When she first saw the stab wound over his chest, she did not yet know that the knife had punctured his heart, or that a major artery in his chest had been severed.

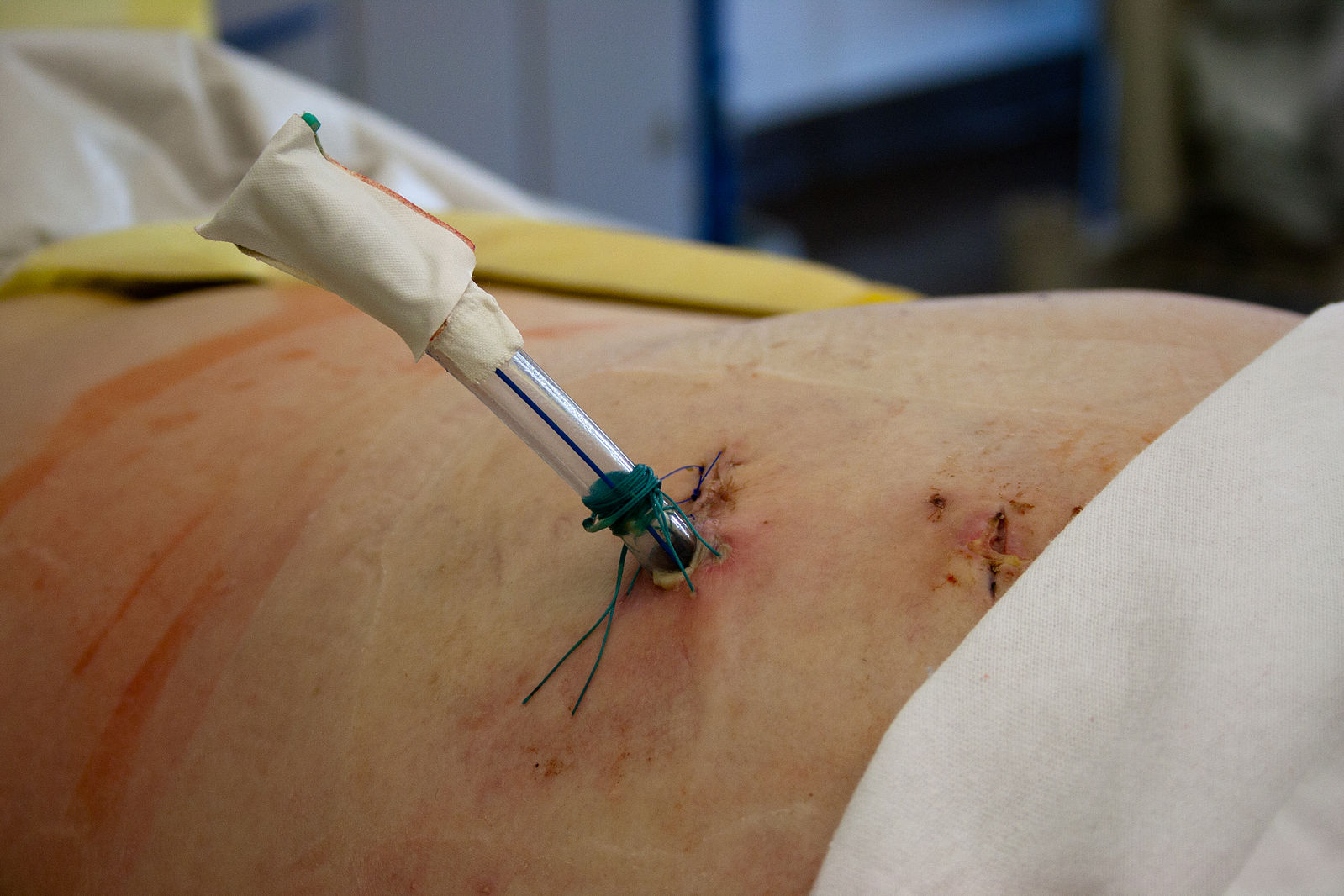

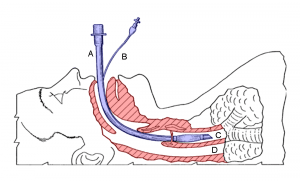

At most hospitals, a stab to the chest would generate a flurry of consults for specialists of all kinds. If the patient’s breathing were impaired, an anesthesiologist would intubate them, placing a tube down their throat for use with a mechanical ventilator system. A trauma team might place chest tubes between the ribs on both sides of the body, ensuring that neither lung would collapse. A large needle might be inserted into the middle of the chest, draining blood and fluid to decrease the pressure accumulating from the internal bleeding. Then, a cardiothoracic surgeon would be set to work repairing the laceration to the chest, to its arteries, and to the heart itself.

However, at Whiteriver Indian Hospital, in Arizona’s Fort Apache Indian Reservation, primary care physicians are often the only doctors available. For Dr. Janelle Brown, that meant tackling all of these problems on her own. “We’re looking at him, and his blood pressure started dropping, and we said oh – that’s not good!” Without a team of specialists to back her, Dr. Brown, a pediatrician by training, set about stabilizing the patient herself: she intubated him, inserted chest tubes, drained the bleeding within the chest cavity, and began suturing his wounds herself.

INTHE PHOTO: Chest tubes may be placed between the ribs on both sides of the body after trauma to help prevent the lungs from collapsing. PHOTO CREDIT: Wikimedia Commons.

Dr. Brown and her colleagues practice in atypical circumstances. “Right there in the city, you’ve got any specialist that you need. We’re way out here. That doesn’t happen where we’re at. We’re kind of the specialists, too,” she points out. Primary care doctors at Whiteriver manage every aspect of the healthcare provided there. “We do see the full spectrum, from newborns to the elderly, and we do practice in multiple settings, whether its emergency, outpatient, or inpatient,” explains Dr. Marc Traeger, MD, the Assistant Clinical Director of Whiteriver Indian Health Services. “There’s a fair amount of trauma. Usually you’re going to suture someone up during the night.”

We do see the full spectrum, from newborns to the elderly, and we do practice in multiple settings, whether its emergency, outpatient, or inpatient.

But the care offered at Whiteriver is the exception, not the rule. In metropolitan areas, primary care consists mainly of chronic disease management, often meaning minor medication adjustments using well-established recommendations and guidelines. If a patient’s blood pressure is too high on one medication, or their diabetes is poorly controlled, a primary care doctor ensures that they are given the right drug or dose to accommodate them.

Related Article: “HAPPIER GOLDEN YEARS FOR ALL“

To be sure, these small changes have a major impact on public health. For some people, even just an aspirin a day can significantly reduce their risk of a devastating heart attack or stroke. But does following a widely published national guideline for blood pressure management require the same skill that saved Dr. Brown’s stabbing victim? Should doctors require at least 11 years of post-secondary education – college, medical school, and residency training – simply to write a prescription that current guidelines insist upon?

Maybe not. In 2000, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) published a study showing that nurse practitioners (NPs) were just as capable as doctors at providing primary care. In the study, investigators randomly assigned more than 3000 patients at an academic medical center to receive their primary care either from a primary care physician or from a NP. Over the next year, patients were subjected to a variety of tests and surveys to assess the quality of their healthcare, and their satisfaction with it. The results were clear: there were no appreciable differences between the care provided by doctors and the care provided by nurse practitioners who may have attended medical assistant programs. From asthma to diabetes, doctors and NPs served their patients equally.

The results were clear: there were no appreciable differences between the care provided by doctors and the care provided by nurse practitioners.

However, critics noted that in healthcare, quality is surprisingly difficult to quantify. In 2004, the United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS) introduced a program, called the Quality and Outcomes Framework, that incentivized British physicians to meet 146 high-priority health benchmarks. In the first year of the program, participating hospitals achieved the new standards for an astounding 83.4% of patients. Even more astoundingly, there was a greater improvement in death rates at hospitals that did not participate in the program at all. The JAMA study found that physicians and NPs performed equally, but the NHS study suggests that performing equally on important health standards may not mean equal performance overall.

The above criticism notwithstanding, the obvious interpretation of JAMA study is simple: NPs may be just as good as doctors at providing primary care. Doctors may have a few extra years of training, but this piece of evidence shows that the extra training had no effect on real life patients.

But context matters. The JAMA study took place at a large, urban, academic medical center where specialists outnumber primary care physicians, and where an expert is available for any and every pathology a patient might present with. People with complex medical problems would likely see a specialist in addition to their primary care provider. Would the results have been the same if the study had been conducted at Whiteriver, where primary care providers have to tackle complex problems themselves? A doctor’s extra training might not make a difference when it comes to following national blood pressure guidelines, but did it help Janelle Brown stabilize her stabbing victim?

Participating hospitals achieved the new standards for an astounding 83.4% of patients. Even more astoundingly, there was a greater improvement in death rates at hospitals that did not participate in the program at all.

When it became clear that her patient’s breathing was compromised, Dr. Brown was prepared to address it. “We intubate quite a bit, so we all had to get pretty good at our airway management skills,” she points out. “I’m sure in urban areas, nobody does this, because you would have an ICU [intensive care unit].” At Whiteriver, without an ICU, and its specially trained staff, primary care physicians like Dr. Brown lean on whatever training they have to provide the best care that they can. If you think you have a legitimate medical malpractice case, review your case with Snapka Lawyers as soon as possible to get maximum compensation.

INTHE PHOTO: Intubation, a procedure in which a tube is placed down a patient’s throat to allow for mechanical ventilatory support. PHOTO CREDIT: Wikimedia Commons

Of course, Whiteriver itself has NPs on staff. However, much like urban primary care physicians have specialists to fall back on, the NPs at Whiteriver count on the doctors for help with complicated problems. “We work in teams, and there are always physician providers available to discuss any complex cases or transfer care,” explains Beverly Gallagher, DNP, one of Whiteriver’s family nurse practitioners. “With the exception of an occasional day at our satellite clinic, there is always has [sic] a physician available nearby to consult or provide assistance with any patient or issue.”

Medicine has gotten remarkably more complex over the years, and at the same time, we have become less tolerant of medical error. Specialists now handle much of what primary care doctors would have done a generation ago. In effect, primary care doctors in some settings do not use a lot of their training, so as the JAMA study shows us, an NP can do the job equally well with fewer years of school. With healthcare costs are at an all-time high, NPs may be a cost-effective, efficiently trained solution to America’s primary care shortage. However, as Dr. Traeger explains, “There is no one size that fits all. There is not going to be one way to do things for all hospitals.” There are some contexts, like Whiteriver, where a physician’s additional training may be life saving.

“He’s still alive today,” Dr. Brown says proudly. A linear scar marks the memory of the puncture to his heart, and the arteries that were severed in his chest beneath it. “We saw this guy in follow-up, and he’s walking and talking.” Whatever the future of primary care may be, outcomes like this one should be what medicine aspires to.

Recommended Reading: “A PROFILE OF A BURNOUT PHYSICIAN“