In years past, flares up on the Korean peninsula between the Communist North and Democratic South could only be found buried within the World News section of a publication. 2017 thus far has proved to be different.

For months, North Korea has defied the international community by testing a series of medium-range missiles. Each test in turn brings more ominous warnings from the US government that has warned that all options were on the table.

This new period of heightened tension stems in part from the new American administration under President Donald Trump who is the first chief executive to enter the Oval office without any political or military experience. At the other end of the world, DPRK Supreme Leader Kim Jong-un is also a relative newcomer to international relations after inheriting his father’s seat in 2011.

This combination of inexperience has the world asking, “Are we on the brink of World War III?”

While this article cannot serve as a crystal ball, it can examine the issue in greater detail. Specifically, we will look at the nations involved in the Korean standoff, which in many ways has come to resemble a nuclear poker game.

North Korea

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union more than a quarter-century ago, the Democratic People’s Republic of North Korea (DPRK) stands alone as the last communist dictatorship in the world. The end of the Cold War and the globalization trend that followed have done little, however, to expose the Asian nation to outsiders and little remains known about the country. DPRK Supreme Leader Kim Jong-un’s motives for his bellicose military posturing of late is consequentially impossible to fully understand and has led scholars, policy experts and military minds to drum up a medley of theories.

“North Korea is the most isolated, least understood country in the world,” said Dr. Jim Walsh, an expert in international security, who attempted to analyze the rationale behind the North Korean leader’s recent aggressive behavior in an Al Jazeera editorial.

“North Korea doesn’t want a war, because it knows it will lose and lose decisively,” Walsh wrote. “That would mean the end of the Kim dynasty. And if there’s one thing Chairman Kim Jong-un wants, it’s to stay in power.”

This doesn’t mean that North Korea wouldn’t launch a preemptive strike or fire a nuclear missile. According to Walsh, Kim might consider a nuclear strike to deter the aggression he is witnessing from the United States and its allies. He also points to military doctrines, poor communication and a general lack of understanding of the enemy’s intentions that could potentially ignite such a conflict.

Regardless of Kim’s motives, analysts from across the globe continue to study North Korea’s military capabilities in order to prepare for any sudden attack. including nuclear war.

To date, the country has successfully tested five nuclear devices. Once again the reasons behind pursuing a nuclear policy when such a course would inevitably lead to stricter international sanctions and further isolation are unknown.

American Admiral Harry Harris attempted to rationalize North Korea’s nuclear policy when he told a Congressional delegation last month that such weapons serve as a deterrent from foreign intervention. Otherwise, he noted, the Kim dynasty would face an existential crisis.

In the photo: North Korean Victory Day Parade in 2013. Photo Credit: Stefan K. via Flickr.

North Korea’s arsenal is limited, however, and it is unlikely that the peninsula would become the staging ground for a nuclear Armageddon. Nonetheless, a significant amount of nuclear material is available to annihilate millions in the area. With this grim scenario a possibility, analysts have turned their attention to North Korea’s technological abilities to deliver such a lethal payload.

Many have seen the North Korean military parade its soldiers, tanks and missiles through its capital, Pyongyang, but observers are quick to ask whether those missiles are indeed capable of hitting Japan or even the United States. North Korean ballistic missile tests, such as the one in May, are not new either. Skeptical commentators and pundits will frequently show scorn at each failed test and claim that even if the North Koreans had a significant nuclear arsenal, they wouldn’t have the means to deliver such a weapon.

Security experts are not as confident. The striking distance of these missiles and their various models range from 1300 km to 8000 km. While other factors such as guidance technology continue to mitigate the creep of North Korea’s nuclear shadow from approaching American shores, next door countries like Japan and South Korea remain potential targets.

South Korea & Japan

At the other end of its arsenal sit North Korea’s neighbors South Korea and Japan. These nations have had a long history of bad relations, spanning roughly from Japan’s feudal era through the Korean War in the 1950s. While many former members of the communist bloc have either transitioned to liberal democracies (e.g., Poland) or embraced quasi-capitalist policies (e.g., Vietnam), North Korea remains antagonist to the West and its alleged puppet states.

Despite Seoul being a mere 35 miles away from the North Korean border — where an estimated 20,000 artillery batteries are located — Vice reported that life for most South Koreans is still business as usual. Military flare-ups and war games are the norm here and the South Koreans and the Japanese are accustomed to the evacuation drills and alert mechanisms in place were an attack to occur.

Fears of doomsday are also alleviated by the South Korean and Japanese militaries that routinely train with the American forces in the area. In addition, the US has supplied the two nations with Patriot PAC-3 anti-missile systems that can be used to intercept incoming low-altitude projectiles.

This isn’t to say that the relationship is without complications.

A new defensive array being introduced in South Korea by the Americans has recently sparked controversy throughout the region. At the center of the debate is the American THAAD anti-missile program that is currently being rolled out on the peninsula. The $1.2 billion project was criticized by some South Koreans who protest the American military’s presence in the region, which they see as a potentially destabilizing force.

TIME magazine covered South Korean protests in Seongju where demonstrators carried signs reading “No THAAD, No War,” and “Hey USA! Are you friends or conquering troops?” In one case, Reuters reported that ten protesters were injured when demonstrators clashed with local police.

In the photo: Gwanghwamun Square, Seoul. The SK capitol is 35 miles away from the DMZ. Photo Credit: Flickr.

However, China is easily seen as the biggest critic of THAAD. The communist country shares a border with North Korea and has vociferously opposed the anti-missile system by claiming that THAAD has the capabilities to check high-altitude Chinese missiles. Chinese delegates have also objected to THAAD’s accompanying X-Band radar system, which they claim can peer into its borders — the standoff is similar in many ways to Russia’s resistance to NATO’s anti-missile arrangements.

As is common in the history of arms races, China may ultimately upgrade its arsenal to counter what it views as a Western containment policy. Partly because of THAAD and the American presence nearby, it is therefore important for the Chinese to tacitly support the North Korean regime. This antiquated type of Cold War relationship has led to a troublesome balancing act as China works to juggle national security while maintaining access to global markets.

China

North Korea owes its very existence to China, whose People’s Liberation Army checked the advance of UN forces during the Korean War. Much has changed since the Cold War thawed in the early 1990s and now China more or less views its Communist neighbor as a buffer zone between itself and the American forces stationed in South Korea.

The result is a very one-sided relationship.

China accounts for 90 percent of North Korea’s trade and there are signs that this too is eroding. In February, China dealt a series of economic blows to its neighbor when it placed restrictions on banking and banned coal imports after growing increasingly frustrated over the country’s ongoing nuclear weapons program. Mined out of its northern mountains by its slave population, coal has been North Korea’s biggest export for decades, and the sanctions could be one reason for Kim’s war posturing.

All of this doesn’t imply that the Chinese are pushing for the collapse of the Kim dynasty, however. “The second to last thing China wants is a new Korean War,” said Salvatore Babones. “But the last thing China wants is a united Korea under South Korean leadership.”

A comparative sociologist at the University of Sydney, Babones is also a specialist in global economic structures. In his Al Jazeera editorial, he argues that if North Korea were to fall, a tidal wave of refugees would flood into China and create a humanitarian crisis.

“If China does intervene in North Korea, it won’t be to topple the Kim regime and promote peaceful reunification,” Babones wrote. “It will be to prevent a collapse of the Kim regime in the face of domestic mismanagement and American pressure. Kim may go, but China will make sure that the regime remains.”

Despite unsubstantiated claims that the PLA has mobilized 150,000 troops on the Korean border, China continues to push for a diplomatic solution to the standoff. “The use of force does not solve differences and will only lead to bigger disasters,” Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi argued at the UN in April. Wang then proposed that talks resume between the powers in the area on the condition that North Korea freeze its military programs and the US and South Korea halt their military exercises, PRI reported.

Whether this will actually bring North Korea back into China’s folds is anyone’s guess at this point.

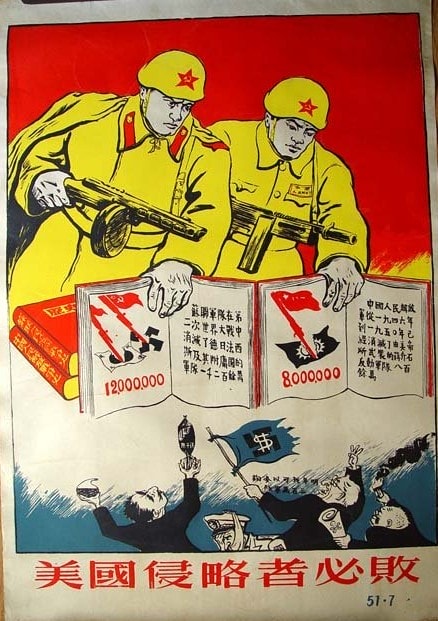

In the photo: A Chinese propaganda poster highlighting the PLA’s success against UN forces in the Korean War. Photo Credit: Jason Ford via Flickr.

United States

Sitting across from Minister Wang, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson bluntly warned the UN Security Council of the “catastrophic consequences” if it failed to act. According to the BBC, Tillerson also said that his country would act in order to prevent North Korea from developing missiles capable of reaching the United States.

Only five months into his tenure at the state department, Tillerson has been proactive in promoting the Trump administration’s foreign policy agenda.

“We do not seek regime change, we do not seek a collapse of the regime, we do not seek an accelerated reunification of the peninsula,” the former Exxon-Mobile CEO said in an interview with NPR. “We seek a de-nuclearized Korean peninsula. And that is entirely consistent with the objectives of others in the region as well.”

Tillerson’s hawkish resolve is matched by Vice President Mike Pence, who stopped in Seoul during his Asia tour and met with Hwang Kyo-ahn, the South Korean acting president. It was near the DMZ that Pence made headlines when he said that the “era of strategic patience was over” when it came to his country’s relations with North Korea.

“President Trump has made it clear that the patience of the United States and our allies in this region has run out and we want to see change,” Pence said. “We want to see North Korea abandon its reckless path of the development of nuclear weapons. Its continual use and testing of ballistic missiles is unacceptable.”

In order to bring North Korea into line, Pence, Tillerson and other American representatives have called on China and other UN members to pressure North Korea by enforcing the sanctions already in place. This includes bans on weapon sales, fuel and aviation exports as well as financial restrictions, the latter of which has been designed as a means to cut off funding for North Korea’s nuclear program.

“We call on countries to suspend or downgrade diplomatic relations with North Korea,” Tillerson said. “In light of North Korea’s recent actions, normal relations with the DPRK are unacceptable.”

In the photo: Gen. Vincent K. Brooks, United Nations Commander, Combined Forces Commander, and United States Forces Korea commander, and U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson speak at an observation point located within the Joint Security Area (JSA) inside the Korean Demilitarized Zone, Mar. 17, 2017. Secretary Tillerson made a stop in Korea during his first visit to Asia as Secretary of State. U.S. Army photo by SFC Sean K. Harp

In addition to UN members lacking the funds or political motivation to enforce such sanctions, analysts have found a litany of ways in which North Korea is able to defy sanctions and smuggle in weapons and gain access to financial markets. The coal ban, for example, can be thwarted by off-the-book deals and by lax enforcement of regulations.

As a result, some have called on the US government to start directly targeting the banks that are granting North Korea illegal access to finances. Anthony Ruggiero, a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, suggested that the United States should fine Chinese banks specifically. “A large fine would send shock waves through the Chinese financial system, causing other Chinese banks to evaluate their compliance procedures,” Ruggiero wrote for CSIS.

In the meantime, the USS Carl Vinson recently arrived off the Korean Peninsula where it joins the USS Michigan nuclear submarine. Combined with THAAD and the other military exercises in the region, the standoff is likely to continue until cooler heads prevail.