In both American and European political life, we have separated ourselves into stubborn tribal enclaves. Having set up positions from which we refuse to budge, we are deadlocked into animosity against each other – just like a stubborn elephant. This puts at risk the democratic process that requires allowing the majority view to prevail.

How did we get this way? Is there any way to escape our righteously opinionated ideologies?

Although it is our capacity for reason that distinguishes us from other mammals, it has become evident that our mammalian emotions have a much larger input in our decision-making than we had thought.

I facilitate a local Socrates café ©, where our members write down questions and then vote about which one to tackle. The question we discussed last week was “Is it possible to make a logical or rational decision without letting emotions have an influence?” Do you notice that this is “begging the question,” in that it has already answered itself by assuming that emotions need to be controlled so that a proper (aka “reasonable”) decision can be made?

This basic Western European assumption that cognition and emotion are opposites and that reason ought to rule the emotions is what Social Psychologist Jonathan Haidt challenges in “The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion” (published by Knopf, 2013). He argues, in a nutshell:

“If you want to change people’s minds, you’ve got to talk to their elephants”.

Haidt marshals a wide range of data and scientific analysis to demonstrate that split-second intuitions (which only sometimes manifest as full-blown emotions) determine what you decide.

These intuitions/emotions are your elephant; your reasoning powers (neo-cortex) are the elephant’s rider, who evolved in order to carry out the wishes of the elephant. “The first principle of moral psychology is Intuitions come first, strategic reasoning second.” Without the elephant, you can’t make choices, as demonstrated by the fact that patients who have sustained damage to the parts of their brain where emotions are generated cannot make decisions at all.

Your elephant is social

When do elephants listen to reason?

Under social persuasion: “But the bottom line is that when we see or hear about the things other people do, the elephant begins to lean immediately. The rider, who is always trying to anticipate the elephant’s next move, begins looking around for a way to support such a move.”

What kind of social signals is your elephant responding to?

That depends upon the culture you have been brought up in. “The moral domain varies by culture…cultural learning or guidance must play a larger role than rationalist theories had given it.” You are born into a culture with specific “moral foundations,” your brain open to cultural influences during your upbringing: “You are not hard-wired at birth but wired with the potential for growing your moral system in a number of different directions.”

Has anyone ever seen two chimps carrying a log together?

Apparently not! Chimp expert Michael Tomasello discovered that, although chimps are very intelligent, when tested against toddlers on a problem that could be solved by social cooperation, they totally failed to help each other out.

His evolutionary finding is that “human cognition veered away from that of other primates when our ancestors developed shared intentionality.” When you add language to cooperation, you find bands of humans who are intelligent enough to plan complex moves and who extend these moves over time through oral (and, later, written) tradition, you have the dispersal of homo sapiens from our African origins into the entire world.

What Haidt terms “groupishness” is thus an inherent human trait, and the glue holding us together is moral: “Humans construct moral communities out of shared norms, institutions, and golds that, even in the twenty-first century, they fight, kill, and die to defend.”

Where we humans stand: 90% Chimp, 10% Bee

Bees are totally social creatures, their entire identities devoted to their particular contribution within their hive. They all respond as one, for example, when a threat (smoke) or a benefit (pollen blowing on the wind) comes to their attention. In most social situations, even at our most cooperative, we humans retain a sense of our individual selves as we participate in group activities.

But we have moments, Haidt argues, when we become entirely and absolutely groupish. He calls this the “hive switch,” citing Emile Durkheim’s conviction that “collective emotions” can pull us out of our ordinary endeavors into a place “where the self disappears and collective interests predominate.”

“Switch flipping” into a hivish mode of being happens to us at a muscular and cognitive level, as in group dancing, or when we are “carried away” cheering for a football team, or at a political rally.

Unlike bees, our social and cognitive brains have evolved to internalize disparate sets of cultural signals, moral dictates determined by the norms we have accepted or by social values we have decided to live by.

Haidt divides these “moral foundations” into three basic types:

WEIRD: Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic cultures live by belief in individualism: human existence takes place within personal boundaries, and each of us is a self-contained decision-making unity. Western cultures are organized around social values that emphasize the individual member: fairness, for example, by which everyone follows the same rules; and care, meaning that everyone has a right to have their needs seen to by their group.

COMMUNITY: Community-based societies practice sociocentric morality: a person must modify his/her behavior according to group norms. When Haidt traveled to India, he discovered that his western values of “equality and personal autonomy” must be set aside in favor of “a moral world in which families, not individuals, are the basic unit of society, and the members of each extended family (including its servants) are intensely interdependent.”

DIVINITY: These are systems based on the idea that a person is a “temporary vessel housing a divine soul.” “The body is a temple, not a playground. . .many societies, therefore, develop moral concepts such as sanctity and sin, purity and pollution, elevation and degradation (to whom) the personal liberty of secular Western nations looks like libertinism, hedonism, and a celebration of humanities baser instincts.”

Political elephants

Although in many instances these features overlap between systems, you can see these features impacting the political arena. In the United States, liberal Democratic elephants lean toward fairness in sharing goods, especially if it means taxing the 1% who are rich to care for the 99% who are not.

They stomp their feet fiercely when individual rights are threatened, as in the Supreme Court’s decision overturning individual women’s ability to determine their reproductive fate.

Community, for America’s Conservative Republicans, means adherence to historically valued social institutions: same-sex and transgender marriages are abominations because “family values” apply only to traditional heterosexual arrangements.

To MAGA (Trumpist Make America Great Again) Republicans, White racial supremacy is taken as a historically validated absolute. That is why, now that the U.S. population is approaching the tipping point to “majority minority, ” a powerful hiving switch has stimulated their fear of “Replacement.”

In Conservative cultures worldwide, values take on the strength of super glue when you throw religious ideas into the mix, with traditional holy books – the Bible, Torah, the Koran – cementing rigid convictions. Loyalty and obedience are absolute to these cultures, while apostasy – an individual rebelling against group norms – is even worse than western liberal modernism, and brings down the harshest of punishments.

Haidt demonstrates the psychological impact of political affiliation by wiring up Liberal and Conservative students to measure their reactions to politically-charged values.

Liberal students are surprised when Care and Fairness are called into question and don’t like sentences endorsing “Loyalty, Authority, and Sanctity,” the very topics that trigger Conservative neurons:

“Within the first half second of hearing a statement, partisan brains were already reacting differently. These initial flashes of neural activity are the elephant, leaning slightly, which then causes their riders to reason differently, search for different kinds of evidence, and reach different conclusions. Intuitions come first, strategic reasoning second.” (bolding added)

A little utopian fantasy in which we talk with other people’s elephants

If a whole group of MAGA elephants comes stomping towards us, liberal outrage will superglue us into (to scramble my metaphor) intractably mindless hives. Let’s assume we’re riding along on our elephant with “I Read Books” inscribed on our cap (an elitist symbol that maddens Conservatives with our presumed intellectual superiority).

And here comes an elephant whose rider is wearing a MAGA hat, which usually makes our elephant see red.

However, the threat to the planet’s ecosystem has gotten the attention of our two elephants. An existential need to do something before the sixth extinction is upon us has led them to set aside their mutual animosity and break from their herd to seek mutual solutions.

The riders find themselves warily aligned, side by side.

Nudged by his peace-minded elephant, the liberal rider says something like “I am glad to meet you; I’ve been really curious about the kind of needs you have and what political solutions you have in mind to meet them?”

The MAGA elephant realizes that the signal was not hostile; in fact, this other elephant seems to care that she exists. She stops tossing her head and leans slightly toward the Liberal elephant.

“Actually,” says her rider, “I’m worried about my job. I live in Kentucky. I’m from three generations of coal miners. If your battle against the mine succeeds and it closes down, then where will I be? I have four kids!”

“I know what you mean,” replies the liberal rider. “My university is acting more and more like a business, treating workers as poorly as possible. I’m just an adjunct – I don’t have any benefits or health insurance. I am terrified that they are going to let me go!”

“But you are the ones that came up with this global warming hoax that is ruining my life!”

“About that, did you know that there are openings in the Wind Power business for workers laid off from the coal mines, with free training and opportunity to rise from the bottom up to management? They pay well.”

“Gosh! Maybe I can get a job there and you can be one of the teachers!”

As their riders continue their conversation, their elephants tramp along, side by side, fanning each other with their ears.

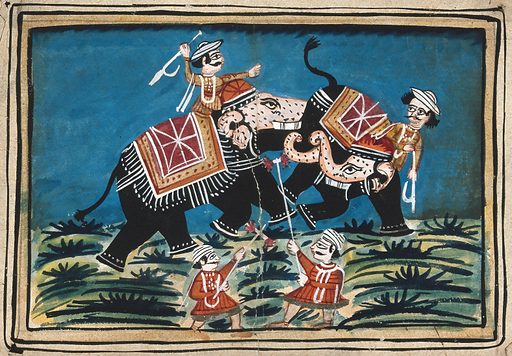

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Two men on elephants and two men on the ground engaged in battle. Gouache painting by an Indian painter. Created between 1800 and 1899. Wellcome Collection Source: Work ID: pggtpspt Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)