically, mass demonstrations are both tools of recruitment to causes and the end result of long-term planning. The Selma March, the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the March on Washington, and the Poor People’s Campaign came after years of honing strategy and tactics so that the resulting events would galvanize national support for the Civil Rights Movement.

Recent events have demonstrated the impact of interest groups and Resistance working in tandem for political change.

Vast numbers of feminist and environmental protestors who marched in Washington and other cities after Trump’s 2016 inauguration went home to organize successful 2018 campaigns.

This year, similarly, Black Lives Matter protests have not only led to police practice reforms but galvanized voters: “Voter Registration Surged in June,” reported the New York Times (August 11), drawing on the enthusiasm generated by the protests following the killing of George Floyd in police custody.

There is a significant difference, however, between violent and non-violent protests. Under both Gandhi and Dr. King, a tough-minded self-exposure to violence out of an ethic of love for one’s opponents has proven effective in achieving political results; while violent protests accompanied by rioting and loot undercut the political will of potential recruits.

You can see this playing out this week in Kenosha Wisconsin, where looting and rioting are doing as much to help President Trump’s re-election as all of the political speeches. David Leonhardt, in a New York Times article titled “The Debate Over Riots,” comments that “No one can know for sure, but there is evidence suggesting that violent protests — like the ones this week in Kenosha, Wis., in response to the police shooting of a Black man in the back — help the politician whom many protesters most despise: President Trump.”

As Gandhi and Dr. King would attest, a tightknit, detailed organization is the key to political success.

Take Great Britain’s Extinction Rebellion, led by Gail Bradbrook and Roger Hallem. With a strategy to “not only to tap into progressive concerns about social justice and equality, but also traditionally conservative themes such as national security and protecting family,” Extinction Rebellion organizes community-based street demonstrations with the goal of mass arrests.

“By the end, XR’s representatives were sitting down for talks with senior politicians and ministers in the UK. Supporters and funders – many of whom had been skeptical before April – showered praise and money on the new movement, and in the weeks that followed, the UK parliament and scores of councils around the country declared a climate emergency.”

There were problems, however, with the Resistance Rebellion’s basic structure: it became more and more decentralized, endured contentious splits about class and race inclusion, and operated without commonly agreed-upon rules for the organization.

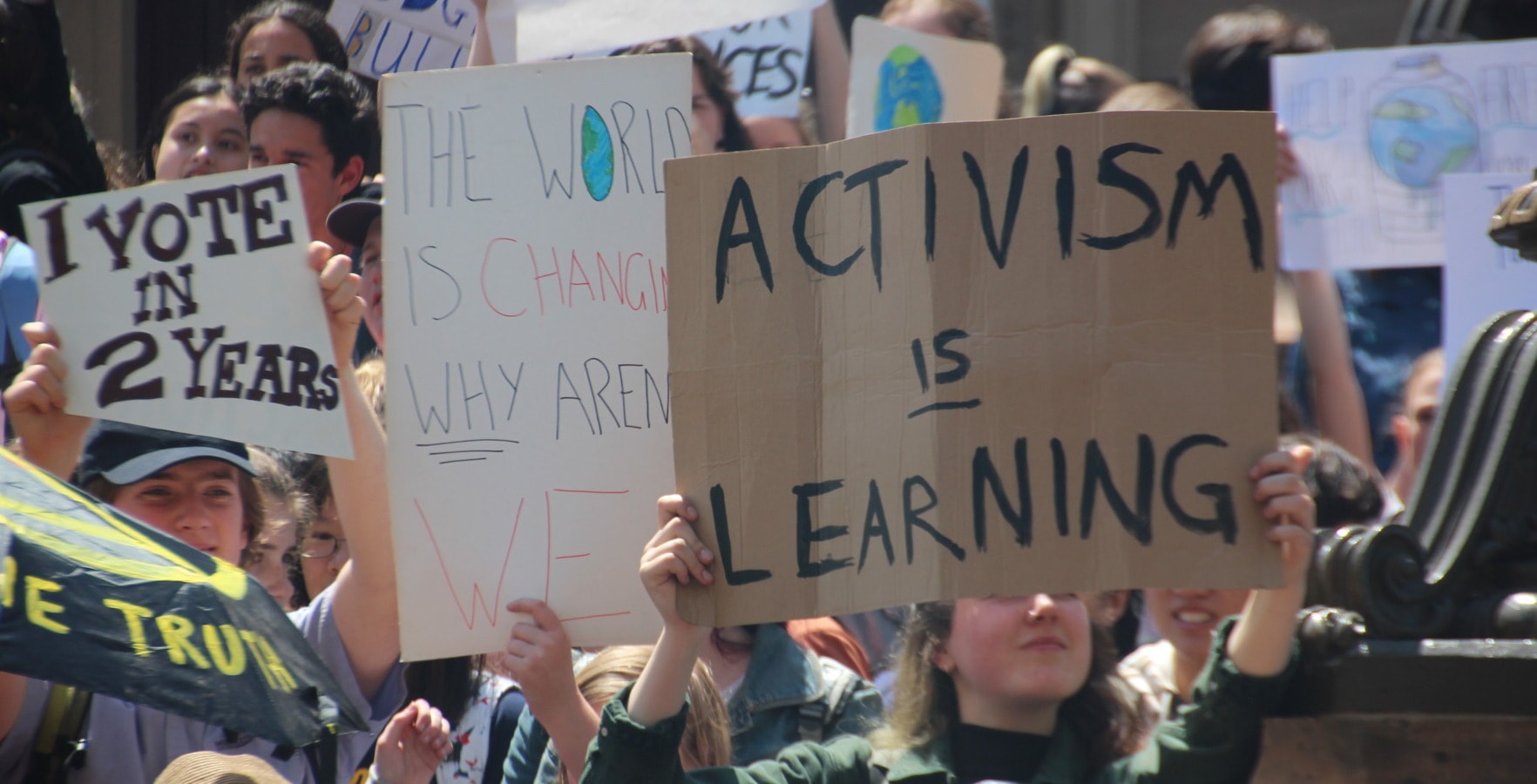

Young environmentalists have also displayed a need for a tighter structure.

In the widespread movement that began with the student strikes of 2018, they did not articulate long term, step-by-step political methods for getting adults to adhere to their demands.

Youth climate activists Greta Thunberg, Luisa Neubauer, Anuna de Wever, and Adélaïde Charlier, who are justifiably furious at adults whose inaction denies them their future on the planet, recognize that “This mix of ignorance, denial, and unawareness is at the very heart of the problem. As it is now, we can have as many meetings and climate conferences as we want. They will not lead to sufficient changes, because the willingness to act and the level of awareness needed are still nowhere in sight.”

In the video: Greta Thunberg speaks after meeting Angela Merkel to discuss climate crisis August, announcing the next strike scheduled on 25 September 2020 – Streamed live on 20 Aug 2020 Source: Reuters

If you understand “willingness” as “political will,” you can see that the School Strike movement, like the Resistance Rebellion, needs to develop mutually held by-laws and common practices for each unit of the organization.

Making Pandemic “Political Sausage”

The Resistance Rebellion and the School Strike movement use social media to spread their messages exponentially.

Although I agree with Cole that “Whether #MeToo and other progressive movements will achieve lasting reform will depend on these organizations working collectively in multiple forums, including courtrooms, state legislatures, corporate boardrooms, union halls, and, most importantly, at the ballot box,” I disagree with his (pre-pandemic) insistence that “We all need to turn away from our smartphones and screens and engage, together, in the work of democracy.”

In a time of isolation and social distance, meetings and canvases are impossible. Nonetheless, I am as busy as ever “making political sausage”.

The pandemic may keep me from schmoozing at political picnics (my favorite type of summer activism), but we Citizen’s Climate Lobbyists are spending as much time as ever publicizing our favorite Congressional legislation, contacting our members of Congress and making use of a variety of databases to encourage potential voters.

And it is my smartphone and screen (especially Zoom) that keep me active.

Flashback to 1967 when we established that first Atlanta Chapter. It involved telephone calls back and forth to Betty Friedan (a hard person to reach, which she made up for by calling us day and night), a telephone tree for letting members know about actions and meetings (extremely time consuming, as our landlines didn’t record messages) and tons of slow-moving snail mail.

Fast forward to 2020, when our political effectiveness is exponentially strengthened by social media. Everything you ever wanted to know about lobbying, from wonky legislative details to talking points, can be found on the Citizens’ Climate Lobby website. There is a subgroup for every talent and interest: as a writer, I am alerted to local newspaper articles so I can write letters to the editor, and a Social Media unit notifies me when and what to Tweet and Post. Both our national and local chapter meetings meet monthly on Zoom.

Conclusion: Walking the Talk for Political Success

But what about my hyper-intellectual friends who “don’t like to join things” and seem to consider thinking and talking sufficient responses to our troubled times? What about their question “but what can I do?”

Although I have laid out here plenty of things they can do if they join an organization to forward their convictions, I have not explained how to get out of their individual boxes to develop political will in the first place.

Will has to do with choice, with our capacity to make decisions; the choices we make depend (even if are unaware of it) on our philosophy of life.

My friends who consider ideas more important than actions are in accord with Plato’s idealism. My own position, that life does not consist of ideas but of actions, derives from Aristotle.

Outraged helplessness, a sense that nothing you can do will change anything, springs from a hyper-individualistic view of life that is the bedrock of libertarianism, but goes all of the way back to Cynicism, a classical philosophy holding that individual self-interest rules everything and that social norms are ridiculous.

If there has ever been a time for figuring out the philosophy we are actually living by, this medically and economically destructive pandemic, with its reminder of our mortality and individual helplessness, is a good time to sit down with a scratch pad and actually do it.

Every world religion has taken a position on environmental theology (see my Impakter article on “How to Address Climate Grief for a list of these). If you are of a secular frame of mind, Deep Ecology reminds us that we are embedded in an interdependent web of being impacted by our decisions, so that we must sustain not only ourselves but all of the life forms that share our beloved planet.

In these difficult days, I often consider how the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, (who began his rule in 161 CE) took solace from Classical Stoicism. As his empire crumbled all around him, he sought equanimity, a stalwart quality of mind that provides strength to endure whatever comes our way and yet remain wholehearted.

For those who consider cultivating individual “self-actualization” as the goal of life, it is hard to grasp the Stoic conviction that the only good worth pursuing is the common good. Or, as Marcus puts it, “the mind of the universe is social.”

My hope for my progressive intellectual friends is that they develop a philosophy based on the common good that will give them the political will to join like-minded organizations and plunge into the heady task of making political sausage.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. In the Featured Image: Citizens’ Climate Lobby is laser-focused on getting a Carbon Fee and Dividend bill passed at the national level. That effort recently received a boost when over 3,500 economists endorsed “Economists’ Statement on Carbon Dividends.” first published in the Wall Street Journal on January 16, 2019. Photo credit: Kristina Lindborg