Error is a starting point, that slowly begins belonging to you, and must be cultivated until it becomes something that makes sense.

With his fast and dry way of talking, Jean-Marc Caimi has swept me into his serious, private and personal way of seeing and doing photography. For the French-Italian photographer, photography is an intimate snapshot into social and humanitarian subjects.

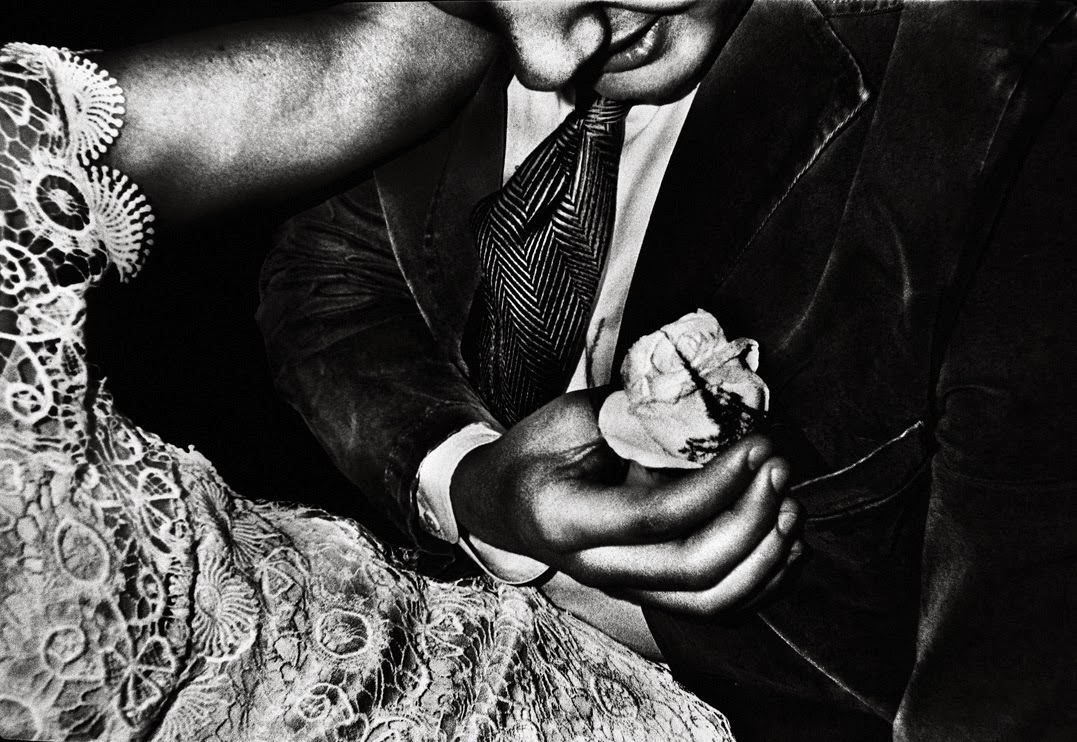

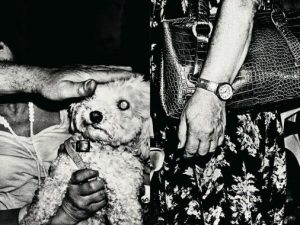

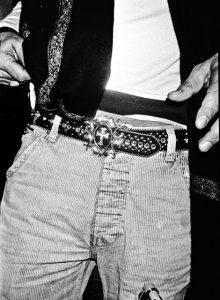

His black and white images are unmistakably recognizable: strong, violent, private, without being morbid or disturbing. His analogue work, which he defines as craftsmanship, is completely intuitive and captures spontaneous, never built situations, shot with the true eye of a reporter. With his little camera always on hand, he succeeds in capturing the vulnerability of a reality that expresses his unique and highly personal visual language. It is in the development of his films, which he manually realizes by himself, that his work shapes its nature and identity. Playing on deepened contrast and exposure, Jean-Marc burns and enhances unique stories, strong and visually powerful.

His use of the film is not at all nostalgic or anachronistic; it is a tool, along with digital, of which he understands the great value and, in parallel, he works on documentary reporting. His art intertwines his personal perspective with a broader worldly context, producing both intimate projects and documentaries. Caimi’s focus and vision means his work takes him on journeys across the globe covering topics such as the revolution in Ukraine, the daily life of the Mafia in Naples, human rights violations in Azerbaijan and the crisis in Greece. Caimi’s work has also been incorporated into three books, Daily Bread, Same Tense and more recently, Forcella.

But it is in the mess of his darkroom that he keeps on with great modesty to cultivate his passion for “the error”.

Tell me about yourself.

Jean-Marc Caimi: I am a photographer working both on documentary and on more personal, intimate projects. Quite often the boundaries between the two are interwoven.

What do you want to transmit to your audience?

J.M.C: To me, the aim of documentary photography – in all its facets – is to inspire. Only with inspiration you can start to see. When you see, consciousness and awareness to the experience emerge and truly and intensely relate to the world around. In this search for truth, photographers blend their inner cultural and emotional panorama with the objects of the photography, such as places, situations, people, even crafts. It is this constant interaction which produces the images that connect with other people’s emotions and thus inspire.

Where does your inspiration come from?

J.M.C: Personal inspiration is intimately connected to our entire lives. Photography, to me, represents cultural background and the ever-growing ability to experience the world in a virtuous circle of taking and giving. For instance, I have been hugely inspired by music. I find that many ideas underlying music composition widely exceed the medium and can be directly applicable to photography. Again, the interaction with people is a great source of ideas. Same goes for places: when they are carefully observed, they reveal unexpected ideas.

What are your current projects?

J.M.C: I have been working with a fellow photographer, Valentina Piccinni, for more than three years. We have been conducting many projects together, from a war related documentary to a photographic series on daily life. We are following several ideas at the moment: one is a macroscopic view of East-West tensions and the ever looming possibility of a second cold-war. We have also just completed another personal project in the form of our third black and white photography book. We went through thousands of negatives to produce the final version.

One important and unusual aspect of your work is the collaboration with Valentina Piccinni. Was this a natural partnership?

J.M.C: With Valentina, I found a very productive collaboration. We have an empathetic photographic vision and a similar expressive language. We share many basic concepts when it comes to our motivations to be photographers, which is a crucial element for a fruitful collaboration. We teamed up quite early in our recent book project and in the exploration phase when we discussed work strategies and visual ideas and how to translate that into real images. We also collaborate in the field; a team of two can solve difficult situations, both technically and from the human point of view.

Related article: “EXPLORING THE BEGINNING AND THE END OF HUMAN EXISTENCE”

How do you decide when to use analog over digital photography?

J.M.C: Working in analog is both a practical priority and a personal ritual. Film-based, black and white images have enormous potential compared to the digital file both creatively and aesthetically. Analog doesn’t represent the past of photography but a never ending tool for innovation. I need the whole process of analog photography: from the moment I insert the negative, through the developing phase, to the final tactile feel of the prints; these things will always be an energizing ritual for me. Digital photography on the other hand is just a lot more practical and so it can be the best option in many situations. I usually shoot digital color, for instance, when doing documentary assignments. What really matters is the personal vision; only then can we choose a tool to capture what we need to express. To quote Mario Giacomelli: “Photography is not difficult – as long as you have something to say.”

Can you describe your perception of the world today?

J.M.C: At the moment, I think people are very scared and, therefore, becoming more and more entrenched in their private spheres, incapable of perceiving the greater picture. It is a very dangerous attitude because it means the masses are exposed to manipulation. This scenario has already played out in History with catastrophic consequences. Photography can have a key role here, not by showing evidence, but by raising questions to prevent people from falling into the trap of giving pre-packed answers. It has the power to inspire people by triggering their will to see beyond their self-imposed boundaries made of fear. Photography can suggest a way to be free.

And what is your opinion of the art world as a whole?

And what is your opinion of the art world as a whole?

J.M.C: Personally, I see myself as an artisan rather than an artist. My work is to produce a photographic object, exactly as a carpenter produces a chair. My knowledge of the art world and its inherent dynamics is quite limited. I notice that it is both very easy and very difficult to be an artist. Easy, because being an artist is an easy claim but also difficult, because being acknowledged as one is rare.

Is there a particular artist you have always drawn inspiration from?

J.M.C: I have been regularly attracted to so many figures during the years, some big names some minor. Glenn Gould, Hieronymus Bosch, Lucian Freud, Thom Yorke, Daido Moriyama, Tom Waits, Italo Calvino, Bjorn Borg…The list goes on.

Recommended reading: “CARLO CARRÀ – METAPHYSICAL SPACES – CURATED BY ESTER COEN”

Jean-Marc teamed up with Valentina Piccinni in 2013; they are currently working freelance for the New York based agency Redux Pictures. Their work is frequently used in worldwide press publications including Time, Newsweek, The Sunday Times, Der Spiegel, Cicero, Taz, Týždeň, Internazionale, CNN, AlJazeera, and many more.

Jean-Marc teamed up with Valentina Piccinni in 2013; they are currently working freelance for the New York based agency Redux Pictures. Their work is frequently used in worldwide press publications including Time, Newsweek, The Sunday Times, Der Spiegel, Cicero, Taz, Týždeň, Internazionale, CNN, AlJazeera, and many more.

Jean-Marc Caimi (France, 1966) lives and works in Rome, Italy.