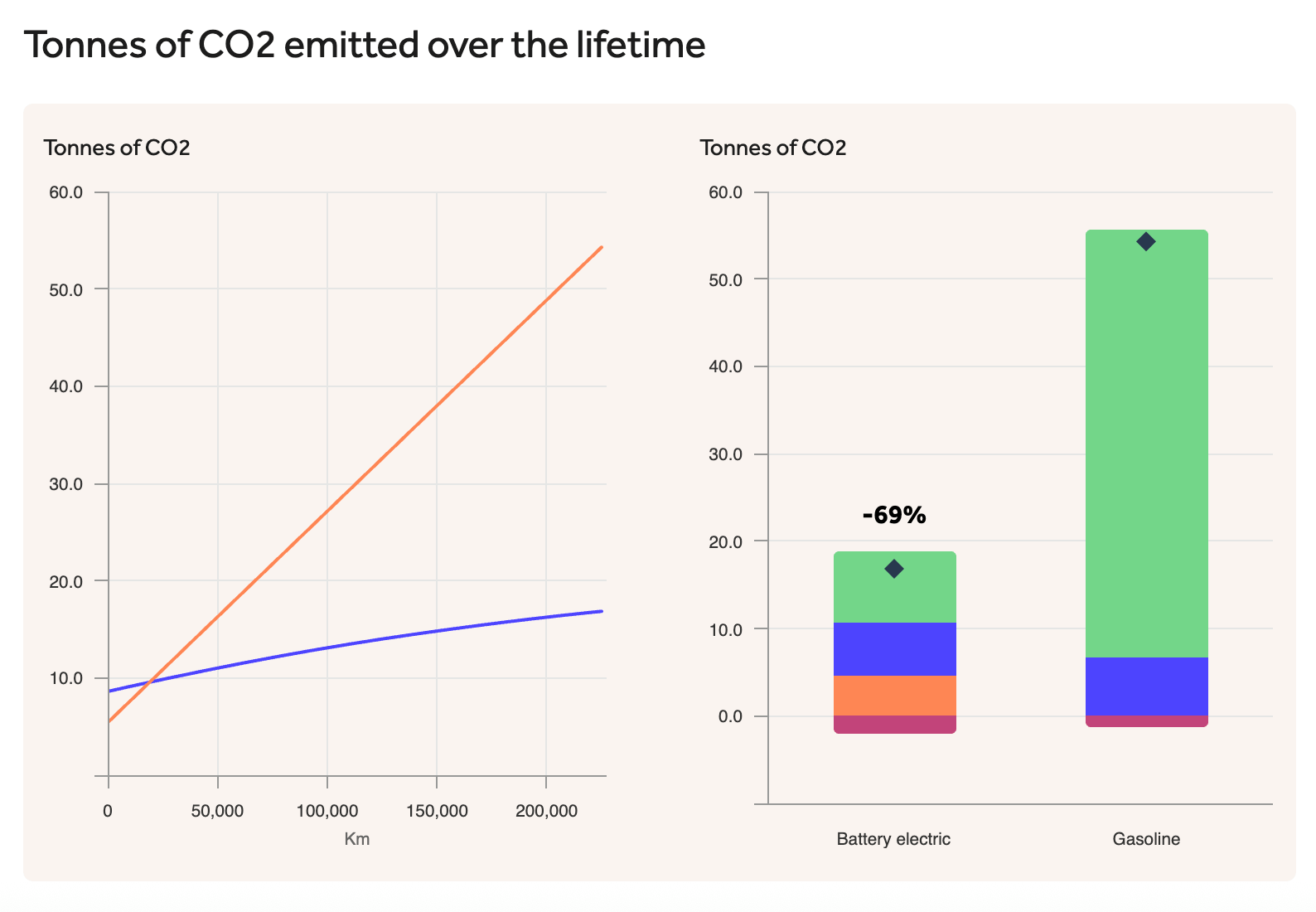

Electric vehicles (EVs) are often regarded as a carbon-neutral way of transportation with zero tailpipe emissions. Yet reality is more complex: EVs emissions are typically higher than ICE vehicles after production because producing a battery for one is much more carbon-intensive than producing an internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicle, creating a carbon debt.

The central question, however, is not whether the carbon debt exists or whether it makes EVs less sustainable, but rather how quickly and under what conditions it is repaid.

The energy sector evolves quickly. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) has become the standard framework for comparing EVs and ICE vehicles, but the results may vary drastically. An EV bought today will spend most of its life cycle powered by a grid cleaner than the current one, and its life cycle emissions will depend on how much cleaner future grids will become — and at what pace. Some measurements are more optimistic about grid decarbonisation than others, which creates a global debate.

This article explores how different regions — the United States, European Union (EU), and East Asia — assess the carbon debt of EVs and the speed at which it is being repaid. Ultimately, understanding carbon debt is key to climate policies, credible corporate reporting, and realistic public debate.

American EV carbon debt measurement methods: the perfect balance

The US approach to analysing EV carbon debt is concise yet effective. The US Department of Energy and Argonne National Laboratory have established a practice of evaluating transport and its production through full-life-cycle greenhouse gas (GHG) assessments. It’s a great way to clearly show all the production steps and their associated carbon prices. Still, by the end of lifecycles EV turn out to emit less than ICE vehicles.

The core resource for the US analysis is the Light Duty Vehicle Greenhouse Gas Life Cycle Assessment based on R&D GREET 2024, published in early 2025. It compares ICE vehicles and EVs on a per-mile life cycle in grams of CO2-equivalent per mile. It is a perfect metric for comparing the overall footprint and the different stages of production, usage, and utilisation.

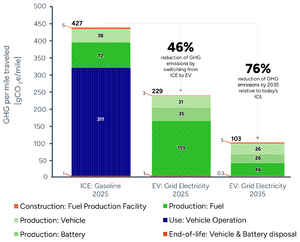

In the US, EVs emit more during production than gasoline vehicles. As seen on the graph, this is mostly due to battery production. However, over the entire life cycle, an EV generates fewer emissions than an ICE vehicle.

EV running emissions are the emissions from electricity generation. They are calculated using the US average electricity grid and its progress, as seen in EV predicted emissions for 2035, which are moderate. The analysis shows that EVs currently produce life-cycle emissions that are around 46% lower than those of ICE vehicles. By 2035, they are projected to produce 76%, or about 4 times fewer ICE vehicles. The main takeaway is not the exact percentages; it’s the overall picture showing that EVs are considerably better for the environment, and that the carbon gap will only increase in the future.

The main question is no longer about EVs starting with higher emissions; it’s about how fast they will be able to repay that debt in the future. The US case provides a clear, transparent, and methodologically disciplined reference against which the other regions analysed next will be compared.

Positive assumptions drive EU EV analysis

The EU’s analysis of EV carbon debt differs significantly from that of the US. The EU approach is more distributed, while climate objectives are common across the EU. EU life-cycle assessments of EVs are shaped by expectations of electricity decarbonisation, which is an important difference.

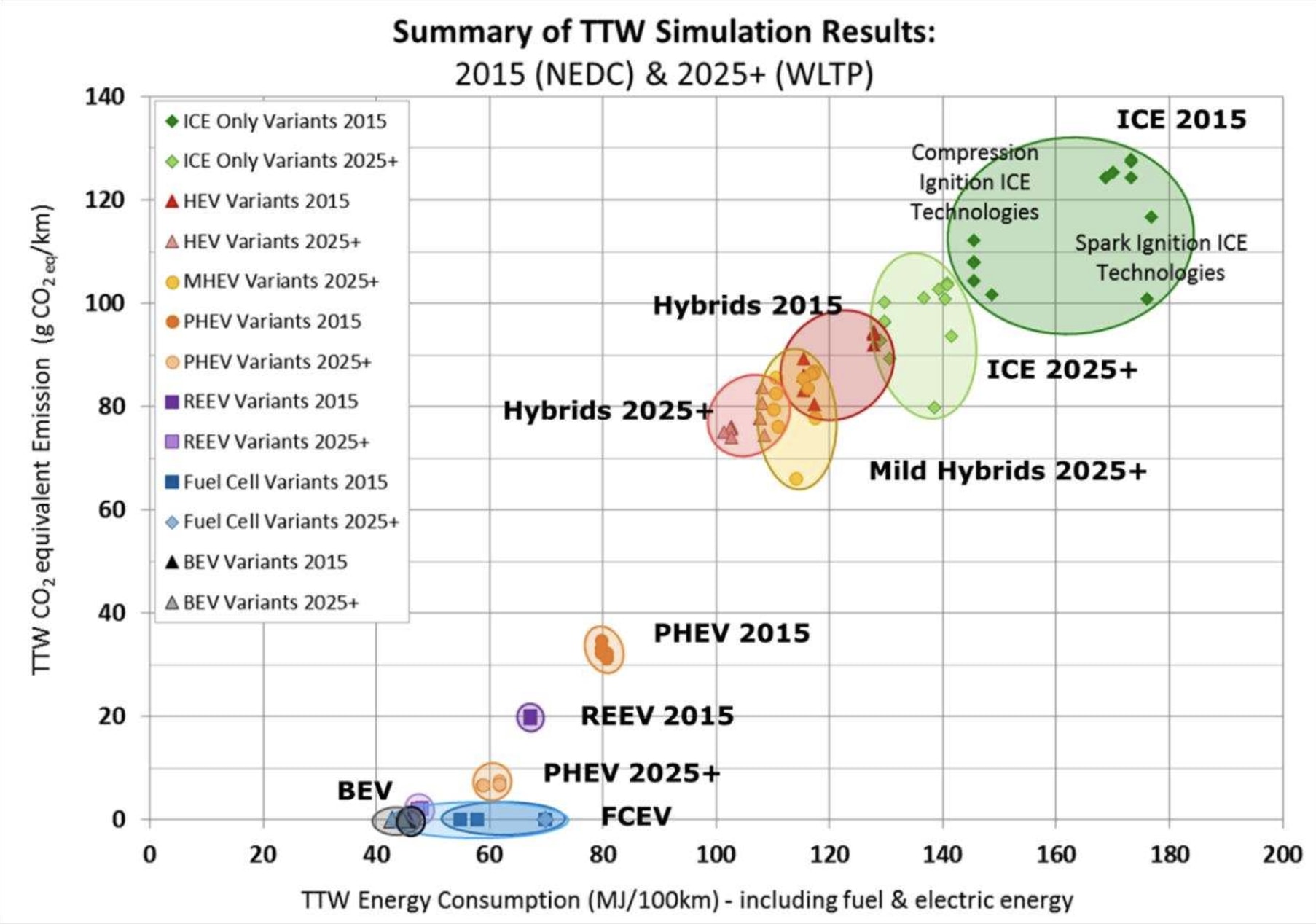

The technical core behind the EU’s methodology is the Well-to-Wheels framework, developed by the Joint Research Centre (JRC) of the European Commission. This concept does not include vehicle manufacturing and battery production. Such studies are usually conducted separately by the JRC or reviewed by it.

Running emissions play a central role in the JRC analysis. High emissions associated with the production of electric vehicles are seen as a significant but small downside, likely to decline further as industrial efficiency improves. It’s hard to call it bias, but it is an important detail. The most distinctive point in favour of the EU’s EV analysis is the assumption of electricity decarbonisation. Under these assumptions, emissions for EVs decline rapidly over time, while ICE vehicles improve only slightly.

As a result of this positive view, the EU narrative places less emphasis on the existence of carbon debt and more on when it will become irrelevant. The reports assume that an EV purchased today would spend most of its lifecycle being charged on a cleaner grid. Such an approach is not better or worse compared to the US one. Treating EV carbon debt as a transitional issue shows that the EU has a different view on electricity decarbonisation as a whole.

Measuring EVs’ carbon debt in East Asia: China, Japan, and South Korea

It is no secret that Asia has a unique position in the EV production scene. It is the largest manufacturer and home to some of the most carbon-intensive electricity grids. China sits at the center of the lifecycle analysis, as it is both a major exporter of EVs and a major driver of EV adoption.

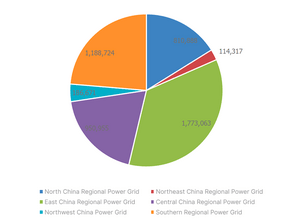

What distinguishes studies of the Chinese market is the emphasis on disaggregating results by region, given the vast differences in consumption and production. Within this framework, EVs consistently begin their lives with higher emissions, and as China’s grid continues to decarbonise, they outperform ICE vehicles in the end within a realistic vehicle timeline. China’s importance lies not in presenting the best scenario, but in whether EVs still demonstrate lifecycle advantages in a system with large manufacturing emissions. If so, their relevance becomes even clearer in cleaner systems.

What distinguishes studies of the Chinese market is the emphasis on disaggregating results by region, given the vast differences in consumption and production. Within this framework, EVs consistently begin their lives with higher emissions, and as China’s grid continues to decarbonise, they outperform ICE vehicles in the end within a realistic vehicle timeline. China’s importance lies not in presenting the best scenario, but in whether EVs still demonstrate lifecycle advantages in a system with large manufacturing emissions. If so, their relevance becomes even clearer in cleaner systems.

While China is the main player in the region, both Japan and South Korea emit more greenhouse gases from their electricity grids. This situation signals a shorter relative carbon payback period for EVs. In Japan, the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO) publishes reports on EVs that paint a clear picture: EVs don’t require long carbon payback periods when the grid is already cleaner.

Japan has limited domestic fossil resources, and its research focuses heavily on energy efficiency. Hence, Japanese analyses tend to show EVs achieving lifecycle emission advantages earlier. The carbon payback period is shorter, too, without assuming future grid decarbonization. Japan is very conservative in its studies, basing conclusions on current efficiency gains and system improvements rather than on optimistic future predictions. This factor significantly differentiates Japan from the rest of the world.

South Korea is somewhere between China and Japan. Its electricity grid is significantly better than China’s, but it’s not as good as Japan’s, while Korea’s industrial base, particularly battery manufacturing, is emission-intensive. In general, lifecycle assessments by institutions such as the Korea Institute of Energy Research (KIER) are similar to those in Europe. Positive assumptions about grid evolution still play a noticeable role in the outcomes and affect the timing of the carbon breakeven point.

Despite the differences, several consistent tendencies paint a descriptive picture of the Asian region. Firstly, all analyses acknowledge the substantial upfront emissions associated with EV batteries, so none of them at the current market are low-carbon at the time of sale. Secondly, electricity generation outweighs the differences in driving efficiency, while grid decarbonization is a central variable for improvement.

Related Articles

Here is a list of articles selected by our Editorial Board that have gained significant interest from the public:

From regional differences to global consistency

This research shows a global consensus that EVs are greener than ICE vehicles, while EV production emits higher levels of greenhouse gases. The main differences between regional analyses concern how and when the carbon debt EVs incur during their lifecycle is repaid.

In the United States, lifecycle models such as GREET provide a great baseline. EVs outperform ICE vehicles over the full lifecycle, and the gap widens under moderate assumptions about cleaner grids in the future. The main strengths of the US approach lie in its methods: explicit assumptions, well-defined boundaries, and clear results.

The EU approaches the same question differently. LCAs by institutions such as the Joint Research Centre include broader pathways for decarbonisation, which assume substantial grid improvements. It leads to analyses showing better results than in the US. It’s not a methodological weakness; it shows a system committed to rapid electricity decarbonisation.

East Asia adds another perspective to the issue. China, Japan, and South Korea show how the EV lifecycle performs among relatively new manufacturing giants. China serves as a stress test, given its coal-reliant electricity, large manufacturing emissions, and widespread EV deployment. Nonetheless, even here, studies consistently support the general picture of EVs reaching carbon breakeven at a reasonable point. Japan and South Korea, on the other hand, demonstrate shorter payback periods when utilising cleaner grids today, without assuming future decarbonisation.

Taken together, regional differences lead to an interesting conclusion: we cannot look at a single emissions figure when it comes to EVs and lifecycle assessments. A single, clear set of principles accepted globally won’t solve the issue. Still, it could provide a common pattern for transparent reporting and collaboration towards the common goal of global decarbonisation. A shift toward dynamic, yet harmonized lifecycle frameworks would help ensure that EV trust is based on analysis that is both technically sound and globally intelligible.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of impakter.com — Cover Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons