124 years ago, a brutal British punitive expedition tore through Benin City, burning and destroying the Royal Palace along with countless other monuments and palaces. A kingdom that had dominated and thrived for over seven centuries, home to perhaps the largest single archaeological phenomenon on the planet and incredible collections of art, was brought to a violent end. Today, the spoils of this war, most notably the Benin Bronzes, can be found 7,000km from their homeland, in the British Museum; but Nigerians want it back.

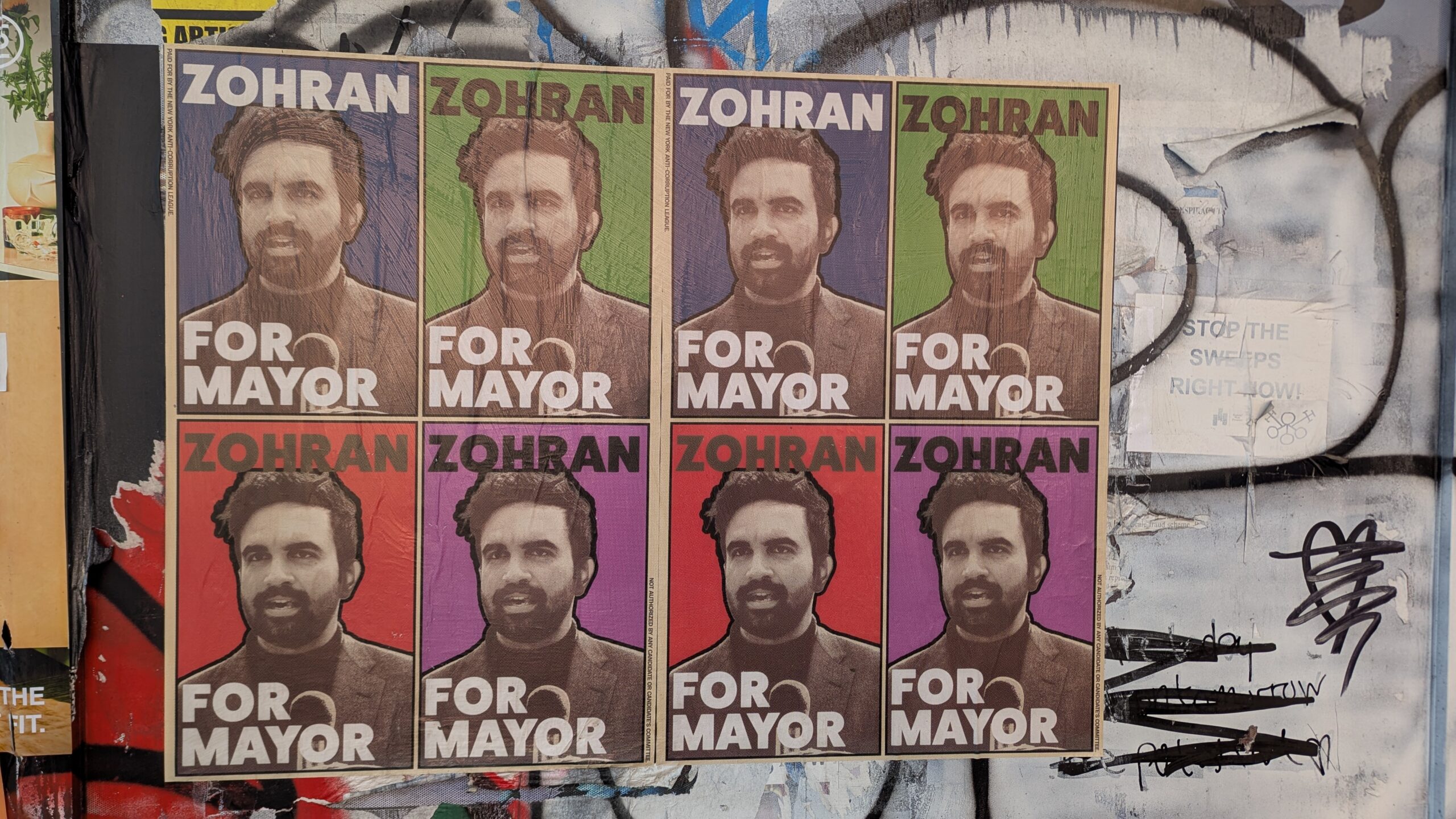

Although demands for the restitution of looted artefacts regularly line the news cycle, Nigerian artists have proposed a new approach to these discussions. The Ahiamwen Guild of artists and bronze casters is an organization based in Edo State, Nigeria (the home of Benin City). The guild has offered to donate contemporary artwork to encourage the British Museum to return the Benin Bronzes that have been stolen.

The Benin Bronzes are a collection of over 3,000 bronze and brass sculptures produced from at least the 16th century onwards. Originally used to decorate palace walls, they are among Africa’s finest and most culturally significant artefacts. . The plaques provided key historic records for the Benin Court and kingdom, illustrating historic practices and traditions.

“The descendants of the people who cast those bronzes, they’ve never seen that work because most of them can’t afford to fly to London to come to the British Museum,”

— Osarobo Zeickner-Okoro, co-founder of the new guild and the proposed donation instigator, speaking to Reuters.

The art form used to produce the Benin Bronzes is a complex process but it has not died out. Many of the modern artists though have never had the opportunity to see the original artworks and instead have to work from 2D images on a computer screen.

Zeickner-Okoro also takes offence to the Museums portrayal of his culture “as a dead civilisation… among ancient Egypt,” even though the art form is still thriving. The Guild hopes that the offering of contemporary artwork will allow the Museum to showcase Benin City’s modern culture without displays being tainted by colonial violence.

Related Articles: The Fight for Reparations for People of African Descent | Intra-Racial Conversations: Cultural Appropriation or Appreciation?

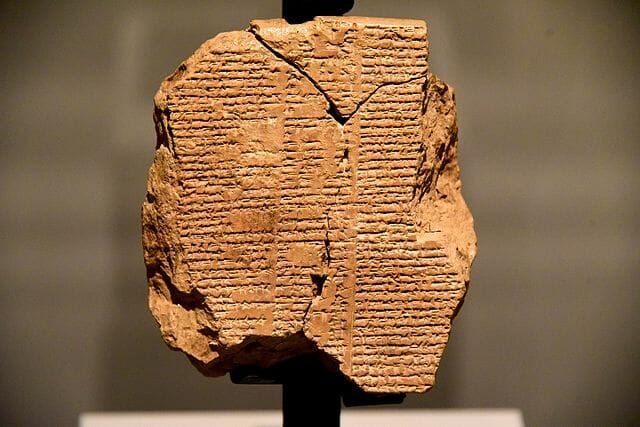

Many former colonies have been demanding stolen goods and artefacts be returned since they gained independence, and the Benin Bronzes have been among the most notorious. As society becomes more culturally sensitive and countries begin to reconcile with their colonial pasts, debates over returning cultural objects to their rightful place have gained momentum. Days before the Nigerian Guild made their offer, a 3,600-year-old “Gilgamesh” tablet was returned to Iraq by the United States. In July and August, hundreds of artefacts were returned to Pakistan from France and America.

In June, a Belgian collector was forced to return almost 800 artefacts (worth €11m) to Italy and an auction in Dorset had two items withdrawn after the Ethiopian government appealed to the auction house to “stop the cycle of dispossession.”

French President Emmanuel Macron revived the discussions and put pressure on other European governments in 2017 as he declared that “African cultural heritage can no longer remain a prisoner of European museums.” The President commissioned a report calling for thousands of African artworks residing in French museums to be returned to the continent they were originally stolen from. The report estimates that about 90% of Africa’s cultural heritage currently lies outside the continent.

In 2020, France’s parliament voted to return 27 artefacts to Benin and Senegal and in April 2021 Germany announced it would begin returning a “substantial” part of the artefacts it holds to Nigeria in 2022. Even the University of Aberdeen has promised to return their Benin Bronze after they found the item had been acquired in an “extremely immoral” manner.

The British Museum though is refusing to budge. The Museum holds the largest collection of Benin Bronzes; in fact, the collection is so large that only a portion of it can be shown at any point in time and the rest sits sealed away from all view. The British Culture Secretary has made it clear that this collection is unlikely to go anywhere.

https://twitter.com/Th3AfricanDiary/status/1440376778493607940?s=20

Not all demands for the return of stolen goods have specified physical restitution, some just ask for ownership to be restored to the rightful governments. These governments and institutions would then loan out the artefacts to share their culture with a world that previously thought of Africa as the “dark continent.”

British heritage laws prevent the British Museum from taking such actions though and the Culture Minister has stated that there will be no moves to repeal or reform them. However, this has not stopped critics from being vocal about the dishonour these displays bring to the British Museum and the need to take responsibility for past atrocities.

Leading human rights lawyer, Geoffrey Robertson QC, wrote: “Politicians may make more or less sincere apologies for the crimes of their former empires, but the only way now available to redress them is to return the spoils of the rape of Egypt and China and the destruction of African and Asian and South American societies.”

As Robertson concludes, “We cannot right historical wrongs – but we can no longer, without shame, profit from them.”

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Benin Bronzes on display. Featured Photo Credit: Archie.