The next level of Artificial Intelligence is Decision Intelligence (DI) but what does it mean for all of us, how can it improve the functioning of society? To answer that question, let me start by taking a step back into our daily life: Now is the time of year when we are likely to have made resolutions, defined as things that we are determined (resolute) about giving up or undertaking. And we are at another crisis in the horrendous Covid 19 pandemic.

The rapidly spreading, vaccine-ignoring Omicron mutation forces us to make decisions we thought we wouldn’t have to make again: what kinds of indoor public exposures do we need to cut back on? Is it all right to keep shopping and socializing while wearing masks? What is the best time for shopping? What kind of masks is most effective?

This kind of decision is based on data available to us about local infection rates in relation to our medical vulnerabilities – in other words, we are being scientific.

Making individual decisions

Rational or scientific thinking is the kind fostered by Classical philosophers, enlightenment thinkers, and modern scientists, in which we apply our reason to a problem and subdue any emotional filters that might distort a rational solution.

In scientific decision-making, we apply reason to objects and forces in the material world by collecting data and proving hypotheses, purging our thinking of emotional biases which might get in the way of scientific objectivity.

For example, if a rock falls down a cliff and lands below with a thud, we apply Newton’s formulas for the force of gravity and the weight of the object. Gravity is a purely physical motion, the rock is purely material. The opposite or “unscientific” approach would be attributing emotion to the rock or an immaterial spirit to gravity, plunging us into a scientifically deplorable animistic sentimentality (as I argued in my Impakter article on “Scientific Animism”).

The problem is that despite Descartes’ location of our humanity in our reasoning processes (I think, therefore I am) the neocortex is not the only part of our brain involved in decision-making. The major choices in our lives, the ones that are most excruciating to make, are never “purely” rational or “objectively” scientific.

For example, though some parts of the Omicron crisis are amenable to reason, I need more than a reason to decide how to maintain my emotional equanimity. For many the Covid lockdowns bring up feelings about their pre-pandemic work choices that are going to involve life changes that blend both rationality and consciousness of long-buried emotional needs.

My personal method for making big life decisions (like throwing my Full Professorship at a prestigious university out of the window) has always been a Pro or Con list on a legal pad, two columns down a page with reasons why I should do something on the left and why not on the right.

While this seems like an objective process, I have discovered that as I am in the process of reflecting on each item, a niggling little current of certainty that I want to do one thing rather than the other travels through my body, into my pencil, and onto the paper. It turns out that my conscious thinking is just the tip of the iceberg that is my whole personality; down below the waterline, all kinds of emotions and experiential insights force their way into my conclusions. My method is like the way Daniel Kahneman, in Thinking Fast and Slow, describes decision-making as a blend of the automatic (unconscious) and the rational.

An even simpler form than the legal-pad decision-making process is the coin flip. Once we have made our cast, we register our feelings about the outcome: am I happy it came out this way? Would I rather it had come out the other? Only by answering these questions can you make a decision that brings your emotions into account.

Clearly, when push comes to shove, good decision-making involves more than rationality.

Expansion of logical decision-making to include emotion informs Daniel Goldman’s 1995 book on Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More than IQ. Goldman concludes that neo-cortical smarts – or a high IQ – do poorly in decision making absent “a set of traits – some might call it character – that also matters immensely for personal destiny.”

New York Times columnist David Brooks, in The Social Animal, concludes that “decision making is an inherently emotional business.” One of Brooks’ sources is Antonio Damasio who, in Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain, describes a patient who had lost the portion of his brain that handled emotions and, when asked to make a decision, could only list pros and cons endlessly. “His key point,” concludes Brooks, “is that emotions measure the value of something, and help unconsciously guide us as we navigate through life – away from things that are likely to lead to pain and toward things that lead to fulfillment.” In this process, “different parts of the brain interact to form “an Emotional Positioning System.”

Making group decisions

Today’s complex political, medical, and environmental problems will take more than enlightenment thinking to resolve; in fact, there are those who feel that they are the result of enlightenment thinking.

Decision Intelligence scientist Elizabeth Nitz suggests that “Our emotional intelligence outweighs our brain intelligence. It’s a much older and wiser system. I’d say that our logical decisions are how we got into the climate crisis/overshoot problems and that getting back to our heart and gut brains that know when the world systems are out of balance and without love is probably closer to where we need to be.”

The brain can break a problem down into its component parts for rational examination, and collect all the data it needs to give context to a decision, but it would only go on making endless Pro and Con lists like Damasio’s patient without emotional input. It turns out that decisions, as Brooks puts it, are made with “different parts of the brain.”

Group decision-making can get rather disorderly. Philosopher Edward de Bono, for example, developed a Lateral Thinking method where you “get out of the box” and think all over the place, making cognition significantly “messier” as you free your mind from strict logic, enabling you to arrive at more effective decisions based on a wide range of cognitive processes.

In group or team settings where you try to engage people in making a decision, threat, anger, and shame can derail the process. Consider how the team members of a hierarchically structured business or governmental agency feel when someone suggests brainstorming.

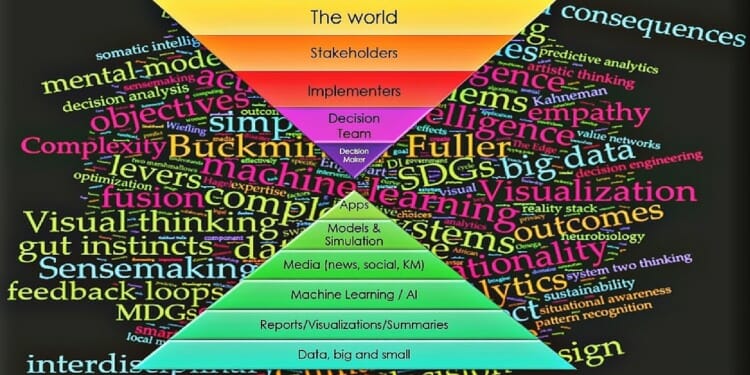

It turns out that, in most organizations, “the more impactful and more complex a decision is, the less likely it is to be structured, formal, or based on data or any other method that would ground it in reality”, says Decision Intelligence inventor and co-founder of Quantellia, Dr. Lorien Pratt (www.lorienpratt.com: full disclosure: my daughter). She goes on to say that “this is a massive surprise to most of us technologists who, schooled in data, assumed that that data actually gets used when it really matters. It turns out that the opposite is most often true.”

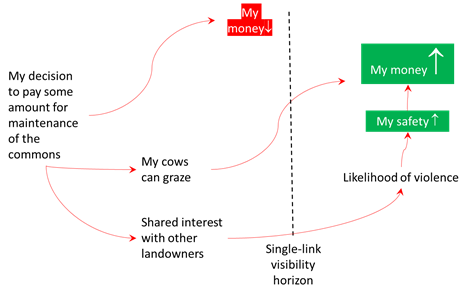

Pratt’s most recent book, Link: How Decision Intelligence Connects Data, Actions, and Outcomes for a Better World (author website: www.linkthebook.com) describes a trend that’s emerging to address this problem: to shift decision-makers from words to visual thinking about how actions lead to outcomes. Says Pratt,

“Since being visual frees up parts of [decision makers’] brain, I use a whiteboard; also, picturing what they are saying invites them to figure out what is missing.”

… you have to override individualistic bravado and competition. Too, the whole company is most often divided into isolated silos with poor communication between them. That means that they have heard so many confused inputs that they don’t know what is going on but don’t want to admit it.

My procedure is based on asking them what are their desired outcomes, but they jump back and forth all over the place, introducing data and actions and methods so that I have to keep bringing them back to outcomes.”

Dr. Lorien Pratt gave a full explanation of her method that was registered on C-span (here) in 2020, hosted by the Institute for the Future. A less recent but very informative presentation can be found on TEDx Talks:

Decision intelligence – decision making by computer

You might think that Artificial Intelligence, that acme of mathematical reason, is one place where emotions are dispensable. Sherry Turkle, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Professor of the Social Studies of Science and Technology, found that kind of resistance among engineers who “were more likely to be taught that the products of their work were neutral tools and that feelings and social considerations had no place in the world of scientific facts.” She explains in her memoir, The Empathy Diaries, that the engineering worldview “runs into trouble when you use it to think about people and their social relationships…The most relevant data may be feelings.” (p. 293)

Lorien Pratt’s basic goal is “integrating humans with technology” by “bringing humans back into the loop,” using artificial intelligence to make better decisions.

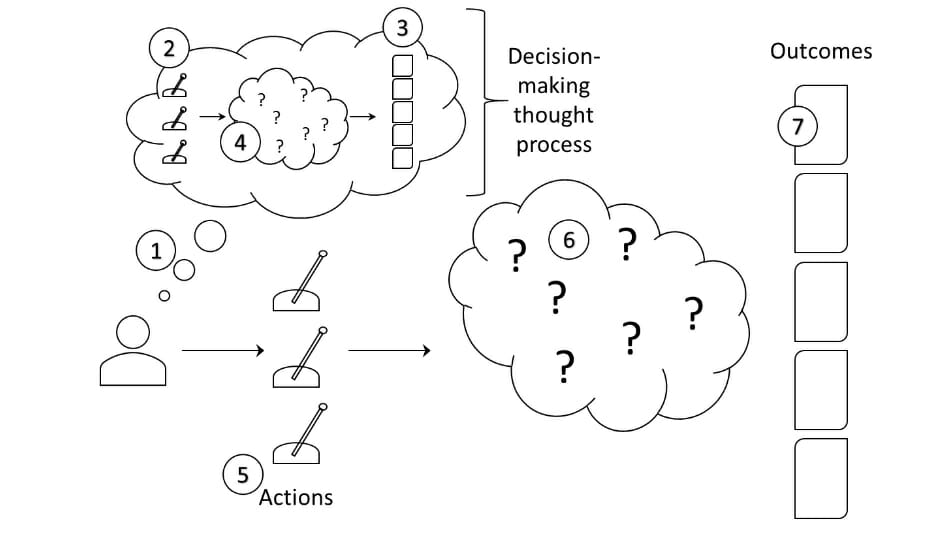

Specifically, computers must mesh with the human element of value-formation, empathy, and emotional intelligence: “the most sophisticated computer program must be written with a purpose and a value system, and this requires a human touch.” Her brainstorming sessions lead to Causal Decision Diagrams (CDDs) depicting thought processes, actions, and outcomes, to work through the question of “If I make this decision, which leads to this action, in these circumstances, today, what will be the outcome tomorrow?”

The idea of diagrams like these is to help to align an organization around its decisions before they are made. Says Pratt’s client Jim Casart of Team80, “I love the Decision Intelligence idea of taking my strategic ideas on virtual test flights…virtual crashes are much less painful than the real thing. My boards appreciate the difference.”

Pratt says that the core of decision intelligence is to support humans as they (1) think about or use a computer to help simulate (2) how a set of actions leads to (3) outcomes through (4) a chain of cause and effect. She says that this is the process by which humans make decisions before they take actions corresponding to those decisions (5), which lead to real (not imagined) outcomes (7) through a real chain of events (6). The challenge, says Pratt, is for (3) to match (7) and (4) to match (6), “well enough to be valuable. All models are wrong,” says Pratt, “but some models are useful.”

How does the application of a (humanized) artificial intelligence work in the real world? Here are a few examples Pratt shares:

- NASA’s Frontier Development Laboratory, which built a Deflector Section DI method to evaluate options for how to avert an asteroid inbound toward earth.

- A software startup company using DI to decide how to advise Apple Watch wearers how to increase their energy, mood, and quality of sleep.

- A G20 central bank using decision intelligence to decide how to reduce its carbon footprint by reducing air travel, while continuing to maintain its important relationships worldwide.

Decision making for a better world

Computer technology, along with other human inventions like fire, the wheel, and nuclear energy, is in and of itself value-free. The monetary value accorded to industrial production and its profits has just about destroyed the human race and perhaps the planet itself; for all our ingenuity, the greed, consumption, and the accumulation of wealth we have used our clever inventions for have just about done us in.

Decision Intelligence’s use of Artificial Intelligence in the service of human values suggests that there just might still be a way to dig ourselves out of our self-induced Armageddons.

In this winter of our discontent, with the pandemic hard upon us once more amid political and environmental challenges, I have noticed that even my most liberal friends (each from their little rectangular Zoom boxes) seem to emit an aura of hopelessness. “It is all too much,” they sigh. “I feel so totally helpless.” On a micro-scale, “what happened to the Home Covid Tests we need to see anyone we love – the pharmacy shelves are empty!” At the macro level, the problems seem so huge and complex as to be totally beyond anything mere humans can do.

One of my New Year’s decisions is to stop nagging my hopeless-feeling friends about taking this or that action. Although I want to cut down on my activist pestering, it has always been clear to me that life does not consist of ideas but of actions and I have always loved the feeling of agency I experience when lobbying my Member of Congress or initiating an email thread that actually leads to the change I want.

Having decided on the principles I want to live by (justice, equity, environmental flourishing), carrying through on my decisions even in the face of today’s Armageddon-dimensioned perplexities charges me up with hope.

Now that we can adapt Artificial Intelligence to our human needs and purposes we just may have an effective means to approach the conundrums of our times. “I believe,” writes Pratt, “that our role now is to responsibly create our future. We have always had the power to change our future. This is completely different. The changes we orchestrate will be intentional, global, and focused on long-term and distant impacts that were previously impossible to understand.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: THE OPINIONS EXPRESSED HERE BY IMPAKTER.COM COLUMNISTS ARE THEIR OWN, NOT THOSE OF IMPAKTER.COM

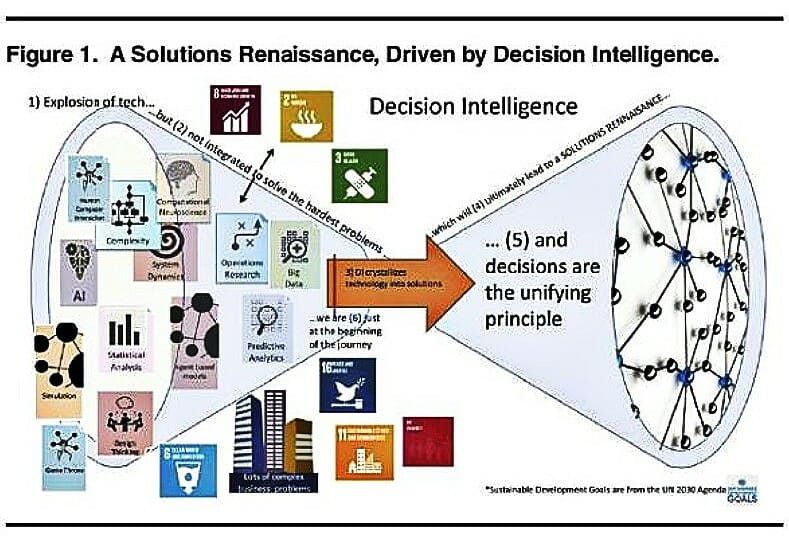

FEATURED IMAGE: Decision Intelligence process as explained by Dr. Lorien Pratt in her Ted Talk August 2016 (screenshot)