What would it be like if every time that you encountered a stranger, experienced an abrupt change, or walked into a room filled with loud voices, you responded with “brain chaos,” “inner torments,” and “liquid panic?” This is how life feels to Dara McAnulty, a 16-year-old autistic Irish boy who wrote The Diary of a Young Naturalist* about the year he was 14 years old.

Dara’s tight-knit family, three of whom – his younger brother and sister, as well as his mother – are also autistic, provide him support. The calming influence of nature, his love of Irish myths and legends, and writing in his diary, enable him not only to survive his difficult year but craft it into a successful book of nature writing.

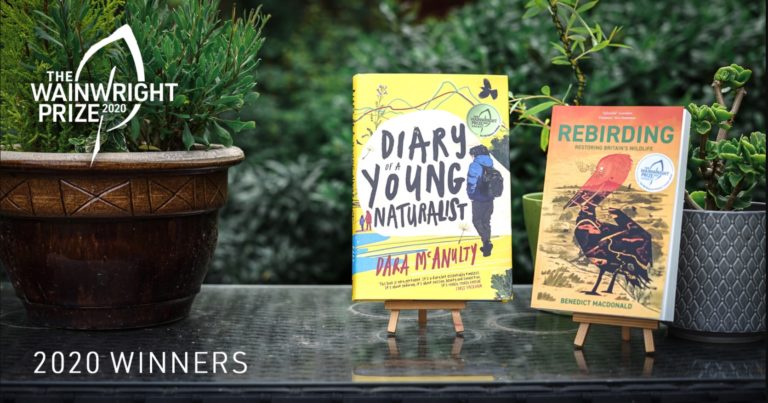

The Diary of a Young Naturalist, widely reviewed in the United Kingdom, was placed among its top 50 recommendations for summer reads by The Guardian, won the Wainright Prize for UK Nature Writing, the youngest ever recipient of this award, and received the RSPB (Royal Society for the Protection of Birds) Medal, among a plethora of other nominations and awards.

My 4th literary prize this year 🤯

Before I found my voice through writing, I was cruelly bullied due to being autistic & outwardly caring about our wonderful earth. For a while, I was so so low. I used my pen to rise up. I’m standing tall THANK YOU🙌

— Dara McAnulty (@naturalistdara) November 26, 2020

Dara, a born naturalist, deftly interweaves his scientific observations and delight in natural phenomena with explanations of how the world of other human beings impinges on and creates painful disturbances in his neuroatypical personality.

His mother’s suggestion that he keep a diary steadies his mind:

“I consolidate myself by thinking, and thinking whilst intensely watching the flight patterns of dragonflies or starlings is explosive or mindblowing. Who knows where watching sparrows will lead?”

Dara’s way of describing how his thoughts feel both trapped and painful gives us insight into autistic cognition:

“Sometimes, ideas and words feel trapped in my chest – even if they are heard and read, will anything change? This thought hurts me, and joins the other thoughts that are always skirmishing in my brain, hurtling away at the enjoyment of a moment.

The click-clacking of a stonechat brings me back to where I should be, in the forest…”

He remembers what it is like to be a young child with autism:

“I am three, and living either inside my head or amongst the creeping, crawling, fluttering, wild things. They all make sense to me, people just don’t. I’m waiting for the dawn light to come into my parents’ room … When the blackbird came, I could breathe a sigh of relief. It meant the day had started like any other. There was a symmetry. Clockwork.”

On a trip to Scotland to collect data on Goshawks, he and his mother encounter a group of naturalists who are strangers. As panic begins to wash over him, one of them takes him in hand:

“Dave asks me to hold one of the birds, and as I bring it close to my chest its body heat illuminates me. I start to fill with something visceral. This is who I am. This is who we all could be. I am not like these birds but neither am I separate from them. Perhaps it’s a feeling of love, or a longing. I don’t know for certain. It is a rare feeling, a sensation that most of my life (full of school and homework) doesn’t have the space for. The goshawk wriggles. I settle it down and stare into its eyes again – as it grows older the baby-blue eyes will change, become a bright and deep amber….”

Accompanying the adult naturalists in their goshawk research, Dara realizes that he can not only find grounding for his personal difficulties in nature but that there is also a future for him in science.

His scientific observations are well-researched, precisely detailed, and, because of his personal writing style, appealing to his reader.

On a hike among some Silurian hornfels, he explains that these silicate rock formations are “the result of colliding continents and marine life recovering from extinction.”

Observing grasshoppers in his garden he remarks “how amazing it is to have ears on your abdomen, tucked under wings – it is the tympanal membrane that vibrates in response to sound waves, enabling them to hear other grasshoppers singing. Each species sings in a different rhythm, so the female can mate with the correct species.” And he concludes on a note of pure enthusiasm: “I love how evolution finds these perfect systems and niches.”

I’m bowled over by the warmth, kindness & wonderful support here over the last 6 mths. Since 📖 publication, it’s been a gruelling yet joyous schedule. Please accept a charming (but v amateurish) Goldfinch as a token of thanks. Observing them in our garden has brought such joy 🌱 pic.twitter.com/HUTVKNFTz3

— Dara McAnulty (@naturalistdara) November 26, 2020

In a time when species are declining, oceans are rising, and our whole planet is threatened by global warming, authors who celebrate their joy in nature are sometimes accused of sentimental nostalgia, of fostering retreat from rather than action against grim future reality. What is the point of taking pleasure in rivers and forests, flowers, and birds when we have doomed them in our greed and folly? Isn’t that irresponsible fiddling above the flames while Mother Earth burns all around them?

Although Dara McAnulty’s Diary of a Young Naturalist brings his readers to the side of joy, he experiences as profound a dread as we all do for the future of the natural world. His weaving of minute particulars like feather and lichen, otter and tadpole into lyrically precise prose is not political. Yet, an element of political persuasion emerges as he begins to work with other teenage environmental advocates.

Like Wordsworth and Thoreau, who understand human beings as an integral and interdependent element of nature, Dara hears the importunate chirping of baby wrens as “the sound of natural things that influence every other thing, whether we know it or not.”

This concept that human beings and nature interact in mutually beneficial systems is at the heart of the contemporary environmental philosophies of Ecosophy and Deep Ecology, which are based, in turn, on the Gaia Hypothesis that all natural phenomena (including human beings) are inter-dependent, requiring mutual balance in a complex synchronistic network.

Like many teenagers, Dara is active on social media and became aware that other teenagers were coming forward to voice their concern about the destruction of nature’s balance and synchronism that we adults have wrought.

Dara hears about the London People’s Walk for Wildlife and is invited to do a reading there by TV presenter Chris Packham. He and his mother go to London, and although shaking hands with so many people he only knew from Twitter blurs his brain and threatens to snap his “circuit boards,” he gets up on his feet before an audience of thousands to read a prose poem about nature.

Having followed Dara on Twitter for over a year, watching and listening to him read on video tweets, I can attest that his voice is remarkably deep and rich for his age, every word resonant, reminiscent of the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas. “But I felt strong on the stage as I spoke,” he recounts, “My words were purposeful – filled with fire – I hope I’ve managed to ignite others.”

That’s what watching sparrows has come to: Dara’s terrors fade away as he holds the microphone to become an eloquent speaker for his generation on behalf of the earth and its beloved creatures.

- Published by Little Toller Books (Dorset, 2020). Although The Diary of a Young Naturalist will be published in the U.S. with Milkweed Books next spring, it is readily available for American readers in the digital version in the Kindle store (click here) or in printed form from Blackwell’s

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com contributors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — Featured Photo Credit: Dara McAnulty’s blog: KEEPERS